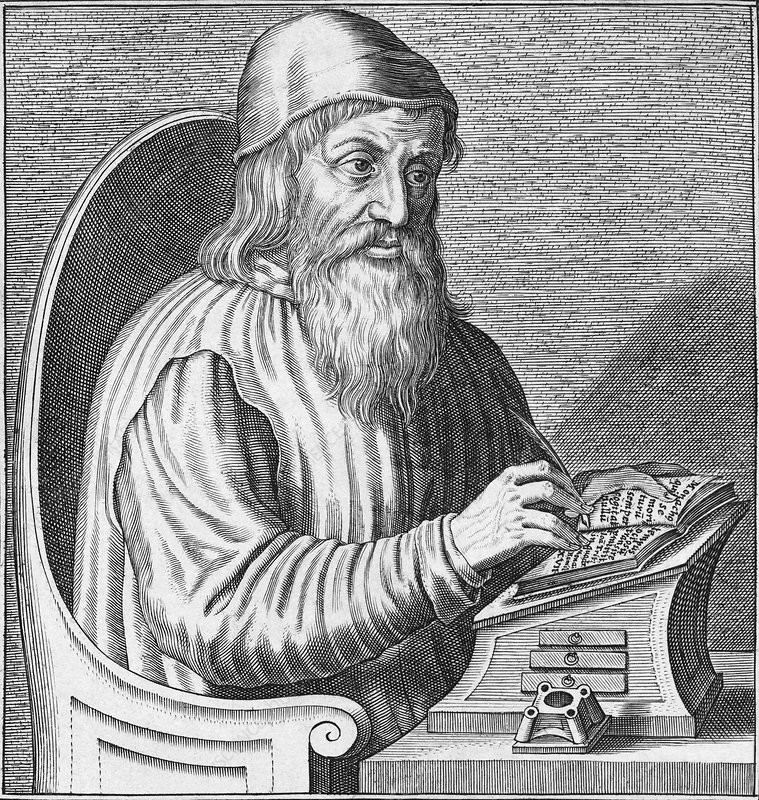

Johannes Trithemius, Archmage of Secrets

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

Johannes Trithemius, Archmage of Secrets

By David Morris

Posted November 6, 2019

In approximately 1499, in early Renaissance Frankfurt, a wunderkind bishop and magician named Johannes Trithemius completed work on a trilogy of books known as the Steganographia.

In approximately 1499, in early Renaissance Frankfurt, a wunderkind bishop and magician named Johannes Trithemius completed work on a trilogy of books known as the Steganographia.

The first two volumes were remarkable enough: they appeared at first to be concerned with magic, particularly techniques for using spirits to communicate over long distances. These books were not commercially published until 1606, but quickly after they became widely available, it was discovered that they were in fact written in code. The mystical ‘cover’ content was simply a ruse: the books were guides to the practice of ‘secret writing’ — or, in Latin, ‘crypto-graphia.’

They were among the first books ever published on the subject of code, and proved wildly popular — both in underground circulation during Trithemius’ lifetime, and in their later, wider release. Trithemius’ work on code likely had real-world impact, with use of the work specifically mentioned in histories involving secret government communication in the 17th century 1.

But the third book of the Steganographia was something different: even after being decoded, it appeared to be about matters of magic. It contains an inscrutable array of numerical tables and charts correlated to the names of angels (Geradiel, Uriel, etc.), purportedly all part of the method of calling on the power of these beings. Reputedly, Trithemius also destroyed portions of the work containing instructions for prophecy — though this was likely a bit of myth-making.

Incredibly, it wasn’t until nearly half a millenia after Trithemius penned this third volume that its true meaning was discovered. Two researchers discovered the truth, independently and nearly simultaneously — first a professor of German in 1996, and then an AT&T mathematician in 1998. What looked like coded descriptions of magical rituals were in fact instructions for secret communication2 — a code within a code.

Where Trithemius discussed using the power of spirits to communicate without words, he seems to have been winkingly referring to the power of numerical code to carry meaning. This is striking given that Trithemius’ work, taken at face value as a magical text, went on to be mined for centuries by would-be magicians hungry for methods to summon demons. It may also explain why Trithemius was not more aggressively condemned by the Church for his work during his lifetime — we can imagine him carefully explaining to ecclesiastical authorities that the Steganographia was not exactly as it seemed.

Secret writing as a practice, codified in a way theoretically accessible to a wide swathe of learned society, was itself a radical innovation in Trithemius’ time, and likely viewed with extreme concern by established authorities. And in fact, coded language became, in the latter half of the second millennium, a crucial element of statecraft and spycraft, intrigues and revolutions. The same force continues into the present day in the form of encrypted internet communication, making Johannes Trithemius, in quite a direct sense, the first cypherpunk.

