Bitcoin Has a Branding Problem - It’s Evolution, Not Revolution

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

Bitcoin Has a Branding Problem — It’s Evolution, Not Revolution

For technologists and historians, it may well be a revolution; but for everyone else — it’s an evolution in personal finance.

By Ryan Radloff

Posted March 6, 2019

Before we get started I’ve broken this post out into two parts to address the point, so please bear with me regarding format.

Part 1 — I take a look at how our financial lives trend towards convenience (and as a result, dependence on intermediaries); and whether we should expect that to change anytime soon.

Part 2 — I look at the larger evolution of assets from physical to ‘digital’ over the last 35+ years; and where bitcoin fits in that trend.

Both parts are important to illustrate a critical point — for the end user, bitcoin doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It exists on a spectrum of evolution for consumers and the best thing we can do to drive adoption is acknowledge this nuance.

Langley, N., Garland, J., Morgan, F., LeRoy, M., Ryerson, F., Haley, J., Bolger, R., … Baum, L. F. (1939). _The wizard of Oz_. Hollywood, Calif.: Metro Goldwyn Mayer.

Langley, N., Garland, J., Morgan, F., LeRoy, M., Ryerson, F., Haley, J., Bolger, R., … Baum, L. F. (1939). _The wizard of Oz_. Hollywood, Calif.: Metro Goldwyn Mayer.

Part 1: Trending Towards Convenience (Dependence)

As an American residing in London, it takes me around two weeks from the moment I walk into a local bank branch to complete the arduous and highly manual process of verification (a.k.a. Know Your Customer) in order to become an account holder.

This system is so inefficient that it has birthed a new array of challenger banks (e.g. Revolut, Monzo and Starling Bank). These banks focus on eliminating the inefficiencies and friction of traditional banking, and claim to put us more in control of our finances than ever before.

This model and mission has driven rapid growth for the aforementioned companies, and altered our notion of what a bank looks and feels like.

Yet at the same time, it’s a model and mission which, to borrow from The Wizard of Oz, asks us to “ Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain…“

…and perhaps more than ever before, that is the paradox at play here.

Pay No Attention to That Man Behind the Curtain

While new Fintech banks/platforms provide the illusion of closer proximity to our finances, in many cases these platforms are nothing more than a re-engineered interface for the traditional financial system, with new branding.

For example, Yolt is really just a slick front-end for Dutch multinational bank ING; Wealthify, a brilliant UI owned by Aviva; Zelle — founded by Bank of America, Wells Fargo and JPMorgan Chase — backed by even more banks; and Nutmeg, the mobile choice for investment management, is substantially owned by Goldman Sachs.

Sure, with a few taps I can send £4 I owe you for that latte faster than ever before. But the net result (trade-off) of the rapid digitalisation of the financial system is a requisite increase in specialised financial intermediaries layered on top of each other, built to eliminate the ‘friction’ points of the legacy world.

And here lies the paradox:

While we’ve been hit with slogans like ‘ New Money’_as we venture deeper down the path of convenience banking, we’re really just interacting with a new facade of the legacy financial system.

With that context, it’s easy to understand why people are confused when a truly digital, fully bearer asset enters the picture — ’ New Money’ incarnate.

We don’t initially understand 1) how it’s different than what we already have and 2) why we should ever be concerned about what is going on behind the curtain of our new digital banks.

After all… we’re in control of our finances, not them — so who cares?!

To the second point, what most people don’t realise is the unfortunate reality that the existing system has ‘evolved’ into an incredibly complex web of financial intermediaries built on top of and around each other. All meant to distribute risk more evenly (yet rarely do), the actual result is an opaque fiefdom for risky (and unscrupulous) behaviour.

Look no further than some of these headlines from the last few years…

- HSBC to pay $1.9 billion U.S. fine in money-laundering case

- Watchdogs impose $3.4B fines in bank forex probe

- Deutsche Bank settles silver, gold price manipulation suits

- Banks face $1bn bill over fees-for-no-service scandal

- JPMorgan to pay more than $135 million for improper handling of American Depositary Receipts (ADRS)

- Wells Fargo is paying $575 million to states to settle fake account claims

This isn’t even to mention banks’ central role in the 2008 financial crisis, the lasting effects of which have been well documented and which no doubt impacted countless families in immense ways — my own included.

As Elaine Ou opined for Bloomberg:

“Financial institutions make people feel safe by hiding risk behind layers of complexity. Crypto brings risk front and centre and brags about it on the internet.”

And to the first point regarding how digital assets are different than what we already have… those outside of crypto-land have their PayPal app, their Venmo accounts and can easily send $4 internationally to a friend without using Bank of America or Barclays. Why do they need anything new, much less a revolution?

Revolution is a rallying cry for early adopters, and a historians’ view on what is actually evolution, in real-time.

Revolutions are inconvenient, messy and disruptive to the status quo, a default which we are unfortunately biased towards.

Revolutions often only happen as an absolute necessity, when ‘society’ has exhausted all other options and tensions have evolved to a breaking point.

So when outsiders (read: people we would like to eventually opt-in to this new system) hear the “revolution” declaration from bitcoiners, it simply doesn’t resonate. Humans are wired to seek confirmation of our own biases and be sceptical of new ideas that challenge or threaten our worldview.

The Evolution Amidst the Revolution

Challenger Fintech banks are winning hearts and minds by capitalising on the weaknesses of bigger, bulkier competitors. Legacy banks are now ‘evolving’ with their own facades meant to capture those same hearts and minds.

Consumers are loving the evolution toward convenience and ‘control.’

I would argue that Bitcoin is simply part of this larger migration away from our parents “brick and mortar” banks toward more nimble, digital financial services.

While Bitcoin is a revolution with respect to approach, infrastructure and (dis)intermediation; to the consumer, it will (and should) feel like it is part of the same evolution that they have been part of all along.

Although Bitcoin does indeed seek to revolutionise the financial industry by separating money and state, “revolution” doesn’t need to be the lede.

From most people’s perspective, we’ve gotten along just fine paying no attention to that ‘man behind the curtain.’ Why should we expect to change that behaviour en masse all of a sudden?

