Beware of Lazy Research: Let’s Talk Electricity Waste & How Bitcoin Mining Can Power A Renewable Energy Renaissance

Beware of Lazy Research: Let’s Talk Electricity Waste & How Bitcoin Mining Can Power A Renewable Energy Renaissance

Bitcoin mining update — Part 2 of 2

By Christopher Bendiksen

Posted December 6, 2018

This is part 2 of a 2 part series

- Part 1 An Honest Explanation of Price, Hashrate & Bitcoin Mining Network Dynamics

- Part 2 Beware of Lazy Research: Let’s Talk Electricity Waste & How Bitcoin Mining Can Power A Renewable Energy Renaissance

If you’re reading this, then perhaps you’ve read the latest CoinShares Research report on the bitcoin mining network, my previous commentary on creation costs, or even better: both!

Or maybe you haven’t read either and came straight for the hot sauce.

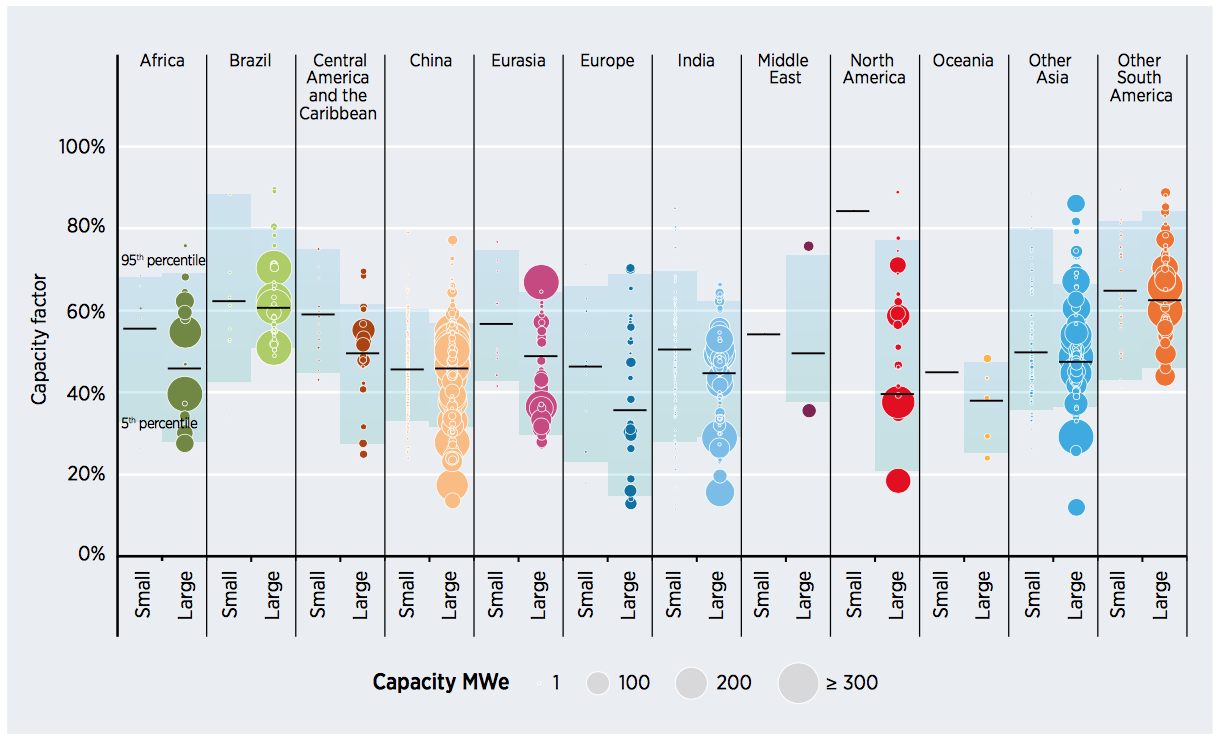

Either way, at this point you probably haven’t missed it: the hottest narrative in the anti-Bitcoin playbook is the environmentalist attack on Proof-of-Work (PoW) consensus algorithms. Exhibit A:

Oh dear…

Oh dear…

While it’s encouraging that Bitcoin detractors are clearly running out of ideas, it is nevertheless a powerful narrative — especially for younger generations whose future prosperity not only rests on the reintroduction of sound money, but also on a relatively benign global climate.

