How Cryptography Redefines Private Property

How Cryptography Redefines Private Property

By Hugo Nguyen

November 26, 2018

This is Part 3 of a 5 part series

- Part 1 - The Anatomy of Proof-of-Work

- Part 2 - Bitcoin, Chance and Randomness

- Part 3 - How Cryptography Redefines Private Property

- Part 4 - Bitcoin’s Incentive Scheme and the Rational Individual

- Part 5 - Bitcoin: Two Parts Math, One Part Biology

Cryptography is the art of protecting and breaking secrets. Bitcoin employs a special type of cryptography, called public-key cryptography, in order to facilitate its system of storing and transferring of value. It is through this mechanism that Alice can keep her bitcoins secure or send some of them to Bob, or that coinbase rewards are issued to the miners. The term “cryptocurrency” derives its name from this usage. In this third part of the Bitcoin Fundamentals series, we will explore the pivotal role public-key cryptography plays in the creation of digital hard money, as well as its ramifications on society at large.

To fully understand the significance of public-key cryptography, we must first take a few steps back and understand how our society is principally organized around the concept of property.

What is Property?

Property never has been abolished and never will be abolished. It is simply a question of who has it. And the fairest system ever devised is one by which all, rather than none, [are] property owners. — A. N. Wilson

Property has wide-ranging definitions. The idea of what constitutes property often changes to reflect contemporary beliefs and circumstances. For example, early discussions of property almost always exclusively referred to land. Since it was mostly land that was the source of constant conflicts and struggle for power, it was natural that land occupied the minds of ancient thinkers. Later, as society develops, property was expanded to include intangible assets such as patents and copyrights, and then expanded again to encompass all things deemed necessary for life and liberty.

Formally speaking, property is a legal concept defined and enforced by a local sovereignty. The specific implementation varies greatly depending on the political system, from monarchy to communism to democracy, among others.

Discussions on property dated back to Greek civilization. Plato and Aristotle, the two fathers of Western philosophy, laid much of the groundwork for the fierce and at times extremely bloody debates that followed in the subsequent 2,500 years.

Plato, likely inspired by the Spartans, was against private property of all sorts, including men’s wives and children. He rejected the idea of “mine” and “not mine”, “his” and “not his”. According to him, private property corrupts the human soul: it fosters greed, jealousy and violence. An ideal Platonic society would eradicate private property entirely. This school of thought was later developed into a full-fledged system, most notably by Karl Marx, the father of communism.

Aristotle, Plato’s best student, had other ideas. Aristotle rejected Plato’s argument that common property would remove vices and violence, arguing that people who share stuff tend to fight more than those who own them personally. Aristotle also believed that private ownership is crucial to progress because people would only be incentivized to work hard for the things they own. Furthermore, only when private property rights are respected, people can have the opportunity to fully grow and afford to be virtuous. As the late historian Richard Pipes eloquently put it: “Human beings must have, in order to be.”

Plato (427–347BC) and Aristotle (384–322BC)

Plato (427–347BC) and Aristotle (384–322BC)

Plato’s central argument against private property rested on morality. Aristotle also responded to Plato on the ground of morality. But some of Aristotle’s arguments went beyond morality and into the realm of economic reality. (Interestingly, like his teacher, Aristotle was against trade and profit-seeking, so he did not develop a consistent economic framework.)

The discussions on property since Plato & Aristotle have evolved to include mainly four aspects: morality, politics, psychology, and economics [1]. Among these, psychological and economical arguments for private property probably bear the most weight, since they address the world as it is, not how it should be.

One of the fundamental questions regarding property is that between property and sovereignty, which comes first?

Some influential thinkers, such as Harrington & Locke, believed that property predated sovereignty. They believed humans intuitively understand property, even without the existence of a state.

To them the primary function of a state is to protect property rights. A sovereign state is judged on its merits to fulfill this responsibility. Locke went further and stated that individuals have the right to rebel against the state if it fails in its duty to preserve property rights. Adam Smith, the father of capitalism and modern economics, had a similar view. Smith recognized that property and government were dependent on each other, and argued that “civil government could not exist without property, as its main function is to safeguard property ownership”. (Smith differed with Locke, however, on whether property rights are “natural” — he believed property rights are “acquired” rights, not “natural” rights).

In contrast, other thinkers, most prominently Hobbes, believed it was the opposite, that property is a creation of the state. He regarded property simply as the product of authority and the acceptance of that authority [2].

There has been mounting evidence, particularly in the later half of the 20th century, that vindicated Harrington’s & Locke’s view. The 20th century saw a large-scale social experiment in attempting to abolish private property via the spread of communism. This experiment resulted in the Cold War and numerous proxy wars across the globe, culminated in the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, and ended dramatically when the Soviet Union finally collapsed in 1991. Following this collapse, the remaining communist states were split into two camps. Some switched to capitalism, as many Central & Eastern European countries did. Some retained only a nominal form of communism, as China & Vietnam did — in these countries the political regime purports to represent the “bourgeois”, but the economy functions much like that of a capitalist state. Almost all surviving communist states have adopted free-market ideology, and were forced to respect property rights (to a certain extent) in order to survive.

In summary, what the 20th century has shown us is that governments that failed in their primary role of protecting property ended up either dead or forced to eventually respect private property. This proves that the state is subservient to, and is a derivative of, property needs, not the other way around. Property, by and large, comes before the state .

Despite this, in the short to medium term, individuals do have to depend on the state for preserving their property rights, and suffer a great deal when it fails to do so. We will see how cryptography can help break this cycle of dependency. But first, let’s quickly look at how modern cryptography came about.

Public-Key Cryptography

Until recently, the development of cryptography has been driven mainly by wars and rivaling states.

Prior to WW2, classical cryptography was more about obscurity than mathematical rigor. If there was any math involved, it was simply accidental. This changed with a couple of developments:

- The invention of the telegraph dramatically increased the amount of data that needed to be secured

- The invention of the radio heightened the need to encrypt public communication channels, as opposed to relying on stealth methods

- The invention of the computer brought incredible computational power to cryptanalysis; breaking codes became much easier

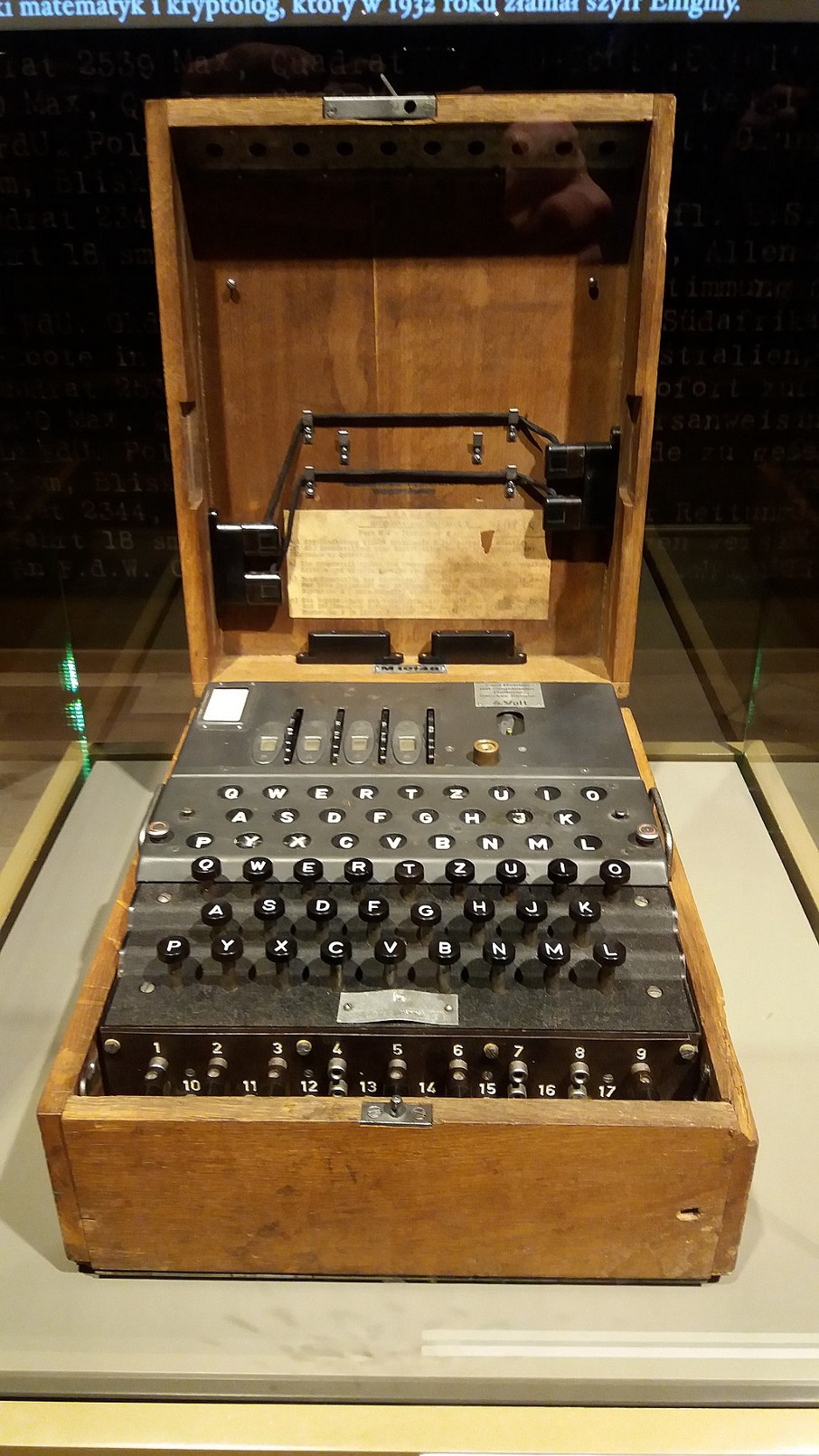

These developments culminated in WW2 and saw the Allies heroically break Germany’s state-of-the-art cryptographic device, the Enigma machine, with notable help from Alan Turing. The breaking of Enigma decidedly concluded the era of classical ciphers (a cipher is a particular method of doing encryption and decryption) and called on cryptographers to look for stronger ciphers — ciphers that are based on a more solid, mathematical ground.

End of an era: the Enigma machine — image by LukaszKatlewa, CC 3.0

End of an era: the Enigma machine — image by LukaszKatlewa, CC 3.0

Luckily, there were hints for where to look. One major problem with classical ciphers was the problem of secret keys distribution—a problem common to all symmetric ciphers (symmetric ciphers are ciphers that use the same key for encryption and decryption). Basically, with symmetric ciphers, since it is not recommended to reuse secret keys, the number of keys that need to be distributed is proportional to the amount of data that need to be secured — which as mentioned, exploded at an unprecedented rate. As a result, one big research area at the time was to find ways to cheaply and securely distribute keys at scale. The insight for asymmetric ciphers began when a few cryptographers flipped this problem on its head and pondered: do we actually need to distribute the secret keys at all?

This research direction eventually narrowed the search down to one-way functions, and it was not long until a brand new solution was found — one which does not require the distribution of secret keys. Diffie, Hellman & Merkle discovered public-key cryptography, the first ever asymmetric cipher, in 1976. One year later, Rivest, Shamir & Adleman published the first implementation, the now-famous RSA algorithm. Public-key cryptography was also independently discovered, but not implemented, a few years earlier by Ellis & Cocks in Great Britain. However, Ellis & Cocks’ research was classified and not publicly acknowledged for 27 years.