Part 2: Reframing Bitcoin in the Progression to Digital Finance

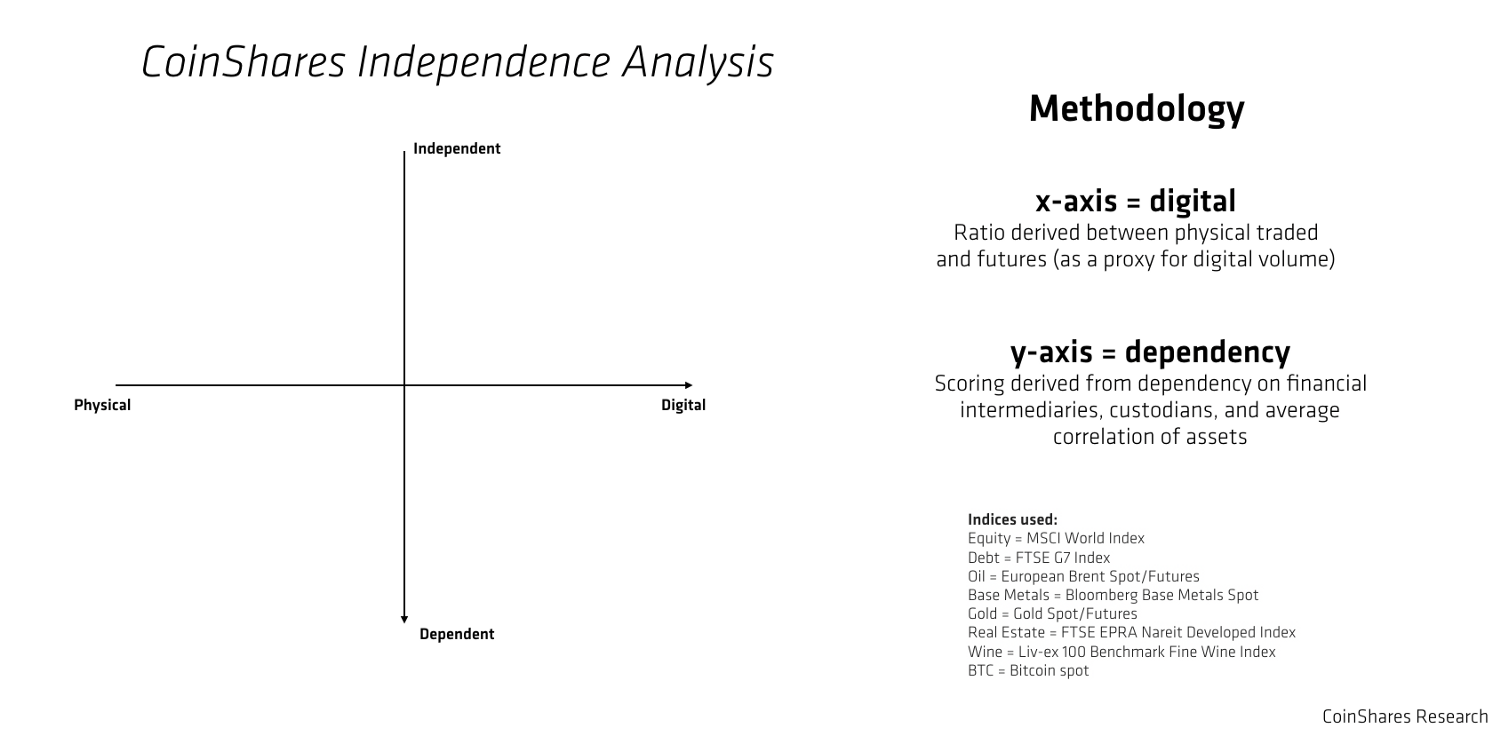

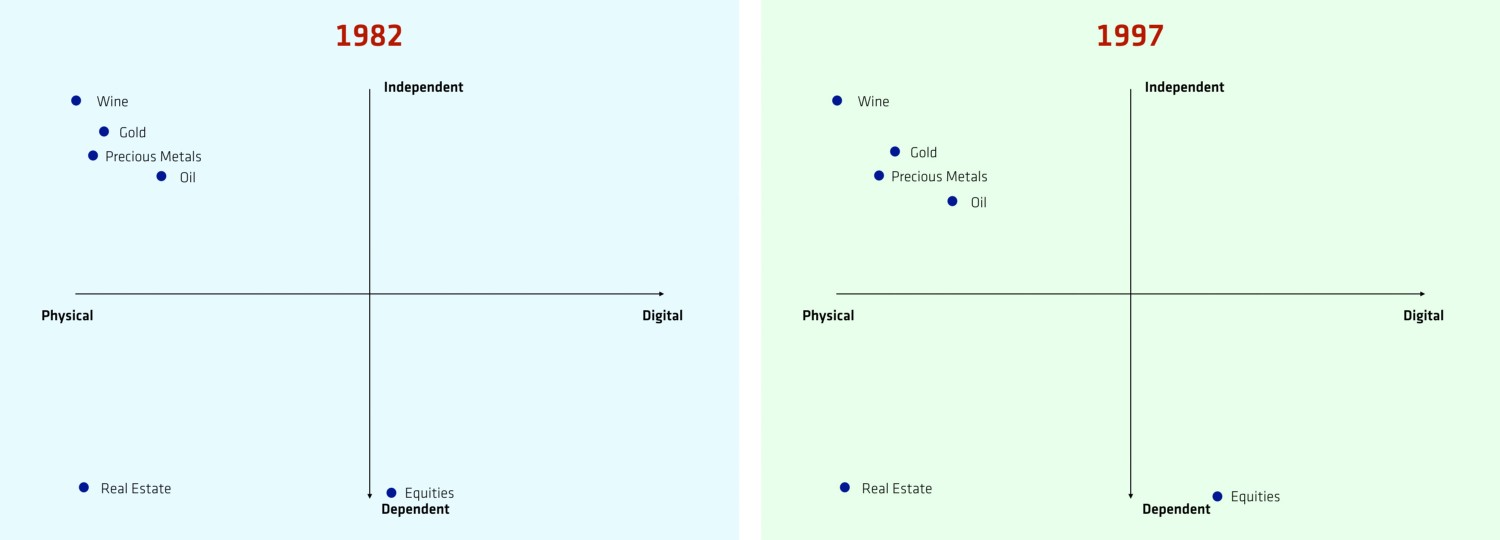

In an effort to track the larger progression towards digital finance (an evolution over 35+ years in the making), our research team at CoinShares developed a qualitative approach that plots the dependency of an asset on financial intermediaries against how digital an asset is (as defined below).

As I touched on in the previous section, we witnessed an explosion in the number of financial intermediaries as we’ve moved towards ‘convenience banking’. The truth, however, is that the number of intermediaries has been mushrooming for much longer, coinciding with a shift in preference towards digital proxies for financial assets.

For the purposes of this exercise, we defined “dependency” as an asset’s dependence on — or independence from — third-party intermediaries in order to buy, sell, and custody said asset. We’ve plotted this on the y-axis in the charts below.

On the X-axis, we plotted how “digital” an asset has become. This was measured by tracking the preference to interact with that asset in a non-physical, ‘proxied’ format (i.e. digital) — whether it be an ETF, option, future, etc. — rather than the underlying asset itself.