Thus we feel compelled to address this narrative with data and methodologies that hold up against both internal and external scrutiny. In our view, this is more than can be said for most (not all) of the research underpinning the narrative that we hope to debunk, once and for all.

Bitcoin is boiling the oceans!

You’ve surely heard it. Where did this idea originate?

As with many dubious claims, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that much of it is underpinned by a single, leisurely researched source: Digiconomist.

In fact you’d be hard pressed to find many articles in the press pushing the environmentalist, anti-PoW narrative that do not link back to that one source. But hey, can you really blame them in today’s sound bite media environment? Research is hard and time consuming.

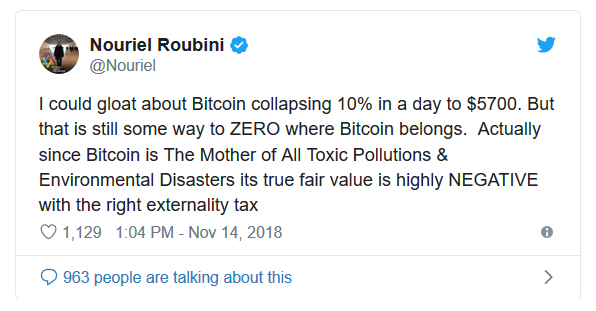

Without spending too much time on Digiconomist, I cannot avoid pointing out that within days of releasing our last mining report — which offered a more granular methodology for estimating the total power draw of bitcoin miners — and after being called out in no uncertain terms by Nic Carter on Twitter, the Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index on the website mysteriously flatlined even though the hashrate continued growing. Strange.

Screenshot of the Digiconomist website.

Screenshot of the Digiconomist website.

I also need to give some praise here though: it takes courage to admit you were wrong. I respect that.

For any journalists who happen to read this — please consider your sources before treating their unsubstantiated opinion as fact in your coverage!

The typical anti-PoW argument

So let’s reconstruct the environmentalist argument, which usually goes something like this:

A1 — Bitcoin mining is highly energy intensive.

A2 — The vast majority of bitcoin miners are located in China.

A3 — Bitcoin miners in China are mostly using dirty, coal-based power.

C1 — Bitcoin mining has a comparatively extreme carbon footprint.

C2 — Bitcoin is bad.

The first assumption is true, we all know that. It’s one of the fundamental reasons the Bitcoin network is so incredibly secure!

The second assumption used to be true, and is still not that far from the truth — but it’s inaccurate nonetheless. (For the sake of this post we’ll call it true, because it doesn’t really matter all that much.)

The third assumption however, is false, which ruins both conclusions.

How do we know that? Because unlike certain other frequently cited sources, we actually did the research. And to be clear, this was grueling, backbreaking research.

As of writing, we’ve now spent over a year getting to the bottom of this claim, and it wasn’t easy by any measure.

We’ve talked to everyone that would talk to us, and pestered those that wouldn’t. Rejections left and right. Our mining analyst Samuel Gibbons has trawled every forum, every message board, every channel, every press release, every public company release and every news article we could find. Some in English, many in Chinese.

So I completely understand the temptation to use hypothetical top-down assumptions for these calculations, I really do. Especially if it fits a certain narrative that one wants to push. I mean, if it looks like it could make sense, who would actually take the time to check, right?

Well, we did check and feel confident that this assumption has been soundly proven wrong. As such, we hope the assertiveness is scaled back a few notches while the methodologies are revisited and more work invested in the process.

And while we’re on the subject, we’ll be the first to admit — our results likely have significant error margins (although we chose to use assumptions that should place us at the conservative end of this margin and not the other way around). We would appreciate any additional efforts directed towards double- and triple-checking these conclusions.

Poor research — whether the result of lazy ignorance or outright dishonesty — works to everyone’s detriment. We need higher quality research in this space.

The reality of Bitcoin’s energy mix

Bitcoin mining is mainly driven by renewable energy — hydro (by far the largest component), solar, wind and geothermal. Period.

