The Bitcoin Lightning Network: A Technical Primer

The Bitcoin Lightning Network: A Technical Primer

By Joe Kendzicky

Posted June 5, 2018

TL;DR:

The Lightning Network is a protocol layer that seeks to provide instantaneous, trustless Bitcoin payments. In this article, I walk through the construction process for Lightning Channels and illustrate how multi-hop transfers are initiated. This article is the third piece in a multi-part series where I attempt to deep dive into notable cryptoasset projects.

Background

The Lightning Network is Layer 2 infrastructure built on top of the Bitcoin protocol, and hopes to increase transactional throughput. Bitcoin has a hardcoded upper bound limit on the number of transactions it can process. In traditional payment rails, ledgers are updated every few seconds and can achieve high degrees of scalability. These systems reach finality quickly and efficiently due to their centralized structure: clients_communicate directly with the _master server, who make ledger alterations in real time as notice is provided.

Image Source

Image Source

Bitcoin faces inherent challenges since the system utilizes distributed architecture. When new information needs to be appended to the ledger, that information must be redundantly pushed across every participating server inside the network. These servers must parse through the data and reach consensual agreement on which transactions they intend to accept and write to database, and which to reject. The difficulty in this scenario arises when multiple servers have conflicting views on transactional sequencing. Each node in the ecosystem maintains equivalent weight, so without top-down authority to establish a canonical vision, the system would eventually stall out if participating validators are unable to reach consensus.

Image Source

Image Source

Bitcoin introduces the concept of mining to guarantee network progression and prevent ledger fragmentation. Miners contribute computational power from specialized hardware to earn the right to propose ledger alterations during iteration rounds which occur roughly every 10 minutes. A mathematical challenge is included in each round. If a miner is able to find a solution, they earn the right to establish canonical vision of the ledger, which the rest of the network accepts based off protocol rules. When a claimant proposes a solution, other nodes can verify integrity of the solution. Peers will only recognize the claimant’s ledger version if the solution is valid.

When we talk about “vision” of the ledger, we are referring to the construction of blocks. Blocks are aggregations of transactions compressed into a singular file unit. When a miner “solves” a block, they earn the right to inscribe their view of the ledger to the blockchain, an immutable database containing an archive of previous network transactions. Transactions are simply lines of code, so they have deterministic size. With the blocks having an upper bound limit at 1MB, the system can process ~7 transactions per second (tps). In contrast, networks like VISA can support ~50,000 tps.

Overview

The Lightning Network utilizes the concept of payment channels to provide bi-directional monetary transfers, and envisions a network with near-instantaneous speed, zero counterparty risk, and low fees. In doing so, the Lightning Network aims to alleviate scalability concerns surrounding the Bitcoin protocol. The system routes around the bottlenecks of universal consensus by settling transactions off chain, avoiding latency and computational redundancies that plague blockchains. Lightning claims transactional processing capabilities in the millions of tps.

Funding Payment Channel

The first step involves an initial funding transaction where each party deposits BTC into a 2-of-2 multisignature address. Once deposited, each participant has full guarantee of security, since any forward movement of funds will require signature authentication from both parties. But what if the channel is unable to progress forward after the funding transaction? If the opposing party becomes unresponsive or loses their private key, any balance locked up in that channel is permanently lost. Thus, both sides of the agreement need insurance against counterparty risk that may ensue.

To solve this dilemma, users draft refund transactions and have their counterparty sign. These transactions are constructed before either individual deposit to the multisignature address, and allows for revocation of the original funds back to channel depositors. Bob asks Alice to draft a settlement transaction that refunds his deposit back to himself. Alice complies with the request, drafts the message, and signs it with her key. She then returns it to Bob. In the process, she also includes a similar refund script for her bitcoins. Bob reviews the transaction, and if the outputs align with his specifications, attaches his signature to the message, relaying it back to Alice. Both members now possess a symmetric transaction which they tuck away as leverage for a future mishap. In the event either party becomes unresponsive, the counterparty can simply broadcast the transaction to the network, creating an escape route to withdrawal their balance from the multisig. Both individuals are now protected and can deposit to the channel with full reassurance.

