On Bitcoin’s Academic Lineage

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

On Bitcoin’s Academic Lineage

By ElSeidy

Posted March 22, 2019

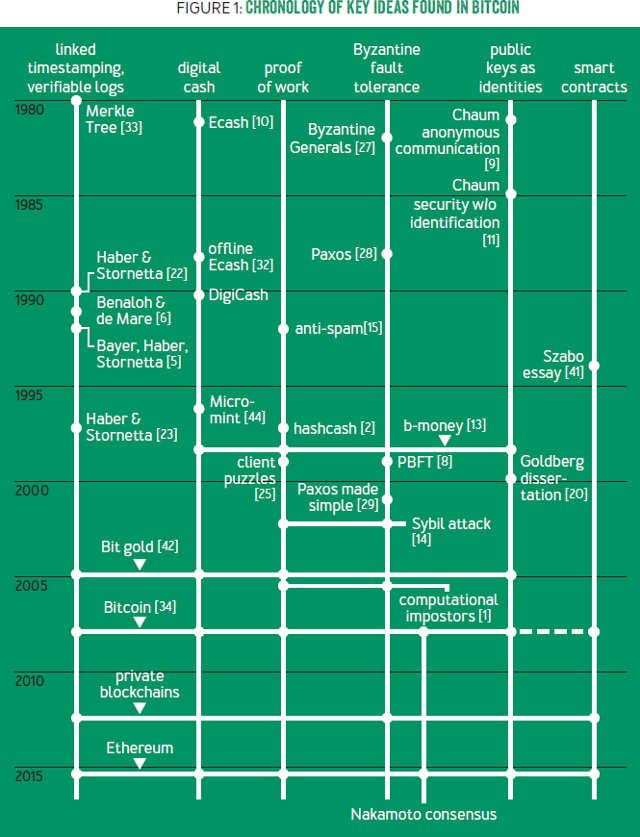

Stiglers law of eponymy states that no scientific discovery is named after its original discoverer. For example, the pythagorean theorem was well known to the Babyolnians much before Pythagoras. Other examples include Hubble’s law, Haley’s comet, and Stigler’s law itself — being self-referential. It comes as no surprise that Bitcoin is no different. There is a common misconception that Bitcoin bears no resemblance to earlier academic work. Prof. Arvind Narayanan, from Princeton university, challenges this view, in his published article named “ _ Bitcoin’s Academic Pedigree_ “. He shows that almost all of the technical components of Bitcoin originates from the academic literature of the 80s and 90s. This is not to diminish Nakamoto’s contribution but to turn attention towards the fact that they stood on the shoulders of giants. Nakamoto’s genius was in the intricate way they assembled the components together into a resilient and secure system. Narayanan’s positioning of Bitcoin within academic literature helps us appreciate its novelty in the right dimension.

Bitcoin’s intellectual history also serves as a case study demonstrating the relationships among academia, outside researchers, and practitioners, and offers lessons on how these groups can benefit from one another. In this article we summarize the main points from Narayanan’s article and conclude with a set of lessons learned.

Chronology of key ideas found in Bitcoin. Image taken from Bitcoin’s Academic Pedigree.

Chronology of key ideas found in Bitcoin. Image taken from Bitcoin’s Academic Pedigree.

