Bitcoin Timestamp Security

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

Bitcoin Timestamp Security

Jameson Lopp

Posted March 3, 2019

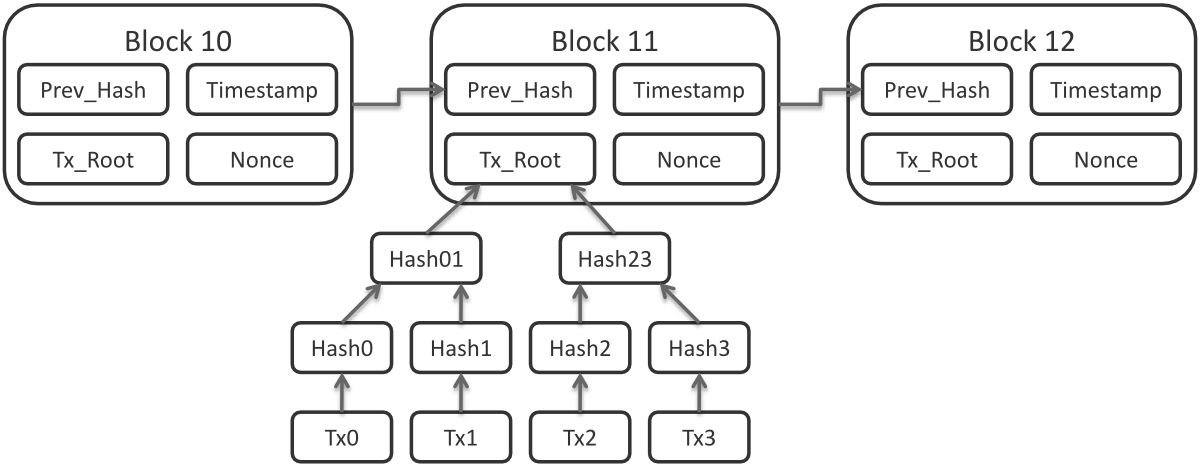

Bitcoin is often referred to as a secure timestamping service. We never had a global record of truth with trustworthy timestamps, so how did this come about? It’s generally due to Proof of Work being combined to a few simple rules by which miners must abide. The primary functions of miners are to:

- Take unordered unconfirmed transactions and put them in a specific order

- Bundle up the transactions into a valid container (block)

- Timestamp the block within an acceptable range of time

This final attribute is what enables Bitcoin to have a controlled release of the supply of bitcoins. Otherwise Bitcoin would suffer from rapid inflation whenever the hashrate increased. But it turns out that this attribute assigns quite a bit of utility to the Bitcoin protocol and also makes it possible for folks to use Bitcoin as a data anchor for other services. Because we have reasonably strong assurances that timestamps fall within a given range and we have mathematical assurance of the amount of energy required to rewrite the blockchain history, Bitcoin provides a sound anchor for timestamping of data. But how reliable is it?

Bitcoin’s Timestamp Flexibility

In order for the time field of a block header to be considered valid by nodes it must meet two criteria:

- Be less than 2 hours in the future from your computer’s current time

- Be greater than the median timestamp of the past 11 blocks

The first rule makes sense — we obviously don’t want anyone claiming to be from the future and it’s very easy for nodes to reject such claims because we’re all in general agreement about what time it currently is. There are a variety of ways that one can check the current time, though a very popular means of computers syncing their clocks is via the Network Time Protocol.

However, ensuring that the time isn’t too far before a sensible point is harder. This is because we can’t assume that a node is validating the block anywhere near the time it is initially created. Nodes need to be able to leave and rejoin the network for any reason or no reason. A node that was too far behind the tip of the chain would start rejecting historical blocks if they had to be created within a few hours of the current time.

“Nodes can leave and rejoin the network at will, accepting the proof-of-work chain as proof of what happened while they were gone.” — Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin Whitepaper

Perhaps counterintuitively, there is no rule requiring that a block’s timestamp has to be after the timestamp of the previous block. If you think about it, such a rule could cause problems — if a miner created a block with a timestamp nearly 2 hours in the future, the next block would also have to be far in the future — it would be harder for other miners to self-correct the median time of the past 11 blocks.