Commitment Advances

With funds locked up in the multisig account, a “channel” is now created. Participants can issue fully valid transaction scripts to one another via private medium, and both parties can accept these instruments of payment as valid without having to broadcast the payment on-chain. In doing so, these commitments act as a form of promissory note with enforceable guarantees backed by the Bitcoin blockchain, all while avoiding the bottlenecks and costs of universal consensus. If circumstance requires, either party can push the latest commitment version to the blockchain and close out the channel without requiring approval from their counterparty.

Problems arise when it becomes economically advantageous for a participant to push a previous commitment to the blockchain. Returning to our example, after both depositing a 1 BTC balance, Bob sends 0.5 BTC to Alice inside the channel. His balance will now show 0.5 BTC, and Alice’s will read 1.5 BTC. But remember, Bob has his initial refund TX, signed by Alice, that allocates 1 BTC back to himself. Bob is now incentivized to push this outdated transaction to the network and make off with Alice’s money. Thus, we need some method to invalidate previous commitments.

Commitment Transactions

When Bob and Alice want to advance the state of the channel, they need a way to autonomously enforce their contracts. This is done through commitment transactions. Suppose Bob wishes to send Alice 0.5 BTC. Each party creates two near-identical transactions spending the same input values. These transactions operate similar to a RBF or a Doublespend- if both transactions are pushed to the blockchain, only one of them will ultimately confirm and be appended to the ledger since they reference the same input values. Bob and Alice carefully construct these transactions in a manner that makes it deterministically provable which will be included into a block first.

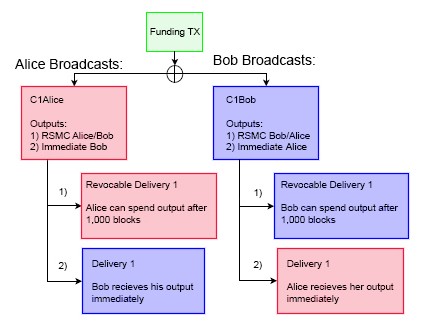

Bob creates a transaction by referencing a set of outputs, and signs with his key. We call this transaction C1Bob (Commitment1Bob), which he forwards to Alice. Alice mirrors this action, creating C1Alice and forwards to Bob. Because these transactions are originating from the 2-of-2 multisig, neither party’s script is valid until both signatures are transcribed. Once Bob and Alice put their stamp of approval on each other’s commitments, they are voluntarily accepting the potential of their counterparty broadcast the transaction at any point in the future (thereby closing the channel). Bob cannot push the transaction he constructed to the network, since he doesn’t possess Alice’s private key. Bob can only broadcast Alice’s version, and Alice can only broadcast Bob’s.

The above illustration describes the redemption paths if a commitment were broadcast on-chain. If Alice were to push her transaction to the network, she would initiate two events. The first would immediately unlock Bob’s balance, allowing him to transfer his funds. The second would trigger a countdown on her funds. Alice will have to wait 1,000 blocks in order for her outputs to unlock. Once this timespan has elapsed, her funds will become available for redemption. This process is mirrored on Bob’s commitment. If he pushes his version to the network, Alice’s funds are immediately unlocked, while he has to wait 1,000 blocks. These lockup intervals are set to mitigate counterparty risk.

We introduce the concept of Revocable Sequence Maturity Contracts (RSMC) as a means to invalidate previous commitments. This occurs via the scripting flag CHECKSEQUENCEVERIFY (CSV). CSV’s are a way to dynamically lock up bitcoins over a predefined time interval, and is enforced by the Bitcoin blockchain rather than users themselves. CSV checks for the current block height (aka the sequence) from the moment the transaction is included in a block, and verifies_that the encumbrance scripts are met. In the example above, it is the CSV encumbrance in the transaction that forces Alice/Bob to wait 1,000 blocks for their funds to become redeemable. This creates a _bonded deposit window where a plaintiff can present a breached remedy tool in the event the counterparty tries to broadcast an outdated commitment.