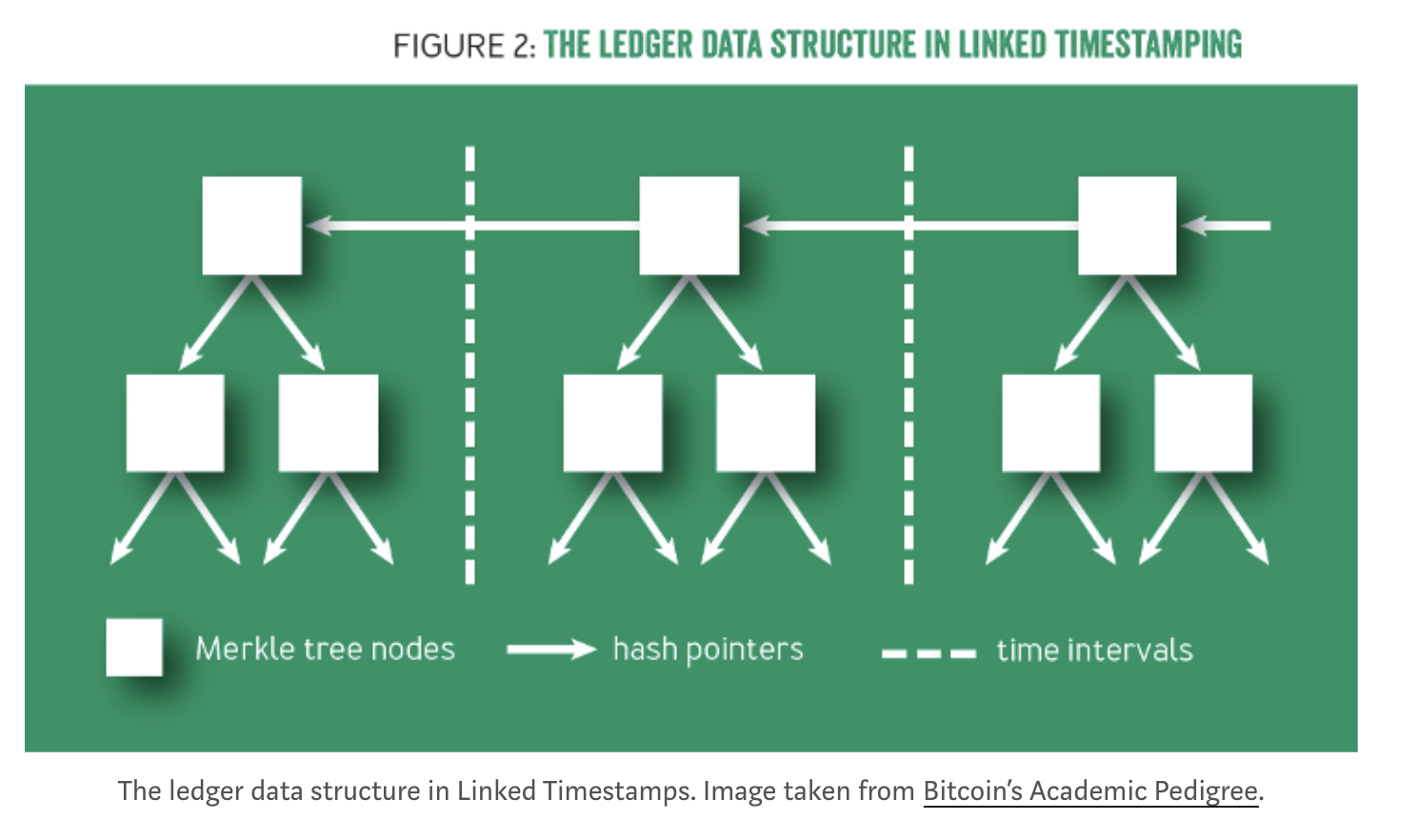

The ledger

The public ledger is the most fundamental component of Bitcoin. To understand Bitcoin’s history, we first need to understand the ledger. It is where all transaction records are saved and trusted by all system participants. Bitcoin converts this system for recording payments into a currency. The ledger, as a datastructure, should be a) immutable, meaning that its historical state can never be changed, and should be able to b) obtain a succinct cryptographic digest of the ledger-state at any time, and have a c) consistent global view across all distributed nodes.

Linked Timestamping

Bitcoin’s ledger data structure is borrowed from a series of papers by Stuart Haber and Scott Stornetta written between years 90-97. Their work addressed the problem of document timestamping as they aimed to build a “digital notary” service. Their abstraction of a document is quite general and could be of any data type. They mention financial transactions as a potential application, but it wasn’t their focus.

In their design, documents are constantly being created and broadcast. The creator of each document declares a creation timestamp and signs both, the current document and the previously broadcast document. This previous document has signed its own predecessor as well, thereby, creating a long chain of documents with pointers backwards in time. This chain-signing property is essential to provide the immutability properties of the datastructure. As followup to their initial work, they introduced other ideas that make this data structure more effective and efficient:

-

Hashes: Documents are interlinked with each other using hashes rather than signatures as hashes are simpler and faster to compute.

-

Batching: Instead of chaining individual documents, one can group them into batches or blocks such that all documents within a block have the same timestamp.

-

Indexing: Within each block, rather than representing the documents using a linear chain, one can link them together using a binary tree of hash pointers, called a Merkle tree.

Clearly, if you replace documents with transactions, this design resembles bitcoin to a great extent. Nakamoto cites Stuart and Scott’s work in his original paper.

Merkle Trees

As mentioned earlier, it is more efficient to represent blocks using trees rather than a linear-chain. Abstractly, each block is represented as a Merkle tree, where the leaf nodes are transactions, and internal nodes consist of two pointers pointing to its children and a digest computed by their hashes as depicted in Fig. x. This data structure has two important properties:

- The hash of the latest block acts as a b)digest. Any small change to any of the transactions will have a rippling effect all the way to the root of the current block, and the roots of all following blocks. Therefore, knowing the latest hash is sufficient to download a verified ledger from untrusted sources.

