Privacy and Cryptocurrency, Part I: How Private is Bitcoin?

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

Privacy and Cryptocurrency, Part I: How Private is Bitcoin?

Eric Wall

March 7, 2019

This is part 1 of a series

- Privacy and Cryptocurrency, Part I: How Private is Bitcoin?

- Future post here

Foreword

The Human Rights Foundation cares deeply about protecting our civil liberties and privacy in our increasingly digital age, especially in places where people live under authoritarian governments. Without a free press, without local watchdog organizations, and without effective ways to hold governments accountable, the 4 billion people who live under authoritarianism need our help, and technology is one way we can reach out. As we’ve seen with the evolution of encrypted messaging, virtual private networks, and free knowledge initiatives like the Tor Project, Wikipedia, and Signal, technology can be a liberation tool, if built with the right values in mind. But as we’ve seen with centralized platforms ranging from Facebook to WeChat, technology will also be a tool of surveillance and even social engineering.

Unless we take a stand now, and help make platforms and protocols with user privacy and decentralization in mind, mass surveillance and social credit may be the inevitable future. To help elevate this conversation, the Zcash Foundation has provided generous support for HRF to bring Eric Wall on as a Technology Privacy Fellow. Eric will be working with HRF for the next six months, writing five essays on privacy technology, with a special focus on cryptocurrency and how we can preserve privacy in the financial world. We look forward to sharing Eric’s work with you, and seeing it inspire fresh conversations with policymakers, philanthropists, investors, students, and the builders of our current and future technology infrastructure.

— Alex Gladstein Chief Strategy Officer Human Rights Foundation —-

Key points:

- If you’re an activist or a journalist, you may wonder how safe it is to use bitcoin to escape the prying eyes of a government or corporation

- Bitcoin is only semi-private; the protocol doesn’t know your real name but transactions can still be linked to you in a myriad of ways

- Blockchain analytics firms specialize in deanonymizing bitcoin activity and sell this data to corporations and law enforcement agencies

- A grasp of how the system works and use of tools such as Tor, coin control, CoinJoin transactions and avoiding address reuse can make a crucial difference in protecting your identity and transactions from being unmasked

- This article aims to give the reader a primer on Bitcoin privacy — later articles in the series will look at different wallets, compare different cryptocurrencies and survey exchange platforms in regions with restricted economic and political freedom

Why cryptocurrencies?

It’s clear from the onset when observing cryptocurrencies at a protocol level that they are inherently more privacy-oriented than traditional digital payment systems. At the base layer of these protocols, there is typically no mapping between users’ cryptographic key pairs and their real-world identities, yet they allow us to store and transfer wealth across the globe with an unprecedented degree of freedom.

The intention of the Human Rights Foundation is to examine these technologies and elucidate on their potential of bringing economic and political freedom to the individual. While there are many angles in the context of money that are within the scope of such an endeavor, we’ve chosen to focus on the topic of privacy foremost. In that pursuit it’s also clear that the degree to which cryptocurrencies enable privacy is not by any means trivial or binary — it varies greatly depending on the user’s particular choice of core and ancillary technologies and usage patterns, as well as the capabilities and sophistication of the attacker.