Creating Breached Remedy Commitments

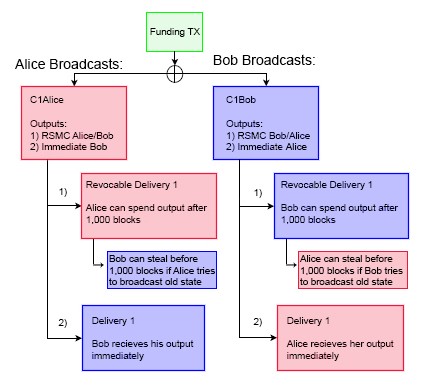

When Bob and Alice want to advance the state of the channel, they need a way to invalidate previous commitments. Bob and Alice repeat the commitment process by constructing a new 2-of-2 multisig account (aka C2Bob, C2Alice) with a fresh set of keys. They reference their outputs, enact similar 1,000 block CSV scripts, sign the transaction with their own keys and pass along to their counterparty. Their counterparty tucks this transaction away. However, before finalizing the new C2Bob/C2Alice commitment schemes, both parties disclose their private keys used in C1Bob/C1Alice. Once this occurs, each party is protected from publication of outdated commitments.

As mentioned earlier, if Bob closes out the channel, Alice’s funds are immediately spendable. Bob’s money on the other hand is locked up for 1,000 blocks by the CSV encumbrance. If Bob tries to cheat the system by broadcasting an outdated commitment whenever financially incentivizing to do so, those funds are not immediately accessible. Alice will see that Bob is trying to cheat her, and use her breach remedy “tool”. This tool allows Alice to spend the 1,000 block encumbered funds immediately if she can provide Bob’s private key. Alice is capable of fulfilling this obligation now that the channel state has advanced, because Bob has voluntarily relinquished the key to her in the last round. Thus, Alice can not only ensure that she won’t be cheated out of the BTC she is owed, but will be able to walk away with the entirety of Bob’s balance, making additional money. Thus, Bob is highly incentivized not to try and cheat the system by publishing outdated commitments, since Alice will be able to walk with his entire deposit. Conversely, if Alice tries to pull a similar trick on Bob, he can walk with the entirety of her deposit. This creates incentive models where both parties are highly incentivized to act altruistically.

Cooperative Channel Closeout

When either party wants to close out the channel, they can do so cooperatively by disregarding all outstanding promissory notes and constructing a normal transaction from the original 2-of-2 escrow. This transaction would pay out the respective balance to each member, based off the most recent commitments. Because the outstanding promissory notes are backed with full guarantee by the blockchain, both parties have an incentive to collaborate. Neither individual has to go through the frictionary process of paying additional on-chain fees, nor lose out on opportunity costs of time having their BTC locked up by the CSV encumbrances for 1,000 blocks.