In fact, we’ve estimated the lower bound of renewables penetration in the bitcoin mining energy mix to be 77.6%.

We actually think it’s significantly higher than that, but in the name of defensible conservatism, we won’t say what that number is.

Everyone seriously involved in bitcoin mining already knows this — and has known for years — but it’s been surprisingly hard to quantify so we’ve kept our heads down in case we were all somehow wrong. The mining industry is notoriously secretive which makes it exceptionally tough to find or extract quality data.

So how’d we do it?

First, we decided to turn the commonly employed top-down methodology on its head and go bottom-up instead.

This means that instead of picking a single or couple mining units and using their specs as a proxy for the entire network — essentially pretending the entire network is simply a multiple of the same unit(s) — we went the other way around and figured out approximately how many units of each mining hardware exist in the current network .

Over the last year we painstakingly assembled a model of all mining gear produced in quantities exceeding 1000 units. We collected performance specs, volume weighted average purchase prices, batch sizes and total deployment numbers.

From that dataset we calculated that the bitcoin mining network currently draws approximately 4.7 GW, or 41tWh on an annualised basis.

At the time of writing, this figure is falling — and has been since late September. The estimate also includes a 20% excess for cooling, a figure we consider highly conservative.

For reference, there are approximately 85m PlayStation 4, 40m Xbox One and 15m Nintendo Wii U consoles distributed among global households (see our report for full list of sources). Their weighted average gameplay power draw is approximately 120W.

Assuming these gaming systems are played on a modern 40’’ LED TV drawing only 40W, for 4 hours a day, and idling for 20 hours a day, at a weighted average of 10W, they alone draw more power (4.9GW) than the entire bitcoin mining network.

This doesn’t even consider the renewables penetration in their energy mix, which assuming they are globally distributed, is a measly 18.2%.

As Dan Held would implore: somebody call the electricity police!

Here’s another one for ya.

Here’s another one for ya.

You were talking about renewables though?

I was indeed. This was a tough nut to crack. And while we searched and prayed for shortcuts to quantify the renewables penetration in the energy mix of miners, there is none. So we had to do it manually.