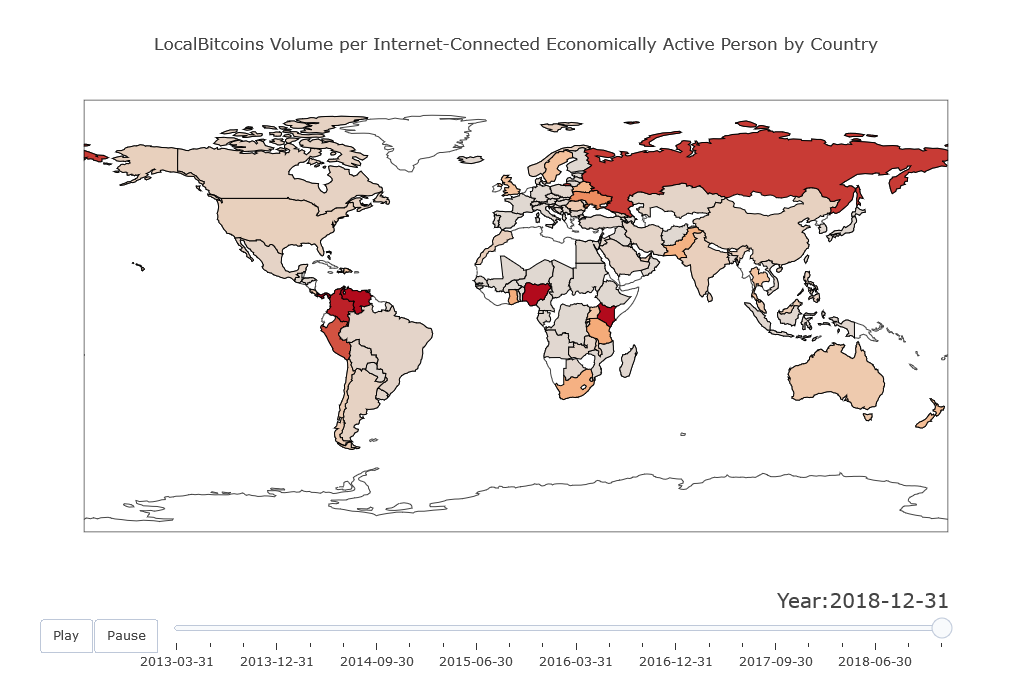

Regardless of that, we can observe that the adoption rate of cryptocurrencies — in particular, bitcoin — is increasing in countries where the economic freedom of the population is limited. While the liberating and democratic aspects of cryptocurrencies are apparent, especially the extent to which they enable censorship-resistant transaction networks and monetary policies impervious to various forms of government sabotage, none of these benefits are particularly helpful as long as authoritarian regimes can deanonymize and prosecute the users of these currencies at will.

Many thanks to Matt Ahlborg for lending us this visualization from his great piece “Nuanced Analysis of LocalBitcoins Data Suggests Bitcoin is Working as Satoshi Intended “ which explains the exact methods used to generate it.

Many thanks to Matt Ahlborg for lending us this visualization from his great piece “Nuanced Analysis of LocalBitcoins Data Suggests Bitcoin is Working as Satoshi Intended “ which explains the exact methods used to generate it.

The ambition of this initiative is to cut through the complexity of the cryptocurrency privacy subject by sourcing subject matter expertise from the industry. When we approach this subject, we recognize that we enter into a complex field, and as in any complex field, experts disagree. We will strive to strip this initiative from personal biases and condense opinions and research into simple practical guidelines.

The product of this research will be an article series of which this is the first piece.

A primer on Bitcoin privacy

Bitcoin is neither completely anonymous nor completely transparent. The Bitcoin privacy conundrum exists in a grey area where the unmasking of a user’s financial activity ultimately depends on the capabilities of the adversary and the sophistication of the user and their choice of tools. There is no perfect privacy solution for any activity on the Internet, and in many cases, privacy-conscious choices come with tradeoffs to both cost and ease-of-use where no one-size-fits-all solution exists. Moreover, privacy is never a static thing but evolves continuously and in response to the battle between those who build tools to protect privacy and those who build tools to destroy it.

The Bitcoin protocol itself evolves over time, which can lead to dramatic changes in its privacy properties. Changes to the core protocol are seldom simple choices between privacy and transparency alone, but more often come packed with changes to the security, scalability, and backward-compatibility of the software as well. Historically, the trend and ethos within the Bitcoin community has always favored privacy over transparency, but more conservatively so compared to other cryptocurrencies where privacy is the primary focus.

As a result, activists or journalists who are considering using bitcoin to escape the prying eyes of an authoritarian government or a corporation need to understand what type of traces they leave when they’re using it and whether the privacy nature of bitcoin is sufficient for their needs. However, achieving this understanding requires some amount of effort.

Tracing transactions

When you transact on the Bitcoin network you leave two types of traces. These can be categorized into “what’s on the blockchain” and “what’s not on the blockchain”. The information that is on the blockchain reveals no direct link between your identity and your transactions, but it does reveal information that can link your transactions to each other. What does link your identity to your transactions are the things in the second category: “what’s not on the blockchain”.

What’s not on the blockchain

When you transact on the Bitcoin network, you are sometimes sending or receiving money to/from some entity that knows who you are. That entity will then have outside-of-the-blockchain-knowledge that links your identity to a transaction.

When you combine this fact with the other fact that your transactions can be linked to each other, the result is that motivated entities can sometimes figure out how you’re using your bitcoins, how much you have and who you’ve been transacting with.

There are also countless ways you could be linked to a transaction even without having transacted with an entity that knows who you are, since Bitcoin transactions are typically sent in unencrypted packets over the Internet and the source IP address can be pinpointed through various means. Bitcoin transactions sent via full nodes such as Bitcoin Core require some triangulation or targeted traffic sniffing in order for the source IP address to be estimated, whereas other “light” wallets such as mobile wallets (Mycelium, Blockchain Wallet, Coinbase Wallet) will often broadcast transactions through company-run servers that can see your IP address directly and your full transaction history. The same is true for most hardware wallets (Ledger, Trezor) in their out-of-the-box setups.

Geolocation IP databases can often roughly approximate your physical location using your IP address. You can test it out yourself using this link, then enter the coordinates you get into an interface like Google Maps. More importantly, your IP address reveals your Internet Service Provider (ISP), which in turn knows the real-world identity of the owner of your IP address and often has a legal obligation to store this information for several months.

Even if you are using a public WiFi network to transmit your transactions, you could still accidentally associate your real identity with that IP address from the websites you visit and the background services your device connects to. Your Dropbox application will gladly connect to Dropbox’s company servers when you start your laptop which will associate that IP address with your Dropbox account in Dropbox’s server logs. The same thing will happen when you browse to a personal account on any website. Even if you don’t visit any personal web accounts, cookies stored on your laptop can reveal who you are to the website you browse to through your cookie’s association to your previous browsing history. Many websites allow third parties to track users like this for analytics purposes — Google alone is estimated to track users across 80% of the sites of the entire web.

Even if you clear your cookies, website operators can track you across their different sites as long as your browser fingerprint is unique and associate your IP address to your identity that way. And even if you have no services running and avoid browsing altogether, your device’s MAC address could get exposed to the network provider which could be linked to your identity using sophisticated methods. So, even if your IP address doesn’t lead back to you via an ISP record, you might still leave other traces that do when you’re using your personal devices.

The worst category for privacy is of course when using third-party services that implement know your customer (KYC) practices as your Bitcoin wallet, as these services will keep logs of all your transactions and your real-world identity.

You could also be linked to a Bitcoin address or transaction just by searching for it using web-based tools since there usually aren’t that many people other than you who are going to be looking up your transactions on the web for no good reason. Keep this in mind as we move to the next segment. Other data that isn’t on the blockchain but can easily be logged about your transaction is the approximate time it was broadcast to the network.

The current known best method to hide your source device and IP address when retrieving information about transactions or when transmitting transactions is to leverage Tor hidden services. Many wallets including Bitcoin Core will provide this as a configurable option while others have it built-in. The Tor browser can similarly be a useful tool for your web-based Bitcoin-related activity as it, in addition to hiding your IP address, clears cookies upon each exit, prevents third-party cookies and is immune to most browser fingerprinting techniques.

What’s on the blockchain

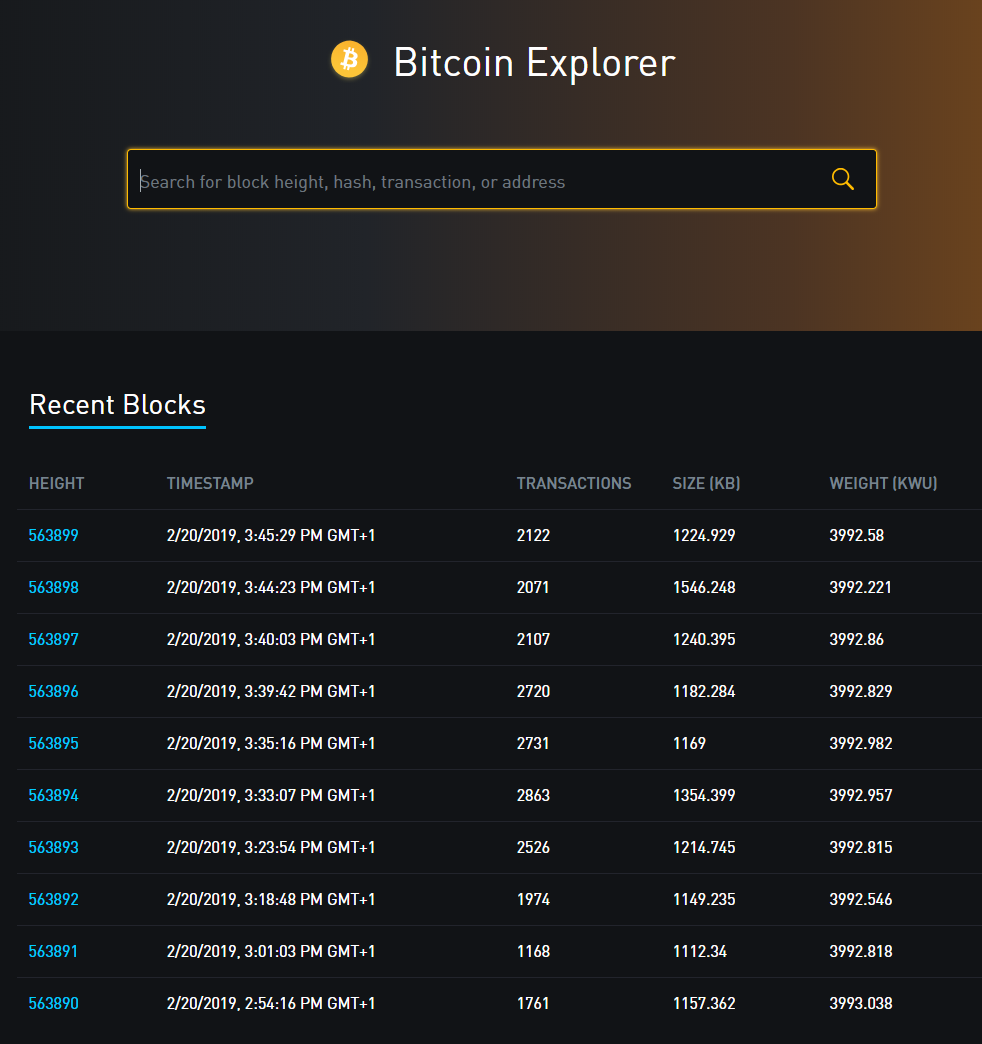

A simple way to begin understanding what type of information is revealed by the Bitcoin blockchain is to use a block explorer. For this exercise, we’ll use the open-source explorer blockstream.info.

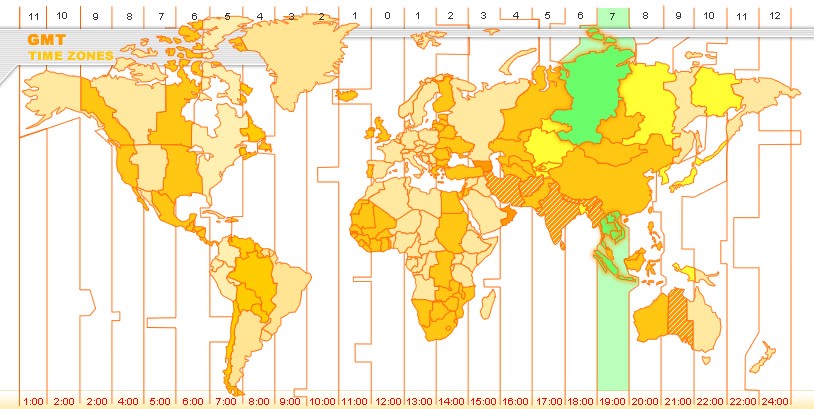

The most recent block at the time of writing (#563899) in the Bitcoin blockchain contains 2122 transactions. Let’s look at what a randomly chosen transaction reveals.

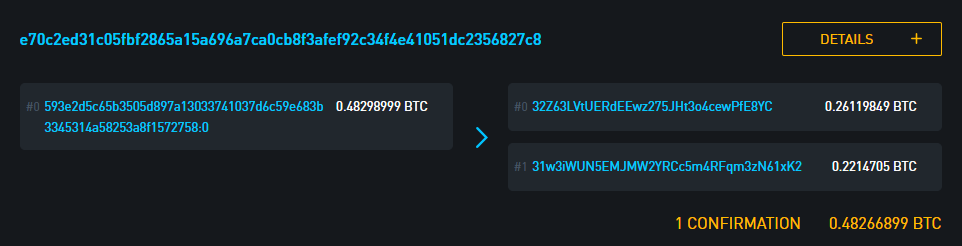

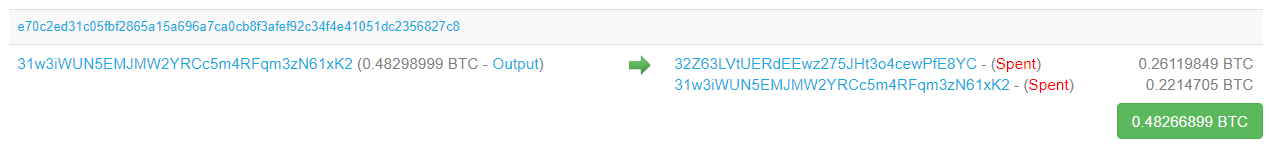

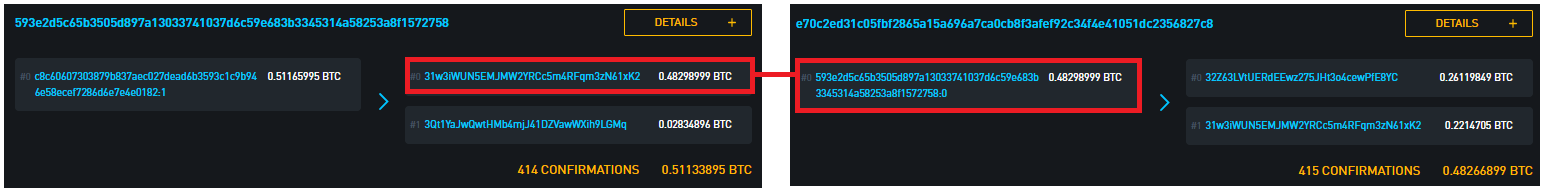

Transactions contain inputs and outputs and are identified by transaction IDs (seen at the top in the image above). If your Bitcoin wallet has sent a transaction, each transaction will be associated with one such identifier.

From a high-level view, what is revealed about this transaction is the following:

- The approximate time the transaction was mined (from the block header)

- The addresses bitcoins were sent to and the amounts sent (i.e. the “transaction outputs”)

- The source of the funds for the transaction (i.e. the inputs)

Let’s look at each of these items individually for the transaction shown above, e70c2ed31c05fbf2865a15a696a7ca0cb8f3afef92c34f4e41051dc2356827c8

Time

Transactions are not timestamped, but blocks are. Block timestamps are not necessarily precisely accurate, but assuming a majority of miners are reporting time honestly, all blocks are bound to be reasonably accurate within a few hours range. For the blocks mined by the honest miners, they’ll be precisely accurate. This doesn’t mean that the block timestamp is necessarily accurate within a few hours range to its transactions’ broadcast times however, since it can sometimes take a lot longer for a transaction to be included in a block. Some block explorers complement data this by displaying the time they first saw a transaction on the network to give a more accurate view of transactions’ broadcast times.