Hashed Timelock Contracts (HTLC’s) and Multi-hop Transfers

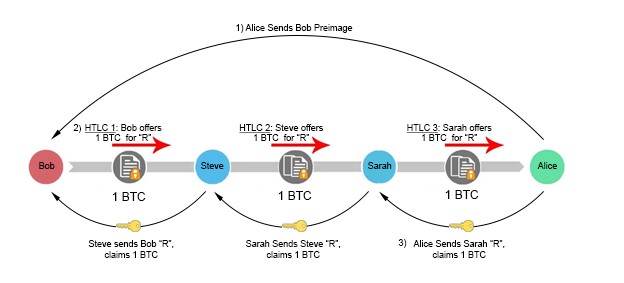

HTLC’s are forms of transactional encumbrances which use hashlocks (locking scripts that ensure certain data is known) and timelocks (restricts future spending of outputs until a predetermined date) as a way to enforce provisions on a transaction. Both types of encumbrances are enforced by the blockchain rather than channel counterparties. The concept is fairly simple, and serves as a way to extend payment channels beyond a bi-directional state. Lightning Network will have the ability to route channels deterministically through multiple parties through a process called multi-hop transfers. At first, Lightning might not be very appealing unless two participants plan to remunerate very frequently, since opening a new channel requires locking up assets via an on-chain broadcasted transaction. Bob having unique channels with many participants means less money in his wallet for discretionary spending, significantly reducing the versatility of his funds. Lightning alleviates these concerns by introducing an effective path finding algorithm between network participants, and linking their channels together via HTLC’s. Bob and Alice are two individuals who want to transact, but don’t have an existing channel open. If both parties have a mutual channel connection with Steve, they can still route the transaction with full guarantee of atomic settlement. This works by Bob paying Steve, who in turn pays Alice. Bob has now trustlessly paid Alice without needing to open a channel with her. If the relationships between participants are extremely isolated, we can keep introducing more intermediaries to form a lineage robust enough to facilitate payments.

Bob(the sender) initiates the multi-hop process by communicating directly with Alice(the beneficiary). Bobs asks Alice to create a randomly generated secret R, which remains private to Alice. Bob asks Alice for a hash of R, called the preimage, but not the plaintext version of R itself. Bob subsequently specifies only to disclose R to an intermediary party, Steve, in exchange for 1 BTC.

So, Alice hashes R, and sends a copy of the preimage to Bob. Bob takes this preimage to Steve, and offers a 1 BTC bounty if he can produce the hash’s plaintext version, R. Steve accepts the offer, and goes to Alice with an offering of 1 BTC in exchange for the secret value. Note that in this situation, Steve front runs his own capital to make this exchange with Alice. Alice, seeing this offer of 1 BTC in exchange for an arbitrary secret R, accepts the proposition and gives the value of R to Steve, just as she was instructed earlier by Bob. Steve then hands R to Bob in order to claim his bounty. In this example, Bob has found a trustless way to pay Alice, without having to go through the burden of opening a channel with her. If Bob and Alice lack a mutual contact to route the channel through, we can keep introducing more intermediary liquidity providers until a connection is made. For example, if Bob has an open channel with Steve, and Alice has an open channel with Sarah, and Sarah and Steve have a channel together, a payment can be initiated.

CHECKLOCKTIMEVERIFY (CLTV) vs. CHECKSEQUENCEVERIFY (CSV)

What is the difference between a CLTV and a CSV? Both are examples of timelock encumbrances, and are used to accomplish similar goals.

Suppose a CLTV encumbrance is placed on an output for 10 blocks. The current BTC block height is b=500,000. Once the blockchain hits b=500,010 the outputs unlock and become spendable. The time at which the original transaction gets a confirmation is irrelevant to the spender.

In contrast, a CSV script is based entirely on the time the original transaction is included into a block. Suppose a CSV script is placed on an output for 10 blocks. The current BTC block is b= 500,000. Once this transaction is broadcast, it sits unconfirmed for 5 blocks. After 5 blocks ensue, it finally gets picked up and included at b=500,005. In this scenario, the timer begins once that transaction gets its first confirmation. The CSV encumbered output doesn’t become spendable until 10 subsequent blocks at b=500,015. Conversely, if the original transaction receives its first confirmation at b=500,003 then the outputs becomes spendable at b=500,013.

In summary, a CSV sets a dynamic encumbrance that makes an output spendable after a specified number of confirmations once the original transaction is included in a block. In contrast, with CLTV you are specifying when the output will become spendable based off block height. This means that the output’s encumbrance status is completely independent of the mining process.

Constructing Hashed Timelock Contracts

In our previous example, we presented a basic overview of how a multihop transfer can occur, but failed to articulate how to create an enforceable contract on the blockchain to facilitate those functions. For example, what if Alice fails to produce the secret value after Bob transfers her the bitcoin? Or what if Bob revokes his bounty commitment to Steve after acquiring the secret from Alice? In both scenarios, Steve has lost money.

