Gravity

Gravity

By LaurentMT

Posted August 27, 2018

This is post 1 of 3 in a series

“Law I: Every UTXO persists in its state, except insofar as it is compelled to change its state by force impressed.” — Isaac Newton, Principia 2.0

Newton diffracting an UTXO with payment batching

Newton diffracting an UTXO with payment batching

In the last years, a lot has been written about the “huge waste of energy” resulting from Bitcoin’s Proof of Work (PoW). In this series of four posts, we’re going to challenge this widespread opinion by questioning the main metrics used to highlight the alleged increasing inefficiency of Bitcoin’s PoW.

In this first part, we’ll first discuss the main utility of PoW in the Bitcoin protocol. Then, after a reminder of two important properties of Bitcoin’s PoW, we’ll define a mathematical formalization of this utility (Bitcoin.Days Secured) and we’ll use it to define two new metrics (Unit Cost and Average Cost). At last, we’ll check what these metrics can teach us about the evolution of the efficiency of Bitcoin’s PoW over time.

Prologue: The Cryptopocalypse is coming

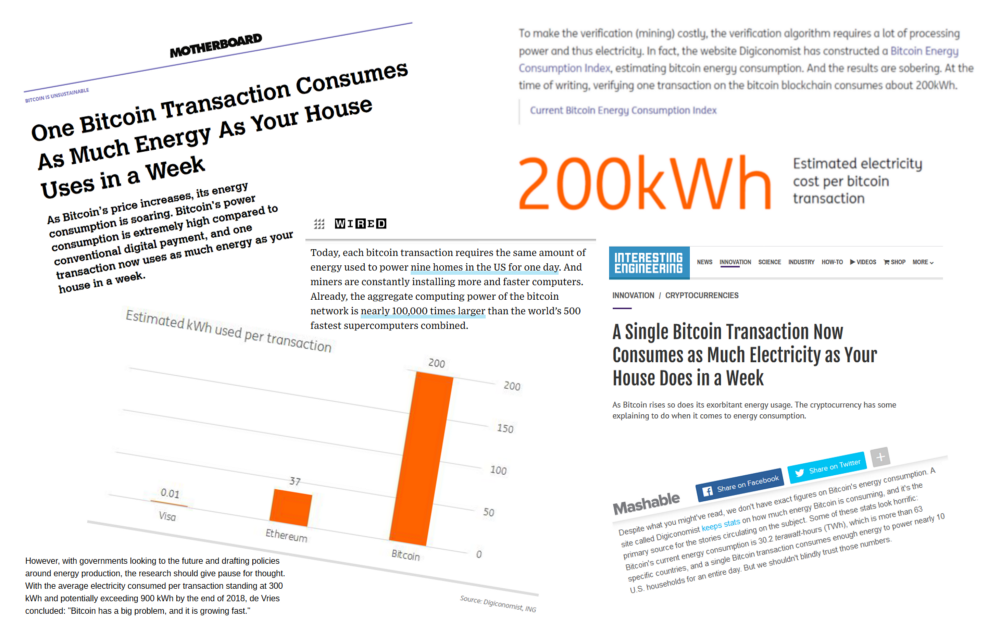

The news was on all the media a few months ago. The cryptopocalypse is coming. Bitcoin’s Proof of Work (PoW) is so bad that it’s going to destroy the world in 2020…

Pot pourri

Pot pourri

Reading a bit further, you may have noticed that most of these articles were based on the results of an analysis provided by Alex De Vries, a “financial economist and blockchain specialist” working for PWC Netherlands and author of the site Digiconomist.

I must confess that I have mixed feelings about this study. My issue with De Vries’s work isn’t the estimated electricity consumption (this part has already received its “fair share” of criticisms) but the repeated use of a specific metrics: the electricity consumption per transaction. Don’t get me wrong. In terms of communication, this metrics is pure genius especially for those eager to make a point against Bitcoin’s PoW. The figure seems so outrageously disproportionate that it prevents any further discussion. The problem is that this metrics is fundamentally wrong. For several reasons.

First, it mistakes the number of transactions with the number of payments. But let’s be fair, that doesn’t radically change the actual figure. So let’s forget about that.

The second issue is that the figure is often published without specifying that there’s no correlation between the electricity consumed and the number of transactions; or to put it differently it’s almost never acknowledged that the electricity consumed is a fixed cost with regards to the number of transactions (and not a variable cost). With technical solutions like payment channels or the Lightning Network, it’s obvious that we can radically decrease the value of this metrics as low as we want. That highlights 2 points: the metrics is easily “abusable” and it doesn’t tell us anything about future performances of Bitcoin’s PoW.