- Another important property is the ability to efficiently prove that a particular transaction is included in the ledger. This is a highly desirable property for performance and scalability reasons.

Merkle trees have been around long before. They are named after Ralph Merkle, a pioneer in asymmetric cryptography who proposed the idea in his 1980 paper. By cryptographic standards, this idea is ancient, but its power has been appreciated since late.

Bitcoin may be the most well-known real-world instantiation of Haber and Stornetta’s data structures, but it is not the first. For example, Guardtime started offering document timestamping services in 2007.

Consensus & Byzantine Fault Tolerance

Another important requirement for public ledgers is to achieve a consistent transaction (or block) ordering across all nodes. Consensus across all nodes about state-consistency is inevitable for the ledger, or else, the collective ledger can spawn to different chain-forks. Linked timestamping alone is not enough to resolve forks.

A different research field called, fault-tolerant distributed computing, has studied this problem for decades. Generally speaking, the solution to this problem is one that enables a set of nodes to adopt the same state/transaction transitions in the same order. The particular order doesn’t matter as much as the consistent view across all nodes.

Early solutions, including Paxos, proposed by Turing Award winner Leslie Lamport in 1989 had constraints on the definition of faulty nodes. A prolific literature followed with more adverse definitions. The definition of faulty was generalized to handle any deviation from the protocol. Such Byzantine faults includes both naturally and maliciously occurring faults. In 1999, a landmark paper by Miguel Castro and Barbara Liskov introduced PBFT which accommodated both Byzantine faults and unreliable networks.

The literature of fault tolerance is huge and encompasses hundreds of variants and optimizations of Paxos, PBFT, and other seminal protocols. Nakamoto does not cite this literature or use its language in his original white paper. This is in stark contrast to linked timestamping. However, all of this work makes assumptions about the definition of honest nodes as being procotol-compliant behavior among a subset of participants. On the other hand, Nakamoto suggests that it is not necessary to blindly assume honest behavior because it is incentivized. A richer Nakamoto consensus analysis that takes into account the role of incentives does not fit cleanly into past fault-tolerant systems models.

Proof of Work

Nearly all fault-tolerant systems assume that most nodes in the system, e.g. 50 percent, are both honest and reliable. Nodes freely join and leave in an open P2P network. An adversary can therefore create enough nodes to overcome the system’s consensus guarantees. John Douceur formalized the attack on Sybil in 2002 turning to a cryptographic construction, called proof of work to mitigate it. A large segment of the Bitcoin community has the misconception that Nakamoto invented proof of work. The first proposal that could be called PoW today was created in 1992 by Cynthia Dwork and Moni Naor. Their aim was to deter spam by forcing email recipients to process only those emails that were accompanied by evidence that a moderate amount of computational work had been performed by the sender-hence, “proof of work.”

Hashcash

In 1997, Adam Back, a postdoctoral researcher at the time who was part of the cypherpunk community, invented a very similar idea called hashcash. Hashcash is much simpler than the idea of Dwork and Naor, because it uses hash functions. It is based on a simple principle: a hash function acts as a random function, which means that the only way to find an input that hashes a particular output is to try different inputs until the desired output is produced. As the name suggests, proof of work in hashcash was seen as a form of cash. However, the design of hashcash has no protection from double spending.

Incidentally, only in 1999 was the term work proof coined in a paper by Markus Jakobsson and Ari Juels, which also includes a nice survey of the work up to that point.

Digital Cash

Proof of work did not succeed as an anti-spam measure. One possible reason is the dramatic difference in the puzzle-solving speed of different devices. That means spammers can make a small investment in custom hardware to increase their spam rate by orders of magnitude.

In economics, the natural response to an asymmetry in the cost of production is trade — that is, a market for proof-of-work solutions. But this presents a paradoxical situation, because that would require a working digital currency. Indeed, the lack of such a currency is a major part of the motivation for proof of work in the first place. As hashcash tries to do, one crude solution to this problem is to declare puzzle solutions as cash. More coherent approaches to treating puzzle solutions as cash are found in two essays that preceded bitcoin, describing ideas called b-money and Nick Szabo’s bit gold respectively. However, if there is disagreement between servers or nodes about the ledger, there is no clear way to resolve it. These mechanisms are not very secure because of the Sybil problem.

Bitcoin

Understanding all these predecessors that contain pieces of bitcoin’s design leads to an appreciation of the true genius of Nakamoto’s innovation. In bitcoin, for the first time, puzzle solutions don’t represent cash by themselves. on the contrary, they are merely used to secure the ledger. Solving proof of work is performed by specialized entities called miners.