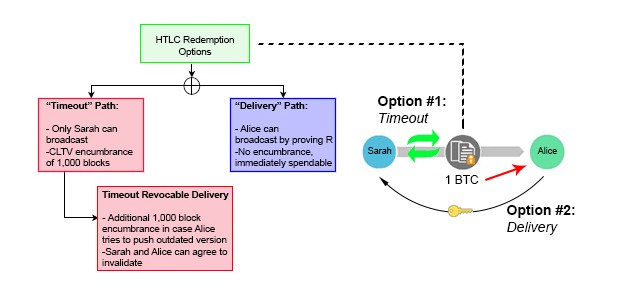

In order to create a trustless layer of commitments, we build off similar RSMC properties outlined in earlier sections, but add a few twists. After Bob communicates directly with Alice and receives a copy of her preimage, he constructs a hashed-timelock contract (HTLC) transaction with Steve. This contract has two paths for output redemption. The first is a “delivery” path which sends Steve 1 BTC immediately if he can produce the secret R. The second is a “timeout” path which allows Bob to refund himself in the event Steve cannot produce the secret. This is accomplished using a CLTV flag instead of the CSV as in previous examples.

In the transactional script, Bob sets the timeout length of the CTLV to 1,000 blocks. This means Steve essentially has 1,000 blocks to obtain R from Alice and claim the 1 BTC bounty via the “delivery” path. If he waits longer than this time, he loses guaranteed insurance that he can claim the bounty safely. Steve mirrors this same transactional script with Alice, front running his own personal capital in the process. If Alice wants to claim the 1 BTC sitting in escrow, all she needs to do is reveal the secret R. Once Steve has R, he can turn around and use it to pull the 1 BTC out of escrow sitting between him and Bob. Everyone gets paid.

Importantly though, these “timeout” intervals must decrease in length as the chain progresses right to left. The timeout between Alice and Steve must expire earlier than the timeout between Steve and Bob. If they expire simultaneously, Bob runs the risk of transferring his funds to Alice near the end of expiration, and then having Bob’s “timeout” unlocking before he has time to grab his funds out of escrow. In this scenario, Steve would be left doing the bagholding, since he front ran capital to Alice but was not able to collect from Bob. To make matters even more challenging, blocks are solved in random 10-minute intervals. There is no inherent guarantee that a subsequent block will be solved 10 minutes after a previous. It could happen 1 second afterward. This is why CLTVs are used instead of CSVs. Thus, it is imperative that participants provide ample blocks between channel “timeouts” to prevent loss of funds.

If Steve cannot obtain R from Alice (she is a fraudulent actor, becomes unresponsive etc.), nothing is hurt. He simply lets the channel expire and revokes his money out of the escrow by using the “timeout” path. This will set off a chain reaction, where Bob will revoke his funds out of escrow once they timeout. Though the parties may experience opportunity costs of locked-up capital, they have full reassurance that they can ultimately reclaim those escrowed funds.

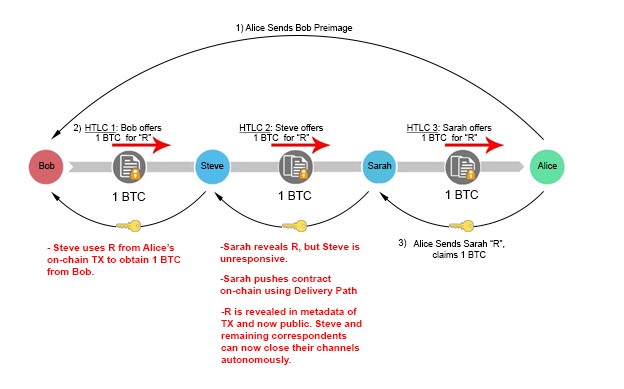

Interestingly, disruption of the channel somewhere along the line does not destroy payment guarantee, but actually strengthens it. Suppose Sarah fulfills her end of the obligation and provides Steve with R, but Steve remains unresponsive and does not update their channel balance. In such a situation, Sarah is still capable of obtaining the 1 BTC she is owed through the HTLC contract. If Sarah uses the “Delivery” Path, R becomes publicly available on the blockchain; she has to disclose it in the metadata of the transaction to unlock the encumbrance and receive her BTC. Intermediary liquidity providers can extract this information off the blockchain and use it to unlock their escrow channels immediately, without ever having to wait for their correspondent to reveal R to them. This structure provides cryptographic certainty that each claimant will be able to receive their capital, so long as they push the TX before the CLTV encumbrance expires.