Thus, public-key cryptography, today considered the greatest cryptographic achievement in two thousand years, was born. It took several decades for this technology to filter down to the masses, largely thanks to the efforts of the cypherpunk movement. The cypherpunks, foreseeing that the state’s monopoly on this new technology creates a huge imbalance of power and a potential threat to individual liberty, took incredible risks to bring public-key cryptography to civilians. When they successfully did, the gates were flung wide open. For the first time in history, individuals could afford encryption as strong as the military’s.

But it was not until the invention of Bitcoin that public-key cryptography realizes its full potential. Its application in digital hard money would redefine private property.

Privately-Owned Digital Goods: An Oxymoron?

The arrival of the personal computer and the Internet introduced a new asset class: digital goods. Digital goods are intangible digital bits of information, packaged in various encoding formats. Examples are Wikipedia articles, MP3 files, software, etc.

Digital goods ushered in a new era of information-sharing never before seen. Any piece of information could be instantly reproduced and distributed at scale, at almost zero marginal cost.

However, early on digital goods did not significantly change the nature of private property. As it turns out, digital goods are notoriously bad at staying private.

The problem with trying to establish exclusive ownership over digital goods is that they are infinitely copyable. But that did not stop people from trying anyway. The state and businesses’ preferred method of imposing control over digital goods is through regulations. For example, the US created a complex export control & regulations program to prevent secrets, particularly knowledge of advanced technologies, from leaking to other states. In business, the Big 3 music labels and the Big 5 movie studios spend a large amount of money lobbying for anti-piracy laws, and suing people for violations. Similarly, big software companies learn to build patent war chests. In the process they exploit the patent system and cripple smaller companies. At best, regulatory solutions at enforcing digital exclusivity are expensive and ineffective. At worst, they create an environment where a few players can game the system to their advantage.

Non-regulatory solutions are equally inefficient. One such example is Digital Rights Management (DRM), an access-control technology designed to restrict the use of digital goods. DRM does provide some basic level of security against piracy. However, DRM suffers from a fatal flaw: the security only needs to be bypassed once, and there would be no recourse.

One area where we saw limited success at creating digital exclusivity came from the gaming industry. Game creators figured out that if they could create virtual goods (a subset of digital goods) within the games they designed, these goods could serve to add to the gameplay, as well as a nice bonus source of revenue. Since the game creators control 100% of the environment within which these virtual goods operate, they could impose restrictions on them that are not possible otherwise, including making them inaccessible or rare. However, in-game virtual goods have limited application, and game users are dependent on the game creators to not change the game rules.

So it might have seemed like digital goods and private property are at odds. If something is digital, it is almost impossible for it to be private or for someone to have sole possession of it. Privately-owned digital goods sounds like an oxymoron.

The inability to exclusively own digital goods means that everyone can take advantage of them. Individuals can use them to empower themselves, but the state is also able to become more powerful through data collection, surveillance, and propaganda — all made easier with digital goods. Digital goods, in their pure form, do not change the power structure between the individuals and the state.

But there is a way for digital goods to become private property, only if we can overcome 2 major hurdles:

- Scarcity: the ease of reproducing and redistributing digital goods in unlimited quantity is precisely what makes exclusive ownership difficult.

- Transferability: the ability to dispose of an asset by sale is a crucial component of ownership. Without this, ownership loses much of its power.

It turns out that these two desired attributes are also the prerequisites of money. If we are able to create a digitally-scarce, transferable digital good, not only this good could be privately owned, it would become a great store-of-value and ultimately a new form of money. Digital “hard” money.

Bitcoin solves both problems. Bitcoin creates digital scarcity by imposing a fixed supply on itself in software (a.k.a. consensus rule), and then protecting that consensus rule with a large amount of energy (in the form of Proof-of-Work) through a decentralized network of mining machines. As long as mining is sufficiently decentralized, it would be nearly impossible to change this fixed supply rule or bring down the network. We discussed this key innovation in-depth in Part 1 of the series.