The last problem with this metrics is that it promotes a flawed understanding of the utility of Bitcoin’s PoW. It’s no surprise that it has gained a lot of traction in a period of “Blockchain, not Bitcoin” frenzy but we should make our best to promote rational thinking instead of an endless squabbling based on emotional reactions.

So. Arrived at this point, we’re facing the obvious question…

What is the utility of Bitcoin’s PoW ?

The “Gold Mining” theory

A first theory is that the main utility of the PoW algorithm is the issuance of new coins. Paul Sztorc has written a good post on the subject. This theory is seducing because it seems consistent with the widespread metaphor of gold mining used for explaining the mechanism.

I have sympathy for this theory and I think that it captures an important aspect of the protocol but for this series of articles, I’m not going to consider the issuance of new coins as the main function of the PoW algorithm. To support this choice, I’ll refer to this observation: while it’s expected that the emission of new coins stops around 2140, it’s not planned that Bitcoin mining stops at the same date. That suggests that PoW plays another important role in Bitcoin.

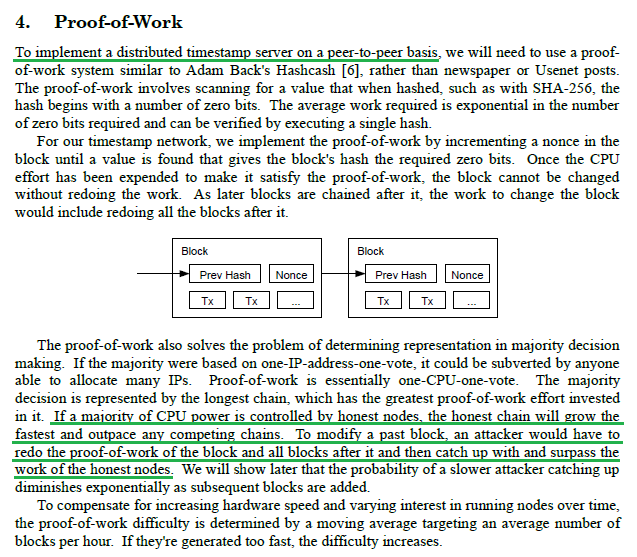

The “Section IV” theory

A second theory is that the answer to our question was given 10 years ago by the creator of Bitcoin. In the fourth section of the White Paper to be more specific.

Section 4

Section 4

I’m going to summarize this theory with the following sentence

The main utility of Bitcoin’s PoW is to secure an economic history.(1)

This is all well and good but in its current form this assertion isn’t very useful. A mathematical model would be far better. That raises a new question: how to express the “security of an economic history” as a mathematical equation ?

Digital Gravity

From the previous definition, we can state that our model should be able to express:

- economic values secured by the system (ideally, it should be able to do that atomically or in aggregate),

- the security provided to these economic values (or at least a good proxy metrics).

Since there’s no such thing as a “coin” in the Bitcoin protocol, our model will use the concept of Unspent Transaction Output (UTXO) as the elementary object of value.We can then easily define the total economic value secured by the system by adding the economic values of all the UTXOs existing at a given moment (UTXO set). Good. We already know how to express economic values in our model.

Now we need to express security. Obviously, PoW is going to play an important role here. Thus, it seems important to recall two of its properties

Proof of Work is Global and Cumulative

In a sense, PoW is similar to Gravity (to a homogeneous gravitational field to be more specific) which has a simultaneous influence over all bodies in its field, with a cumulative effect on their individual speed.

In the case of Bitcoin:

- when a new block is mined, the security provided by its PoW is simultaneously and equally applied to all the existing UTXOs,

- an UTXO “accumulates” the PoWs associated to all the blocks mined since its creation. All others things being equal, the more hashes accumulated, the more secure the UTXO.

These two properties are fundamental for studying the economics of Bitcoin’s PoW. Sadly, they’re totally missing in the metrics used by De Vries.

Let’s make a few assumptions

Before going further, let’s make a few assumptions:

- A1: For the last 9 years, Bitcoin has been the most secure public blockchain in terms of PoW.

- A2: At any given point in time, all existing and significant computing power usable for Bitcoin mining was used to mine Bitcoin.

- A3: The marginal cost and revenue of Bitcoin mining are equal.

- A4: Fees paid to miners are negligible when compared to block rewards and they can be ignored.

While these assumptions are likely to be more or less inaccurate in the real world, they seem good enough for this preliminary investigation.

Ok. Now, let’s try to translate this idea of the “security of an economic history” into a mathematical model.

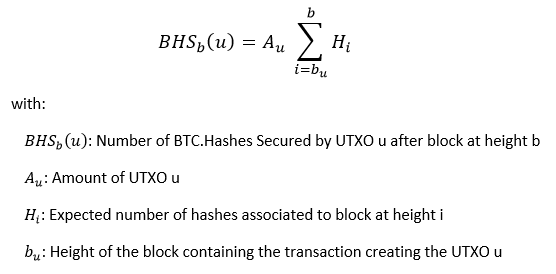

Number of “Bitcoin.Hashes Secured” by an UTXO

Our first attempt will be straightforward. Basically, we’re going to multiply the value of the UTXO by the number of hashes it has “accumulated” between its creation and a given block.

While simple, this definition captures the intuition that the system provides more utility when an UTXO has “accumulated” more hashes and/or when its value is higher.

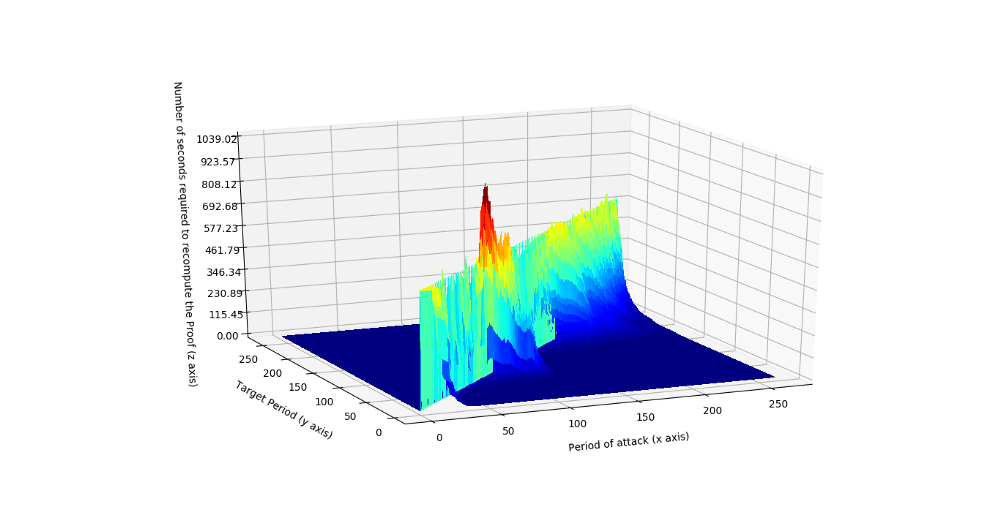

That being said, this model isn’t really satisfying because the number of accumulated hashes isn’t a very good proxy for measuring the security of an UTXO. The main reason is that the quantity of computing power dedicated to Bitcoin mining has greatly increased over the years. Thus, the computation of a PoW securing an old block may have required 10 minutes in 2009 but it will be computed in a fraction of that duration when done with modern ASICs.

Satoshi’s Wall (number of seconds required to compute the PoW of a past block with 100% of the average computing power used during the period between 2 difficulty adjustments)

It seems clear that we need a better model taking into account this fact.

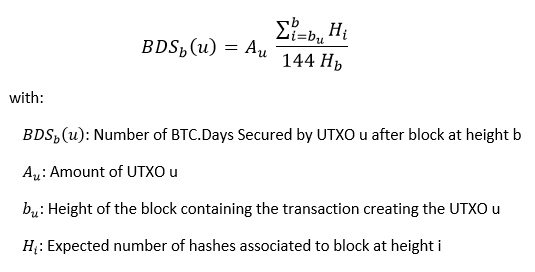

Number of “Bitcoin.Days Secured” by an UTXO

First, we’re going to add a new item to our list of assumptions

- A5: On large enough periods of time, the average amount of computing power dedicated to Bitcoin mining monotonically increases.

Once again, we can’t assert that this assumption is always true or will always be true. Anyway, it has been almost always true in the past, so let’s go with this hypothesis.

We can now define the security of an UTXO at a given block B as the number of days that would be required to rewrite the history since the creation of the UTXO, with 100% of the computing power used to mine block B.

For an individual UTXO that give us the following equation

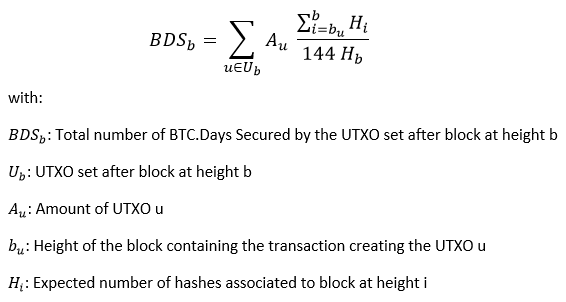

and the following equation for the UTXO set

You may wonder why this choice of “100% of computing power used to mine block B”. It’s simple. Under our current assumptions, we can consider this definition as a kind of worst case scenario (“How long would this UTXO remain secure if all the available computing power was used to rewrite the history ?”). Moreover, while an alternative scenario (50%, 200%, N%) would change the absolute values of our results, it wouldn’t change the overall evolution of the metrics over time.

Bitcoin’s PoW efficiency

All Right. Now that we have a model for the utility provided by Bitcoin’s PoW, let’s check what we can learn about its efficiency. For this, we’re going to define two metrics.

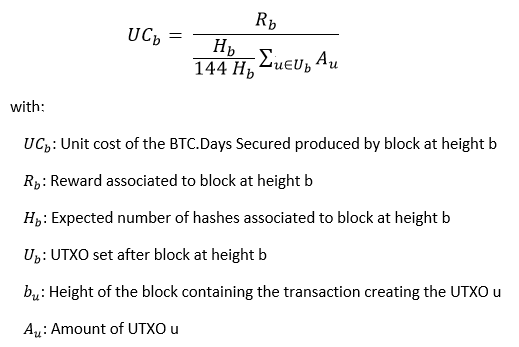

Unit Cost of a Bitcoin.Day Secured added by a given block

For this first metrics, we’re going to divide the reward associated to the block (c.f. assumption A3 about the margin costs and revenues of mining) by the number of bitcoins.days secured added to the existing UTXOs by the block.

It gives us the following equation

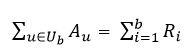

By definition, the sum of the values of all the existing UTXOs is the number of existing bitcoins and is equal to the sum of all past block rewards:

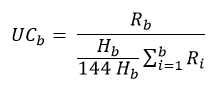

Thus our equation can be rewritten as

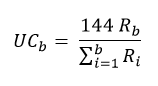

and finally simplified as

There are a few observations to be made here.

First, the Unit Cost is expressed by default in bitcoins/bitcoin.day secured but we would obtain the same result if we expressed it in USD/USD.day secured (both the numerator and denominator of our equation express the value of bitcoins at the same instant).

More importantly, it’s worth noting that the Unit Cost doesn’t depend on external factors like the market price or the number of hashes computed.

The Unit Cost only depends on the rules defining the controlled supply of the currency. It is defined by design.

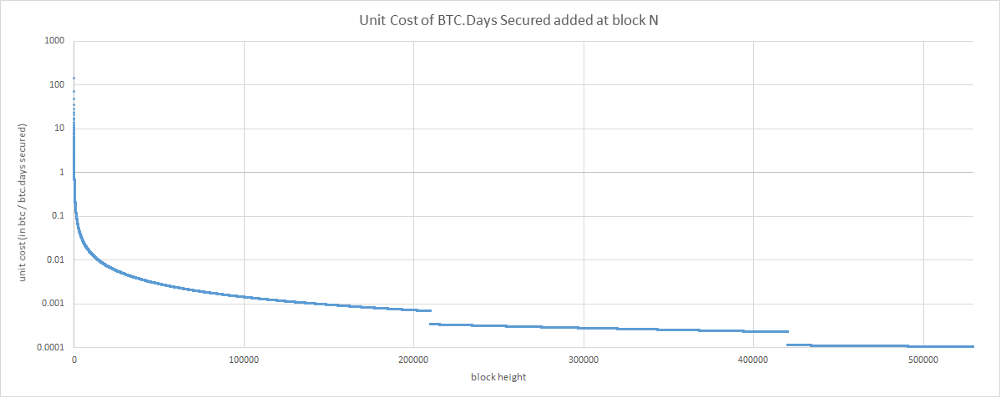

Let’s check the chart associated to this metrics

I guess that many people will be surprised by this chart but we can clearly observe that the Unit Cost is monotonically decreasing over time. This result can be explained by the joint influence of the deflationary model of Bitcoin(halving of rewards) and the temporary inflation caused by the creation of new coins. The situation should change when all bitcoins have been created. At this point, external factors will play a role on the evolution of the Unit Cost but it’s hard (if not impossible) to predict how things will evolve. Let’s note that the situation may also change before this date if/when fees become an important part of the mining incentive .

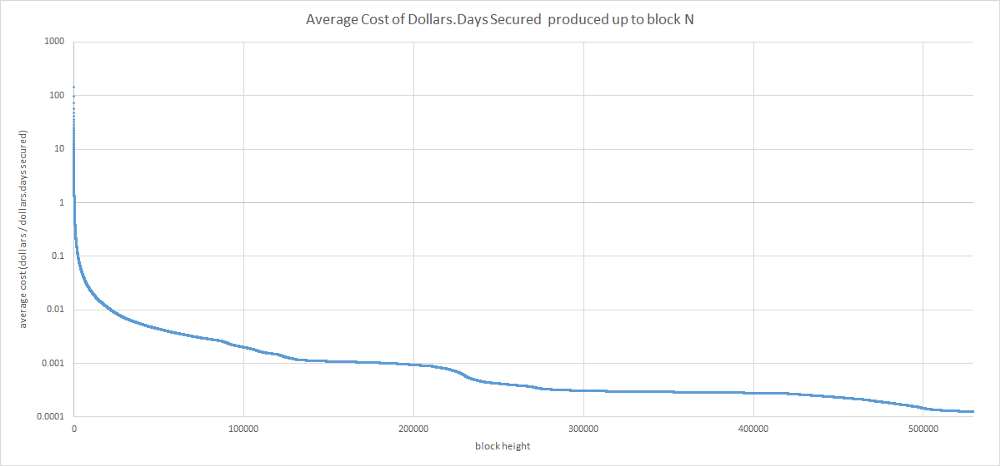

Average Cost of the Bitcoins.Days Secured added up to a given block

For this second metrics, we’re going to add all the costs expended on mining from the first block to the block of interest. Then, we’re going to divide this total cost by the sum of all the bitcoins.days secured created by these blocks.

Note that we’ll express all costs and UTXO amounts in USD because we need to deal with the value of UTXOs at different periods of time.

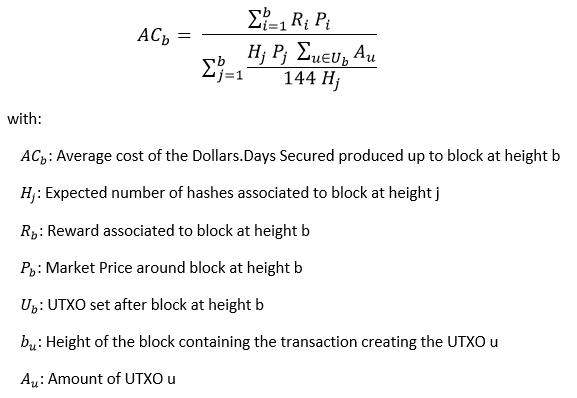

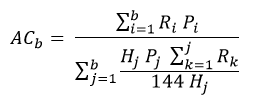

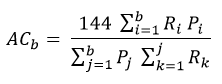

That gives us the following equation

which can be rewritten as

and finally simplified as

That gives us this chart

As it was the case with the Unit Cost, the Average Cost suggests that Bitcoin’s PoW is indeed becoming more efficient over time. This result might seem counter intuitive because of the apparent increasing absolute cost of Bitcoin’s PoW but it starts to make sense when we realize that this increasing cost is counterbalanced by the increasing total value secured by the system.

Conclusion

In this first part, we have discussed why the average cost per transaction isn’t an adequate metrics for measuring the efficiency of Bitcoin’s PoW and why this efficiency should be defined in terms of the security of an economic history.

Based on this observation and two important properties of Bitcoin’s PoW (its global and cumulative effects) we’ve formalized the utility of PoW with a very simple mathematical formula defining the total number of bitcoin.days secured by the system.

At last, we have derived two metrics which both suggest that contrary to a widespread opinion, Bitcoin’s PoW is actually becoming more and more efficient.

In the next part of this series, we’ll discuss a new metrics highlighting how the efficiency of the system has evolved under the influence of mining and hodling behaviors.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank @Beetcoin, Pierre P. and Stephane for theirs precious feedback and their patience. :)

A great thank you to @SamouraiWallet and TDevD for theirs feedback and their unfailing support of OXT.

Notes

(1) See Kocherlakota’s theory of “money [being] equivalent to a primitive form of memory” (R. Kocherlakota, Money is memory , 1996, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis) and Luther & Olson’s paper Bitcoin is memory (2014)