For both of these measures, we used quantitive data whenever available, and supplemented with qualitative observations when it was not. In these instances, we identified specific inflection points to warrant movement on the ‘dependency’ y-axis.

For example, fine wine is generally considered an illiquid asset. In 1982, it was tradable in rare circumstances when a buyer and seller were paired. Yet in 2000, Liv-ex launched to bring transparency and efficiency to fine wine trading via an electronic exchange. A few years later, they launched the Liv-ex 100 Fine Wine Index. Today, there are a number of structured investment vehicles (e.g. the Vinculum Wine Fund) that offer exposure to this asset class — beyond purchasing the wines themselves; but this also introduced new intermediaries to the process.

Across nearly all asset classes, as transactions shifted to the digital sphere, they required more intermediaries; and as a result, rendered assets ‘more dependent.’ The exceptions were equities and real estate, which involved a number of intermediaries even before this shift to digital.

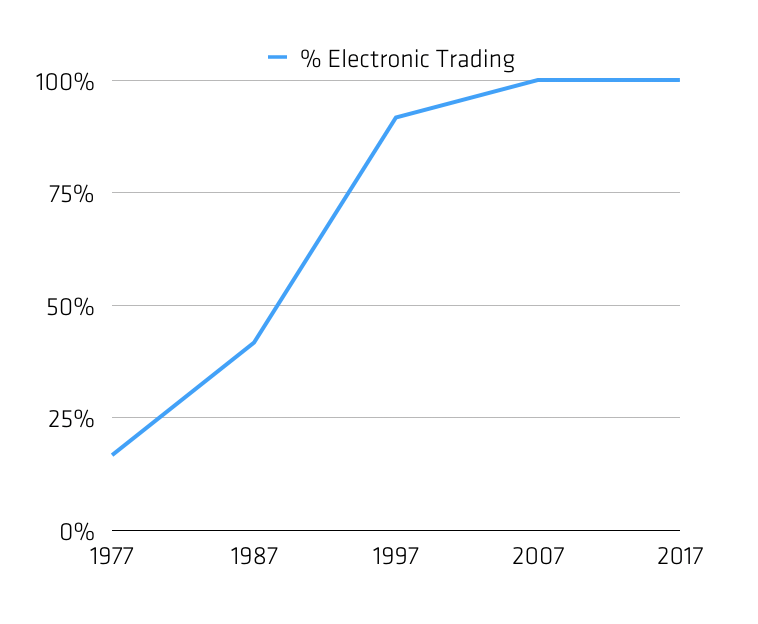

As a part of this mini-survey, we also looked at the shift in transaction volumes from physical trades to electronic ones. This became one of our proxies for the digitalisation of assets — the transition of exchange volumes from open outcry to electronic trades.