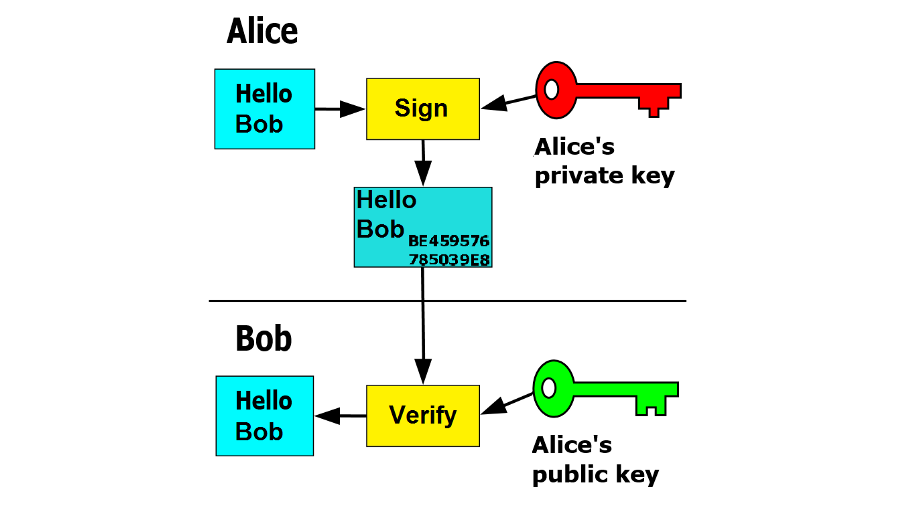

The problem of transferability, on the other hand, can be solved by using public-key cryptography. Specifically, a unique application of public-key cryptography is to generate unforgeable digital signatures. The digital asset could be coupled with a public-private key pair. This single key pair could then generate as many digital signatures as needed, each one represents a piece of the underlying asset. These digital signatures effectively “tokenize” the asset, making it transferable between individuals [4].

In short, public-key cryptography, together with digital scarcity, have given us digital hard money. Digital hard money inherits all the strengths of digital goods: instant, borderless, and impossible to regulate or control. Most importantly, this digital hard money can be privately owned.

Digital signatures using public-private key pair — image courtesy of Wikipedia, CC 4.0

Digital signatures using public-private key pair — image courtesy of Wikipedia, CC 4.0

It is hard to overstate how big of a disruption this is.

For the first time in history, a form of private property exists that is completely independent of jurisdiction or the law [5]. Private keys and the bitcoins they control are private property de facto, not de jure.

Public-key cryptography’s application in digital hard money greatly changes the social contract that has bound human societies for thousands of years: that individuals need the state for the protection of property, and the state in turn needs individuals to finance its continued existence. One has to wonder, if securing property is the primary function of a state, then will its role — and power — be significantly reduced in a world run on digital hard money?

In summary, public-key cryptography’s application in digital hard money redefines private property and has the potential to uproot the very foundation of society as we know it. The consequences might take decades to play out, but when it happens, the impact will likely be incredibly far-reaching.

*This is part 3 of the Bitcoin Fundamentals series. Check out the full series here: part 1 , part 2 , part 3 , part 4 , and part 5 .

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Jimmy Song, Hasu, Nic Carter and Steve Lee for their extremely valuable feedback.

[1]: Property and Freedom, Richard Pipes

[2]: Property and Ownership , Jeremy Waldon

[3]: The Code Book: The Science of Secrecy from Ancient Egypt to Quantum Cryptography , Simon Singh

[4]: It is very possible that public-key cryptography is the only way to tokenize a digital asset this way. Imagine implementing Bitcoin using a symmetric cipher.

[5]: Physical assets like gold can be and often is heavily regulated. For example, FDR outlawed & confiscated private gold during the Great Depression.

Thanks to Steve Lee, Hasu, Nic Carter, and Jimmy Song.