A miner who contributes a block is rewarded with newly minted units of the currency in exchange for the service of maintaining the ledger,whereas malicious activity is penalized. In this way, miners ensure each other’s compliance with the protocol due to the monetary incentives.

Bitcoin neatly avoids the double-spending problem plaguing proof-of-work-as-cash schemes because it avoids puzzle solutions themselves having value. In fact, puzzle solutions are decoupled twice from the economic value: the amount of work needed to produce a block in proportion to the global mining power, and the number of bitcoins issued per block.

Nakamoto’s genius, then, wasn’t any of the individual components of bitcoin, but rather the intricate way in which they fit together to breathe life into the system. The timestamping and Byzantine agreement researchers didn’t hit upon the idea of incentivizing nodes to be honest, nor, until 2005, of using proof of work to do away with identities. Conversely, the authors of hashcash, b-money, and bit gold didn’t incorporate the idea of a consensus algorithm to prevent double spending. In bitcoin, a secure ledger is necessary to prevent double spending and thus ensure that the currency has value. A valuable currency is necessary to reward miners. In turn, strength of mining power is necessary to secure the ledger. Without it, an adversary could amass more than 50 percent of the global mining power and thereby be able to generate blocks faster than the rest of the network, double-spend transactions, and effectively rewrite history, overrunning the system. Thus, bitcoin is bootstrapped, with a circular dependence among these three components. Nakamoto’s challenge was not just the design, but also convincing the initial community of users and miners to take a leap together into the unknown — back when a pizza cost 10,000 bitcoins and the network’s mining power was less than a trillionth of what it is today.

Public Keys as Identities

Bitcoin uses public keys as identities in the system. Transactions transfer value from and to public keys, which are called addresses. This notion of decentralized identity management dates back to David Chaum, the father of digital cash. In his 1981 paper, he states: “A digital ‘pseudonym’ is a public key used to verify signatures made by the anonymous holder of the corresponding private key”. The public-keys-as-identities idea is also seen in b-money and bit gold. Thus Bitcoin proved to be the most successful instantiation of Chaum’s idea.

Blockchains

Nakamoto makes no mention of the term blockchain. In fact, the term blockchain does not have a standard technical definition but is a loose umbrella term used by different parties to refer to systems with varying levels of resemblance to bitcoin and its ledger. Narayanan injects a dose of skepticism around blockchains for the following reasons:

-

Many proposed blockchain applications, especially in banking, don’t use Nakamoto consensus. Instead, they use the ledger data structure and Byzantine agreement which date back to the ’90s. This negates the claim that blockchains are a new and revolutionary technology. Instead, the buzz around blockchains has helped banks launch collective action to deploy shared-ledger technology, like the “stone soup” parable.

-

Blockchains are frequently presented as more secure than traditional registries which is a misleading claim. The systemic risk of blockchains may be lower than that of many centralized institutions, but the endpoint-security risk of blockchains is much worse. For example, in a blockchain-based stock registry, if a user loses control of her private keys, she loses her assets.

Conclusions and Lessons

The history described in Naryanan’s survey provides practitioners and academics rich and complementary lessons:

-

Practitioners should be skeptical about revolutionary technology claims. Most of the ideas in bitcoin that have generated excitement in the enterprise, such as distributed ledgers and Byzantine agreement, actually date back 20 years or more. Recognize that no breakthroughs may be required for your problem.

-

Academia seems to have the opposite problem of resisting to radical, extrinsic ideas. The bitcoin white paper was more novel than most academic research. We’ve seen repeatedly that ideas in the research literature can be gradually forgotten or unappreciated, particularly if they are ahead of their time.

-

Both practitioners and academics would do well to revisit old ideas to glean insights for present systems. Bitcoin was unusual and successful not because it was on the cutting edge of research on any of its components, but because it combined old ideas from many previously unrelated fields. This is not easy to do, as it requires bridging disparate terminology and assumptions.

-

It should be possible for practitioners to identify overhyped technology. Some hype indicators include, difficulty identifying the technical innovation; difficulty of finding meaning of supposedly technical terms, because of companies eager to attach their own products to the bandwagon; difficulty identifying the problem that is being solved; and finally, technology claims solving social problems or creating economic & political upheaval.

-

In contrast, it is difficult for academia to sell its inventions. For example, it’s unfortunate that the original proof-of-work researchers do not get credit for bitcoin, possibly because the work wasn’t well known outside academic circles. Engaging with the real world is a source of fresh ideas that not only helps get credit but also reduces reinvention.