Open Outcry trading versus electronic — CoinShares Research

Open Outcry trading versus electronic — CoinShares Research

In a short amount of time, digitised, electronic trading accounted for more than 50% of all bids placed. By the early 2000s, open-outcry trading was effectively extinct.

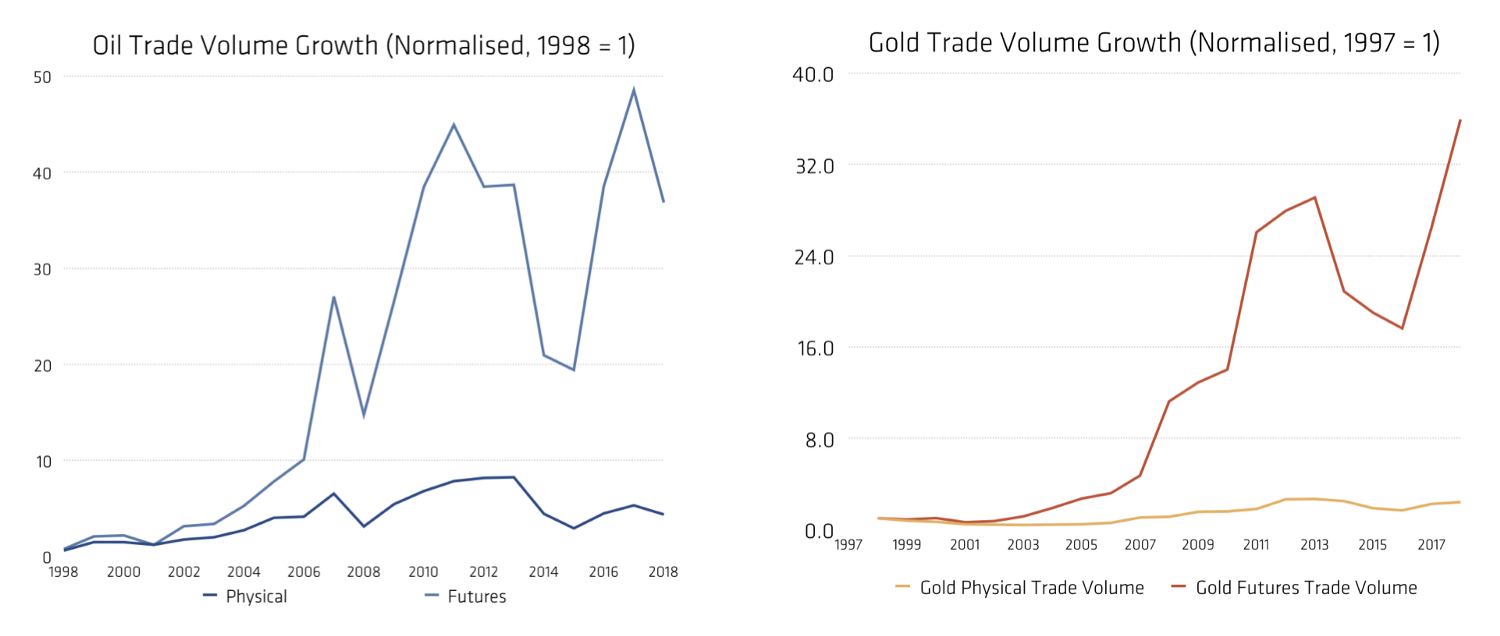

This same evolutionary phenomenon is particularly well illustrated by commodity trading, which saw a quick proliferation of interest in synthetic derivatives compared to the previously dominant physical volume. The below graphs show the relative growth in futures markets versus physical volumes for Gold and Oil.

Please note that while there are many Gold and Oil derivatives, we have used futures as a proxy to represent this digital shift. Had we included the market for Gold ETPs, this shift would be even harder to deny.

Please note that while there are many Gold and Oil derivatives, we have used futures as a proxy to represent this digital shift. Had we included the market for Gold ETPs, this shift would be even harder to deny.