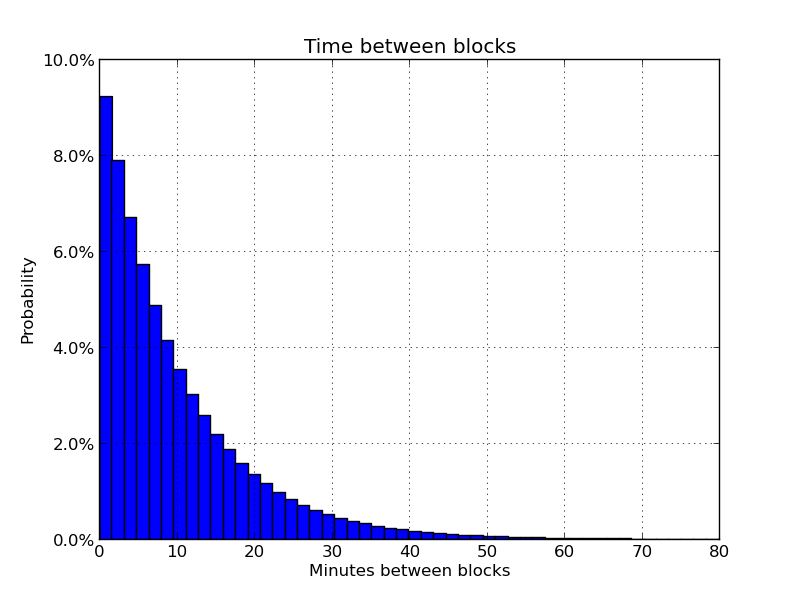

Also, recall that while blocks are expected to be produced about every 10 minutes, there is no real guarantee. Blocks could range from anywhere from several milliseconds to several hours apart. While the expected median time of the past 11 blocks should be 1 hour ago, it could be far more or far less.

Source: https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Confirmation

Source: https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Confirmation

Pushing the Window

If you think about how an adversary might try to expand the acceptable timestamp window, it’s pretty clear that no adversary will be able to push the timestamps to be more than 2 hours in the future, no matter how much hashpower they have. However, an attacker with sufficient hashpower could put some drag on the progression of “bitcoin time” by only minting blocks with timestamps that are barely valid — that are just one second after the median time of the past 11 blocks.

Are there incentives to do this? In the extreme case a “time warp attack” offers short term financial incentives that we’ll discuss later. It’s less clear what incentives may exist for only dragging the timestamps by a few hours here and there. Though considering that other protocols can be built on top of Bitcoin (such as Lightning Network) and can involve time locks, there could be other protocols in the future that can be gamed by slowing the progression of timestamps on the blockchain.

Hashpower Time Dragging

Since the earliest valid block time is based upon the median time of the past 11 blocks, an adversarial miner needs to generate a lot of blocks in order to induce any noticeable drag on the MTP.

Let’s assume a situation where all miners are roughly in sync via NTP but there is one adversarial miner who is trying to drag the median time of the past 11 blocks as much as possible.

One point is quite clear: it was a smart decision by Satoshi to use the median timestamp of the past 11 blocks rather than the average, as average would be more manipulable. Another way to think of “median time past” is that it basically means the timestamp of the 6th most recent block if all of the timestamps are in order. If they aren’t, the algorithm just re-orders them. As such, if you want to have a non-negligible effect on this value you need to have solved 6 of the past 11 blocks. In order to sustain such an attack you’d need 55% hashpower, at which point one of the main assumptions of Bitcoin’s thermodynamic security breaks down. But a miner with less hashpower could still achieve this on occasion if they have a streak of luck.

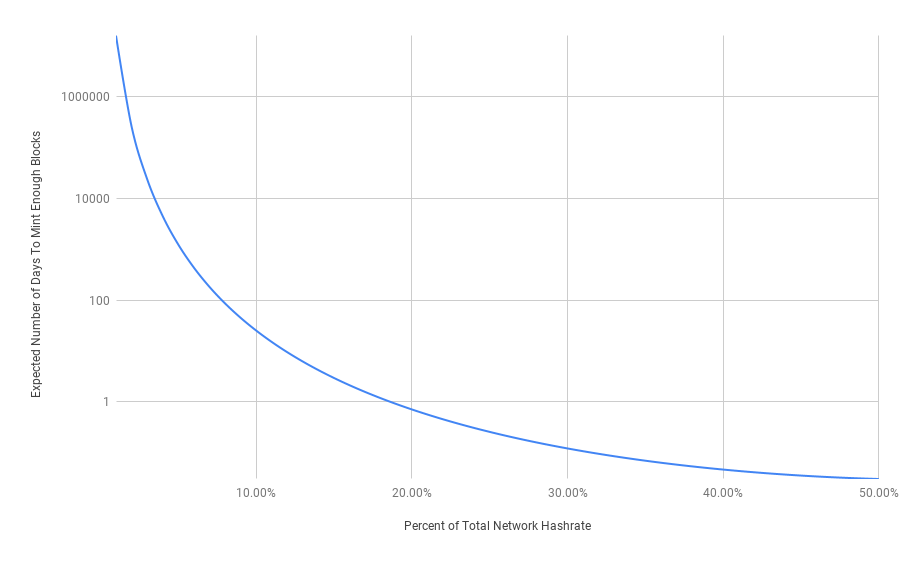

How hard is it to find 6 out of 11 blocks? Well, the chance that a given miner will solve the next block is basically the same as their percentage of the total network hashrate. Thus, if you only have 1% of the hashrate (which is still quite a lot) then your chance of minting 6 out of any 11 contiguous blocks = (0.01⁶0.99⁵)( 11!/(5!6!)) = about one in 2 billion. If you maintained 1% of the hashrate then the expected number of blocks that would need to occur before you found 6 out of 11 would be over 43,000 years.

A more generalized formula for the expected wait time to pull off a successful time drag attack would be:

(1 / (462 * (% hashrate⁶ * (1- % hashrate)⁵))) / 144 blocks/day = # days

As we can see, for attackers to conduct such an attack on any meaningful timescale then they’d need a decent size mining pool with at least 10% of the total network hashrate.

Maximum Drag

However, in order to induce the maximum drag on the MTP a miner would want to solve 6 blocks in a row. If their 6 of the past 11 blocks are not all in order, then time gaps created by other miners would force the adversarial miner to set the timestamps of their blocks more than one second after each other because the MTP for each block would jump forward significantly as honest miners place more accurate timestamps on their blocks.

How hard is it to solve 6 blocks in a row? If we once again assume a miner with 1% of the network hashrate then the chance of minting any given streak of 6 blocks in a row is 0.01⁶ = roughly one in a trillion. If you maintained 1% of the hashrate then the expected number of blocks that would need to occur before you found 6 in a row would be nearly 2 million years.

A more generalized version of the expected time to successful time drag attack formula would be:

(1 / % hashrate⁶ ) / 144 blocks/day = # days

This attack is even more difficult to pull off, requiring more like 20% or 30% of the network hashrate to occur in a reasonable timeframe. As you may imagine, this happens quite rarely and when it does, people notice. The last times it happened were in July 2014 by GHash, which had over 40% of the hashpower for a while and even touched 51% for a short time. It also happened 9 months earlier when BTC Guild had nearly half of the hashpower. If you have 50% of the hashpower then your chance of minting 6 blocks in a row is 0.5⁶ = one in 64. If you maintained 50% of the hashrate then you could expect to find 6 blocks in a row nearly every 12 hours.