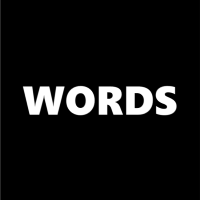

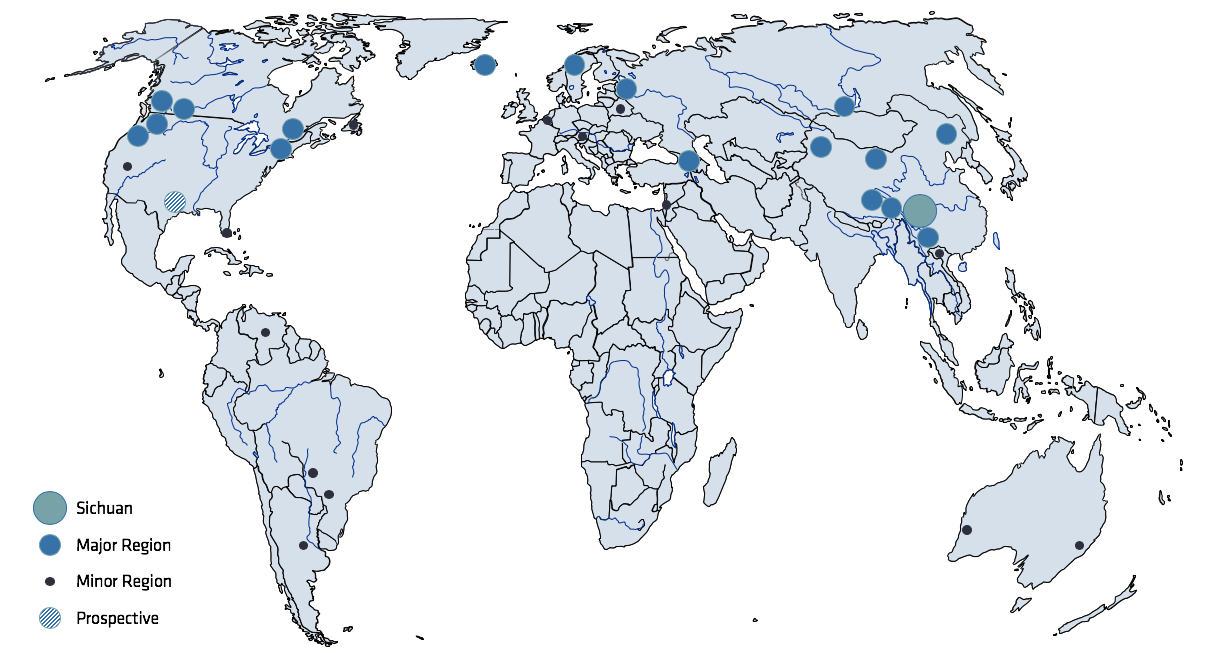

Over that same year, we also mapped out every relevant global mining region. The result looks like this (full source list in the report):

We then teamed up with some friends at Three Body Capital, who were able to source provincial-level curtailment rates and renewables penetrations in China. We combined this with publicly available renewables data for the non-Chinese regions and thus were able to arrive at a lower bound for the renewables penetration. What did we find?

Not only does the Bitcoin network consume much less power than its detractors claim, it is mainly driven by renewables — 77.6% lower bound versus global avg. of 18.2%

By inference, Bitcoin is therefore ‘cleaner’ than almost every other industry.

(I know I keep saying this, but for a full overview of our numbers and figures, please check out the paper itself)

Doesn’t this just displace other demand onto fossil electricity?

The short answer: for wind and solar, possibly — but this is only if miners that rely on them wish to mine 24/7 and are located in fossil-dependent regions(miners like that might exist, but are rare in the industry).

For hydro, this is much less of a concern. And here’s why:

In reality, there is really no clean separation between electricity sources on the grid. Overly simplified*, every producer contributes their production to the same grid, from which all demand is drawn.

(*Sidebar — this is not technically true as there are often incompatible and/or semi-isolated grids operating in areas that you would assume were economically integrated from an electricity standpoint)

Assuming this was the case for simplicity’s sake, then you could argue that Bitcoin simply displaces other competing demand onto fossil fuels.

While this may seem reasonable on the surface, in reality it is not so straightforward. The reasons for this are slightly complicated, but it roughly comes down to a matter of geography and physics.

I will restrict this discussion to hydro power as this is the largest component of global renewables generation and an even bigger component of Bitcoin mining. Most of this also applies to geothermal power which suffers from many of the same geographical issues as hydro.

Working with nature

Hydro power, while awesome, comes with the enormous drawback that you cannot build it wherever you want.

This should be obvious. The most productive hydropower is often found where there’s a combination of powerful rivers in mountainous terrain or highlands. Most humans, however, live in lowlands where it’s easier to grow food.

Fossil fuel power plants are therefore built close to the population centres they are intended to serve. Hydro plants, on the other hand, must be built where nature produces the prerequisite conditions to sustain them, which is often far away from demand centres.

This issue persists in China, the US, Siberia, Scandinavia, and Central South America: the best areas for hydro development is simply not where most people actually live.

For example, in the United States most hydro power is generated in — you guessed it — the mountains. More specifically, it is largely produced in the Columbia River basin of the Pacific North West, which according to the EIA, provided 44% of all hydroelectric power in the US in 2012.

Americans, however, do not tend to live in the mountains — they live predominantly on plains in California, around the Gulf of Mexico, Mississippi Basin and along the East Coast.

This causes a problem. You simply cannot transmit electricity from the Pacific Northwest to California, Texas, or the East Coast while maintaining the same cost profile.

Why not?

Whenever electricity is sent through a medium, electrical resistance will cause the medium to heat up while consuming some of the electrical power (unless the medium is a superconductor). This is how incandescent light bulbs and many electrical heaters work — it is also the reason your computer gets hot.

The EIA lists transmission losses for High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) lines at 3% per 1000 km, versus 7% per 1000 km for High Voltage Alternating Current (HVAC) lines.

HVAC is cheaper than HVDC and is normally used for short distances, whereas the latter is more expensive and used for longer distances. Lest you get the wrong idea though, they are both expensive, just one even more so than the other. Also, transmitting power over long distances often involves a bit of both.

HVDC lines act as ‘superhighways’ of power transmission and run along certain highly trafficked routes, while HVAC ‘access roads’ connect them to the wider region. Further driving up the cost — nobody wants them nearby. They’re ugly, and some people believe they cause all sorts of exotic pathological conditions.

The best locations for hydro plants are not necessarily well-connected to this transmission network—or even anywhere near it — and there are other factors limiting the economic viability of building new transmission lines such as mountain ranges or national parks. This makes remote power plants particularly vulnerable to transmission losses.

Transmission losses effectively increase the cost of electricity as you transport it away from its source.

Electricity prices can be seen as a spectrum, increasing as you move further away from its sources. The cheapest price is always right at the power plant, which is precisely why Bitcoin miners cluster as close to their sources as possible.

Stranded hydro

Often then, before hydro power can reach large population centres, transmission losses can make its price rise above that of competing fossil or nuclear power plants.

The net effect is that a significant amount of hydro power becomes stranded,meaning some of its potential output cannot be sent to demand centres while retaining a competitive price.

While this is unfortunate from an environmental standpoint, consumers tend to prefer cheap electricity to expensive electricity (for obvious reasons).

We can gain some insight to the overall usage of already installed hydro power plants by looking at their capacity factors._According to the International Renewable Energy Agency, global hydro capacity factors between 2010 and 2016 were 49%, meaning that global hydro plants _on average produced at less than half of their capacity.

Now this does not necessarily mean that out of the total global installed hydro power capacity of 1,121 GW, more than half is wasted (for comparison, remember that the Bitcoin network currently draws 4.7 GW, or 0.4% of that).

Plants may be built to accommodate variable daily demand peaking with human waking hours, or seasonal supply of water peaking with cyclical rainy seasons. This is also one of the reasons we chose to use annual net power produced — not installed capacity — in our calculations, as the latter skews the numbers in favour of renewables.

Wasted hydro

That being said, there are still multiple sources that do suggest that enormous amounts of hydro power is actually wasted (by simply letting water flow over the dams) every year.

The magnitude in China alone is staggering. According to Reuters, citing the provincial governor Ruan Chengfa, in Yunnan Province alone 30 TWh of hydro power is wasted every year. Again, the entire Bitcoin mining network draws an annualised approximate 41 TWh at current rates.

Things are not much better in neighbouring Sichuan — home of an estimated 42% of all Bitcoin hashpower — where another Reuters article explains that the province’s total hydro capacity of 75 GW (versus Bitcoin’s 4.7 GW draw), is more than double the capacity of its grid! The implication being that power on the order of hundreds of TWh are wasted every year.

By the way, if you’re curious how this economic quagmire came to be, first consider the information asymmetry between central planning committees and the distributed free market; then go read this excellent pieceby our colleagues at BitMEX Research.

But wait, there’s more

I’ll preface by saying that we have not been able to conclusively prove this thesis (yet), but it has been postulated by other researchers and deductive reasoning suggests it is indeed true.

While there is anecdotal evidence supporting it (sources in report) and we would prefer harder proof before we claim this to be conclusive, consider the following:

Because bitcoin mining is highly mobile compared to overall power demand, it might actually be a boon for global stranded renewables. Whereas traditional industrial and residential power demand is largely geographically captive — be it by proximity to cities, resources, transport links or whatever other factors determine the location of such entities — bitcoin mining can be undertaken pretty much anywhere.

As discussed above, nature-driven energy production is necessarily bound to where natural energy sources are located. Unlike fuel-based generation, they cannot be placed wherever demand is strongest and fuel can be sourced. This is important for two reasons.

- High voltage grids are expensive to construct, which means they are only economically viable if the size of the generating plant(s) is large enough. The farther away the power plant is, the more expensive the grid connection will be.

- Long-range energy transmission incurs losses for producers as a significant percentage of the electricity is lost to heat dissipation during grid transmission. This effect worsens with distance.

Combined, these two factors have a dampening effect on renewable energy development. Rivers, deserts and windy spots are where they are and cannot be moved. Building up renewables projects to the necessary scale required for grid connection is capital intensive and often prohibitively risky if unconnected to cornerstone demand.

This means that some of our most promising sources of renewable energy remain untapped due to their remote locations.

Again, this energy is effectively stranded.

We also see this problem in projects that are already built. For various reasons, many renewables projects today are significantly under-utilised. Most often because: (a) they are located far away from large demand centres; (b) previous cornerstone clients have moved or shut down; or (c) the anticipated demand never materialised as hoped.

These projects generate electricity supplies in excess of demand, which forces down the price of excess supply, especially immediately around the power plant .

Such projects act as magnets for bitcoin miners. Unlike traditional industries, bitcoin mining is highly mobile and both can and must move to wherever power is cheap. All miners need is an internet connection and roads in — almost all modern power generation developments have both.

Bitcoin mining can thus serve as the cornerstone demand for the lowest cost renewables, wherever they may be. This both reduces the need for government subsidies and increases profitability.

Increased profitability makes reinvestment more attractive, which in turn can increase the scale of projects. Larger scale projects may then enable grid connection.

As soon as these projects are connected to legacy industries or retail demand, they will tend to bid prices up closer to regular market prices and bitcoin miners will be forced to move on to the next project.

Bitcoin mining is a relentless race to the lowest electricity costs and therefore — as explored by Dan Held and Nic Carter — acts as an electricity buyer of last resort.

In this manner, bitcoin mining — which offers the possibility of immediate electricity monetisation independent of grid connection — can play a vital part in the renewables development cycle.

The Takeaways

- Contrary to what you’ve heard in the media, bitcoin mining is not an environmental disaster. In fact, it is one of the cleanest billion-dollar industries on the planet.

- The combined total bitcoin mining network draws less power than global gaming consoles running 4 hours per day.

- Bitcoin mining is mainly powered on renewable energy, at levels more than four times higher than the global average (>77.6% vs ~ 18.2%).

- Every year, enough hydro power is wasted in Yunnan and Sichuan alone to power the Bitcoin mining network many times over.

- Bitcoin miners are highly mobile and can therefore serve as cornerstone demand for low-cost stranded renewables.

- By increasing profitability and lowering reliance on subsidies, bitcoin mining can positively contribute to the development and scaling of renewable energy projects wherever conditions are the most favourable.

Disclaimer

Please note that this Blog Post is provided on the basis that the recipient accepts the following conditions relating to the provision of the same (including on behalf of their respective organisation).

This Blog Post does not contain or purport to be, financial promotion(s) of any kind.

This Blog Post does not contain reference to any of the investment products or services currently offered by members of the CoinShares Group.

Digital assets and related technologies can be extremely complicated. The digital sector has spawned concepts and nomenclature much of which is novel and can be difficult for even technically savvy individuals to thoroughly comprehend. The sector also evolves rapidly.

With increasing media attention on digital assets and related technologies, many of the concepts associated therewith (and the terms used to encapsulate them) are more likely to be encountered outside of the digital space. Although a term may become relatively well-known and in a relatively short timeframe, there is a danger that misunderstandings and misconceptions can take root relating to precisely what the concept behind the given term is.

The purpose of this Blog Post is to provide objective, educational and interesting commentary. This Blog Post is not directed at any particular person or group of persons. Although produced with reasonable care and skill, no representation should be taken as having been given that this Blog Post is an exhaustive analysis of all of the considerations which its subject matter may give rise to. This Blog Post fairly represents the opinions and sentiments of its author at the date of publishing but it should be noted that such opinions and sentiments may be revised from time to time, for example in light of experience and further developments, and the blog post may not necessarily be updated to reflect the same.

Nothing within this Blog Post constitutes investment, legal, tax or other advice. This Blog Post should not be used as the basis for any investment decision(s) which a reader thereof may be considering. Any potential investor in digital assets, even if experienced and affluent, is strongly recommended to seek independent financial advice upon the merits of the same in the context of their own unique circumstances.

This Blog Post is subject to copyright with all rights reserved.

Thanks to CoinShares.