Recap

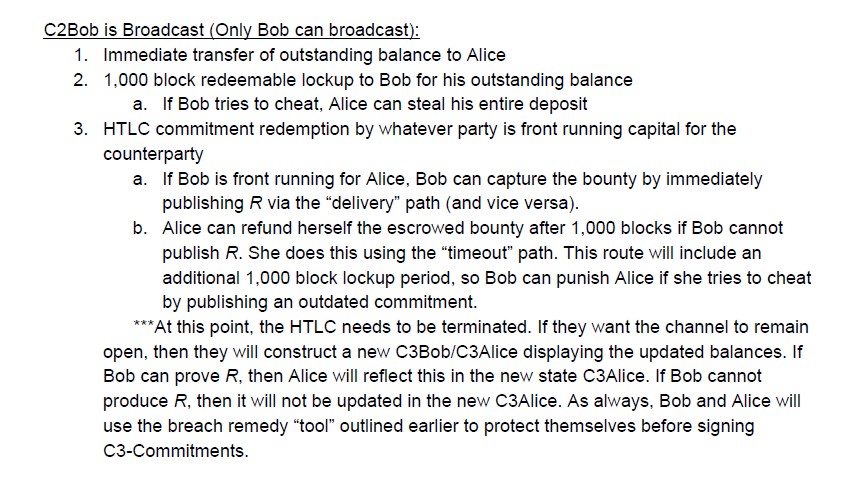

Sequence of events for a C2Bob broadcast

Sequence of events for a C2Bob broadcast

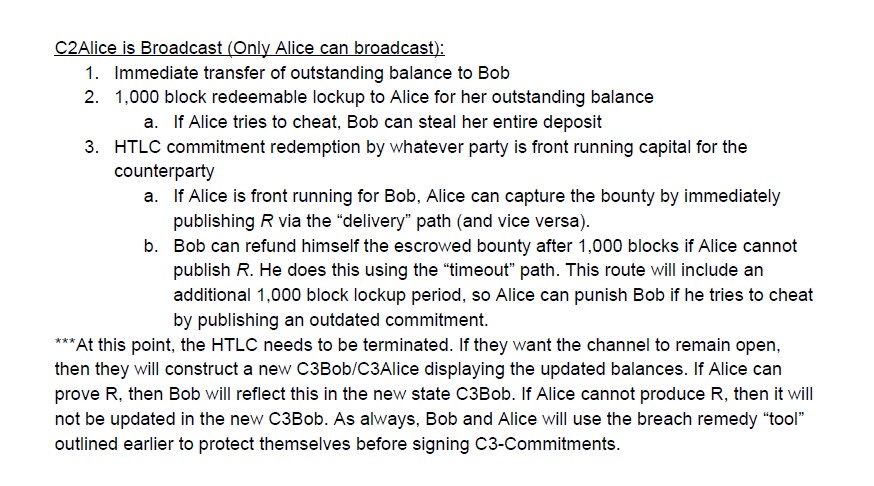

Sequence of events for a C2Alice broadcast

Sequence of events for a C2Alice broadcast

Final Closeout

The beautiful thing about Lightning Network is that all these described provisions will rarely take place on-chain. Participants can avoid broadcast of all these intermediary steps and simply pay one another out at the conclusion of the channel using traditional payment terms. These intermediary technicalities exist for the sole purpose of protection. Participants essentially load a gun, then handing it over to the opposing channel member with instructions to shoot if they act dishonestly. Incentives are aligned to follow the rules by constructing channel operations in such a manner. Thus, altruistic behavior is a rational assumption. If participants act dishonestly or become disconnected for extended periods, the Bitcoin blockchain acts as an enforcement mechanism to ensure integrity of commitment balances.

Follow me on twitter for more Crypto insight!