It’s clear that it’s not possible to sustain a drag on Bitcoin’s Median Time Past on a long term time scale without majority hashpower, but you could drag it by as much as several hours for a short period (a block or so) with the right combination of luck and patience. If you assume that other miners are fairly accurate with their timestamps, then the median time past should be approximately 1 hour ago, though it could be several hours more due to the variability in blocks being found. If you manage to mint 6 blocks with timestamps of 1 hour ago plus 1 second, 2 seconds, 3 seconds, etc then at the 6th block the MTP would be approximately 2 hours ago. If we assume an extreme condition of 1 hour gaps between blocks, then the MTP would be 6 hours ago.

By allowing a reasonable amount of flexibility with block timestamps and then taking a median time of recent blocks, we end up with an algorithm that is pretty hard to game but is not so brittle as to adversely affect miners who are somewhat out of sync with the real time.

Let’s Do the Time Warp Again

What if an attacker did have more than 50% of the network hashpower and they wanted to slow the passage of Bitcoin time? They could do some pretty nasty stuff. Such an adversarial miner could prevent the timestamp from advancing by more than 1 second with each new block. If they did this for a long enough period of time and ended up creating blocks on the difficulty retarget intervals with timestamps that made it look like the previous 2016 blocks took far more than 2 weeks to create, they could game the retargeting logic to decrease the mining difficulty by up to 75% every 2016 blocks. Eventually with the difficulty low enough, they could mint as many blocks as they wanted in a given time period and thus receive more mining reward than expected. An optimized time warp attack could mine all the remaining bitcoin in 18.7 days. We’ve actually seen similar behavior occur on Bitcoin’s testnet3 due to a quirk in the difficulty retargeting and now testnet3 has minted 1,482,878 blocks in 8 years, about 350% of the expected emission.

Time warp attacks are nothing new. Such an attack was first performed against a coin called “Geist Geld” in 2011 and it was discussed as being a “variant of the 51% attack” on BitcoinTalk. Geist Geld was intended to test out the upper limits of block generation rate via very short block times, as well as the behavior of a cryptocurrency with (almost) stable generation rate and no upper limit or alteration to supply.

Whitecoin appears to have also suffered from a time warp attack that was conducted in 2014.

In 2018 Verge was hit by such an attack. And then 6 weeks later it was hit again!

In general, cryptocurrencies that have a minority of hashpower for a given style of hardware (ASICs or GPUs) are vulnerable to time warp attacks because they are inherently vulnerable to 51% attacks.

Interestingly, while time warping is often referred to as an attack because it results in unintended behavior of the system, some people have shown that it can be exploited for potentially desired uses. In 2015 Vitalik Buterin described a way to speed up blocks via a soft fork and thus increase on-chain capacity. In 2018 Bitcoin developer Mark Friedenbach made a proposal for leveraging this unintended behavior in order to add new functionality to Bitcoin. In his “Forward Blocks” proposal, Mark states that his method enables scaling up on-chain transaction volume to 3584X current levels, changing the proof-of-work algorithm in a backwards compatible way, sharding, a rebateable fee market for consensus fee detection, and smoothing out drops in miner subsidy along with prerequisite protocol pieces for confidential transactions, mimblewimble, unlinkable anonymous spends, and sidechains.

Such proposals are contentious, however, and would likely force anyone building systems reliant upon the timestamps in the Bitcoin block headers to look elsewhere for that data. It would also be fairly easy for such a change to be blocked, as Greg Maxwell stated on the Bitcoin developer mailing list:

It can be fixed with a soft-fork that

further constraints block timestamps,

and a couple of proposals have been

floated along these lines.

In Conclusion

Bitcoin’s timestamp security and the simple rules constraining the window of acceptable timestamps have withstood 10 years in an adversarial environment despite their known weaknesses. We know that a 51% cabal of miners could wreak havoc on the network, at least for a short time, but this has never happened — likely because the incentives are not aligned for miners to do so. Rational miners would not choose a short term gain in return for killing the long term golden goose.

Thanks to Jimmy Song and David A. Harding.