But I’m concerned with a stranger connection within Trithemius’ project: What are we to make of his subversive act of obfuscation between code and magic? The Steganographia mined an existing conjunction between coded language and magic incantations: both a form of mystification, of obscuring. The word ‘occult,’ as Eugene Thacker and Mark Fisher have emphasized, takes its root from the Latin for secret or concealment. Magic deals in the occulted world — the planes of being beyond what humans can experience. Coded language created a new space for shared secrets, allowing a kind of ‘occulting’ of the social world3.

Magic is always a sort of symbolic obfuscation. Magical symbols are imbued with resonance and power through the process of what we would call memetics. By spreading through the minds of beings primed to believe in them, vague magical symbols can gain an eerie physicality: just as Trithemius metaphorized coded language as magical spirit-talking, the power of shared symbols can be described in supernatural terms as telepathy, curse, or mind control.

The fact that magical symbols are vague and indirect is precisely what can give them real-world power, when wielded by certain hands. For the well-intentioned magician, perhaps a poet or shaman, the vagueness of magical symbol can become a pathway to insights that are not easily articulated in precise, rational terms. But in the wrong hands, for instance those of a political demagogue, magical language, chants and symbols can organize impulses too dark for the human spirit to accept when stated outright.

In this very real way, the practice of magic harnesses the misty realm of things like consciousness, reflection, and intention, connecting them to indeterminate symbols that can nonetheless push through into the hard-edged world of action and impact. Magic becomes an alternate frame for viewing a wide spectrum of social incantations — the Pledge of Allegiance is a ritual of binding, each paycheck an indulgence, the iPhone a saintly fetish, whispering hallucinations. Magic is threaded throughout our obsessive, repetitive world.

Coded language is in a sense the inverse. Its essence is actionable, meaningful data or expression. The series of mathematical transformations enacted on that data — the ritual, if you will — replaces legible content with seemingly random signals. It renders the message unintelligible except as a message. Like McLuhan’s light bulb, code is itself nothing, yet refigures a base dimension of (social) reality. Where once we were in darkness, Edison brought light. And conversely, where once we had only words with meaning, Trithemius brought the world secret messages, pings, blips — visible but unknowable information.

Trithemius had to be a visionary to grasp the worth of coded communication. But we take it for granted, encountering coded messages daily without truly seeing them: scanning systems, identification cards, and, of course, computers. There are reasons both of real secrecy and mere efficiency behind the use of codes for communication between organizations or agencies or governments. But for whatever reason, the sort of code pioneered by Trithemius has become a major tool for ordering, regulating, and managing our societies and our world.

Our existence within a coded reality — our daily encounter with the UPC code on the goddamn cereal box — can be regarded as the postmodern corollary to the mysteries of nature confronted by our long-ago ancestors. Once it was the outside world that constantly hid its deeper principles from us. Now our fellow humans do the same.

And just as the mysteries of nature gave birth to attempted explanations in the form of myth, folklore, and religion, the mystery of code primes our being to quest into darker levels of social (un)meaning. If everything is code, where beyond or below the apparent everyday are the lines of communication and levers of power that guide both the agreements of the powerful, and the resistance of the weak? Could these messages be all around us, yet evade our notice?

Among other things, then, code becomes a way for humans to revive a sense of the mystical. Its practice and, perhaps more importantly, its cultural resonance, have allowed our highly advanced and regimented society to retain something of its wildness. We are animals, and ultimately, we demand freedom and possibility. We demand, even, risk and chaos.

. . . This is the first part of one chapter of my new book, Bitcoin is Magic. I’ll be publishing the rest of the chapter soon . . . or you can just grab the book, in paperback or for Kindle, today.

-David Morris

1 Robert Hooke (1705). The Posthumous Works of Robert Hooke. Richard Waller, London

2 This is according to AT&T’s Dr. Jim Reeds, one of two researchers independently broke Trithemius’ code.

3 If Trithemius was just posing as a ‘magician’ while in fact remaining faithful to his Catholicism, he is also a useful figure for definition of ‘magic’ in contemporary politics and ideology. We have mentioned the formulation, drawn from Aleister Crowley and carried on by Alan Moore, that magic is an attempt at direct, individual intervention in the world. For Moore, religion is in particularly stark contrast to this, as a form of submission to authoritarianism — but there is a converse formulation, by which religion is a vehicle not for submission, but for faith. Faith is a spiritual submission to being itself as a mystery beyond any mere human grasping, and implies an ultimate rejection of ANY human authority in the face of the numinous, mystical all-power of God.

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |