Statistical Fallacy behind the Lindy Effect

Statistical Fallacy behind the Lindy Effect

By Qiao Wang

Posted September 15, 2018

The Lindy Effect states that future life expectancy is proportional to current age.

Obviously, this does not apply to living beings. A 20-year old will likely outlive a 50-year old. But, allegedly, the opposite is true for nonperishable things like technologies and businesses. Every year that passes without extinction increases their future life expectancy.

The Lindy Effect was popularized by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his NYT bestsellers The Black Swan (2007) and Antifragile (2012). It was later adopted by the crypto community to argue in favor of older cryptonetworks like Bitcoin.

Barring a few anecdotal claims, I have not found any empirical evidence on the Internet that supports the Lindy Effect. Yet people use it to fit their narrative as if it’s a universal truth.

As we shall see, then, the Lindy Effect is merely a trivial statistical heuristic. In fact, it’s true almost by definition, and therefore not as useful as its proponents think it is.

Thought Experiment

Since there is no evidence for the Lindy Effect, let’s ask ourselves: if we were to empirically validate the Lindy Effect, how would we do it?

The way I would do it is the following:

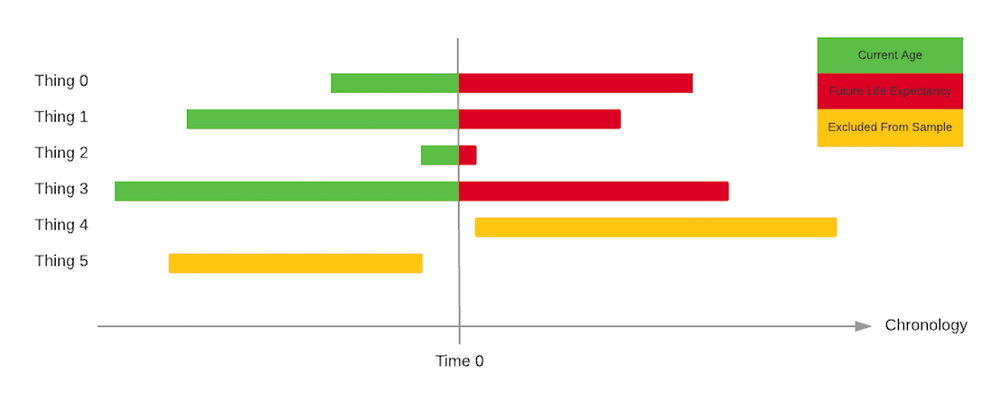

At time 0, which is now, I take a random sample of 10000 “things”. Technologies, businesses, commodities, religions, you name it.

For each of these 10000 things, I write down their current age α.

Now, time moves forward. I observe the future life expectancy of each of these 10000 things. I wait patiently.

As soon as one of these 10000 things “dies”, I write down their total lifespan τ. I do that until all 10000 things reach the end of their life.

The difference between the current age and the total lifespan, that is, τ - α, is defined as the future life expectancy.

So far so good?

The key insights here are that back at time 0,

- I don’t know at what percentage of their total lifespan I’m currently experiencing these 10000 things. I may be experiencing something at 10% of its total lifespan, or 90%, or 34.2436523%. I don’t know. I will only know in hindsight upon the end of its lifespan.

- There’s an equal probability I am experiencing that thing at 10%, 90%, or 34.2436523% of its total lifespan.

- By the very construction of the experiment, I cannot be experiencing something at <0% or >100% of their total lifespan. In other words, I cannot be observing something that is not yet born or including in my sample something that is already dead.

In statistical terms, these three points boil down to the following: α follows a continuous uniform distribution between 0 and τ.

It follows that at time 0, on average, I’m experiencing all 10000 things at 50% of its total lifespan.

As such, the current age α, whether is 1 minute, 1 year, or 1 century, is trivially the best estimator for its future life expectancy E(τ - α).

Implication

Notice that in the above experiment, current age is the only piece of information we know at time 0.

And this is the essence of the Lindy Effect. In the absence of all information except for current age, the best estimator for future life expectancy is the current age.

In real life, however, there is usually far more information you can incorporate into your prediction of the future. The Lindy Effect is thus a trivial heuristics, the usefulness of which decreases as if you acquire additional relevant information. For starters, the reason why we know the Lindy Effect does not apply to human life expectancy is that we have both empirical evidence and theoretical justification for why humans rarely live beyond a century.

Last but not least, the Lindy Effect is intimately linked to the survivorship bias. Recall the key insight #3 from above. The Lindy Effect is constructed in such a way that it looks only at things that are currently alive.

Appendix — Simulation of the Lindy Effect

I had some fun with Python.