Having plotted dependency and digitalisation on these axes, the changes between years is interesting to track (shown below from 1982–2017):

Representational Figures. CoinShares Research.

Representational Figures. CoinShares Research.

Throughout each phase of this trend, it seems that one asset leads, or paves the way, and others follow. I expect bitcoin’s emergence as a new type of asset, which lives in the top right quadrant, to have a similar effect and pull other assets in this direction as well.

I believe it is likely this will occur within the ‘second layer’ infrastructure that is being built on top of the bitcoin blockchain. There is already technology being deployed which facilitates ‘tokenisation’ of real-world assets, in a format compliant with existing regulations — as my business partner Danny Masters has touched on.

In the meantime, however, this category represents a tiny fraction of global assets, and in any case has clear potential for substantial growth.

So why does this matter?

Until Bitcoin was introduced, we never had a functional way to operate independently from this web of financial intermediaries in the digital sphere; no way to hedge against financial intermediaries in the same way that we could with our physical offline portfolio (e.g. physical gold, fine art, wine).

Before Bitcoin, digital investments always required a trusted third-party for settlement, clearing, and custody.

Bitcoin’s ‘why’ is that it removes the need for intermediaries and provides an alternative choice to the system — not simply a spiffy facade.

That choice is an evolutionof a trend which dates back over 35+ years now.

If we want consumers to consider adoption, we need to start thinking about how this fits in the larger context — bitcoin does not exist in a vacuum.

One of the most important features of Bitcoin is that it gives users the choice to hold a completely digital bearer asset, and manage the keys for themselves to eliminate counter-party risk.

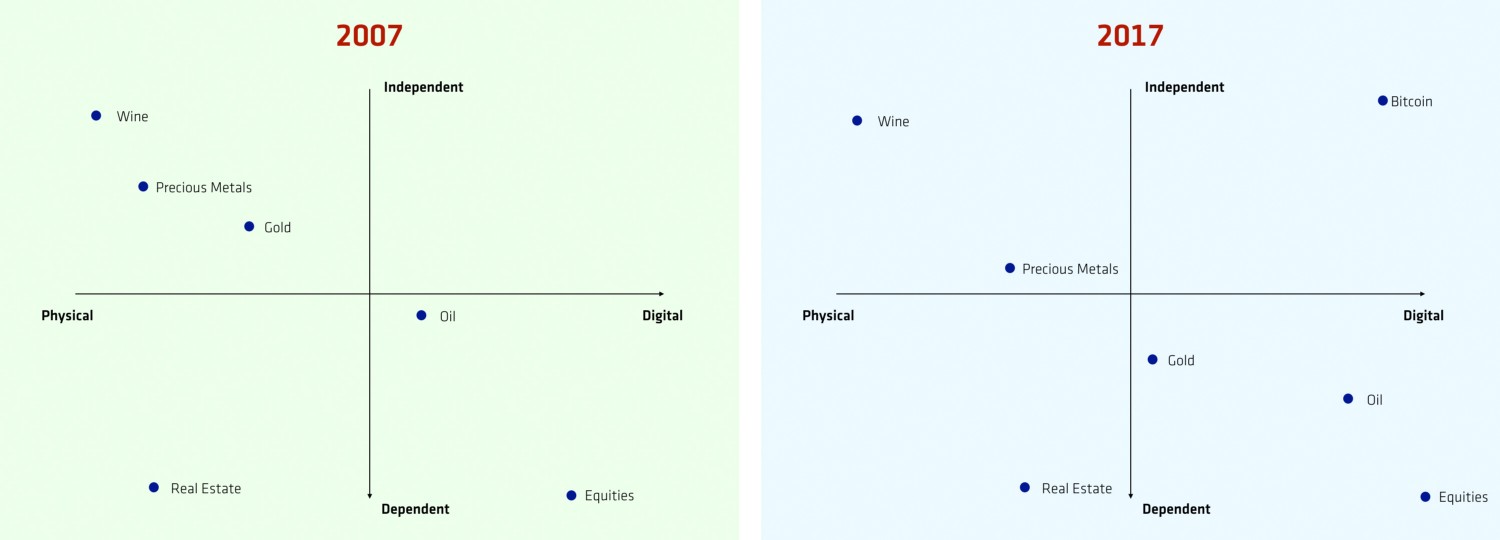

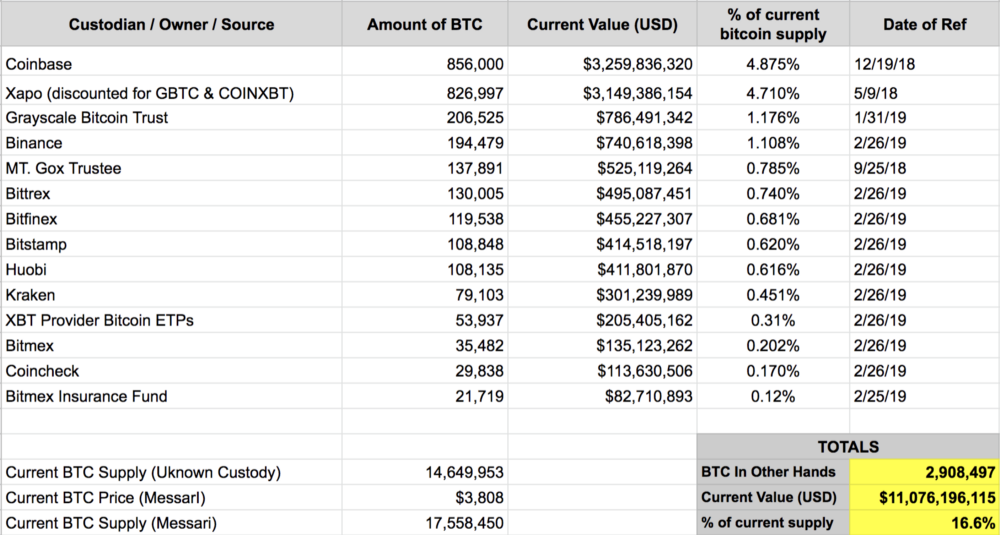

Don’t get me wrong — I still expect intermediaries, lots of them in fact.

The business I run on a daily basis acts as an intermediary, offering convenience and a familiar format (ETP) in exchange for control over the underlying assets the product track. Many exchanges offer a similar proposition, acting at least as a temporary custodian for customer funds.

The above table is only in regard to bitcoin holdings, not other crypto assets. Please feel free to drop a note in the comments of any products we may have missed. You can also view our full data and sources here.

The above table is only in regard to bitcoin holdings, not other crypto assets. Please feel free to drop a note in the comments of any products we may have missed. You can also view our full data and sources here.

A quick scan of the publicly reported bitcoin being held by an entity that is not the ultimate beneficial owner shows that at least 17% of the currently circulating bitcoin supply is likely custodied by a third-party.

Coinshares Research

Coinshares Research

Third-parties offer convenience, alleviate the hassle of key management and custody, and can streamline compliance requirements. Third-parties are not inherently good or bad; they simply offer a service to which users have grown accustomed.

But what is different about Bitcoin and this new digital paradigm is that these users finally have a choice. They have an option to utilise the convenience of these intermediaries, and the security trade-offs (risks) are clear.

In other words, with Bitcoin the risks are right there in front of you, and each individual has the opportunity to choose how much of that risk to take.

This is a huge leap forward in the evolutionary progression of our digital financial lives, especially when we consider the web of complexity and blind trust that consumers are required to place in our current financial system.

Personally, I could not be more excited for what comes next. But I’ll conclude by asking a favour…

Right now, too much of Bitcoin’s “viva la revolución” mantra feels like this:

Do us all a favour — help Bitcoin, and please STOP SCREAMING ANARCHY AND REVOLUTION. We might just help the world evolve — and drive bitcoin adoption — in the process…

Much credit to many members of the CoinShares team for the contributions, edits and comments — getting this right is always a team effort.