The approximate time when the transaction above was included in a block can be derived by looking at the block header (in our case it’s block #563899 with the timestamp 2019–02–20, 14:45 UTC).

The addresses bitcoins were sent to and the amounts sent

The receiving addresses in this transaction are:

1: 32Z63LVtUERdEEwz275JHt3o4cewPfE8YC 0.26119849 BTC

2: 31w3iWUN5EMJMW2YRCc5m4RFqm3zN61xK2 0.2214705 BTC

There is more to an address than what meets the eye. It’s easy to think of Bitcoin addresses as “hard-to-read email addresses but for bitcoins”, but an address isn’t always a simple pointer to a certain user’s cryptographic key-pair. What addresses are in reality, are cryptographic descriptors of the spending rules for the next time someone wants to move those bitcoins.

For example, if you send bitcoins to:

37k7toV1Nv4DfmQbmZ8KuZDQCYK9x5KpzP

the configuration of this address is such that you’re not sending bitcoins to an owner of a particular private key, but rather to a spending rule that releases the coins to anyone who can provide two different strings that have the same SHA-1 hash (this would mean that the SHA-1 hash function is broken, which it was in 2017— so don’t send anything to that address!). What’s good to note is that since many address formats used today are hashed when we send bitcoins to them, we t ypically can’t tell what those spending rules are until someone spends bitcoin from that address, as they need to reveal what was hashed in order to do so.

In our example transaction, the blockchain reveals that bitcoins have been spent from both addresses, so the spending rules for those addresses are known.

32Z63LVtUERdEEwz275JHt3o4cewPfE8YC

was revealed to be a 2-of-2 multisignature address when it was spent from in the transaction

f491dfe9867c36e85950116a90a6128060d6070866ad0f3598d70d146750162f

We’ll look at exactly how that information is revealed in the next section.

Similarly, it was revealed of

[31w3iWUN5EMJMW2YRCc5m4RFqm3zN61xK2](https://blockstream.info/address/31w3iWUN5EMJMW2YRCc5m4RFqm3zN61xK2)

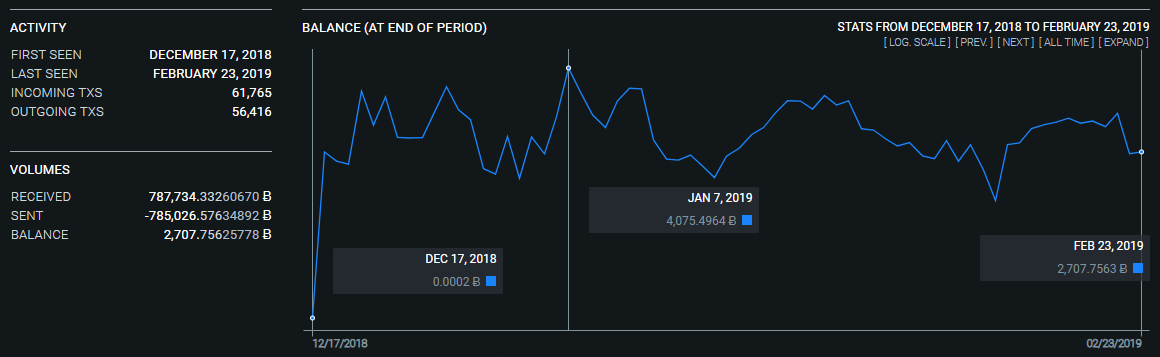

that it is a frequently used 2-of-3 multisignature address and at the time of writing holds roughly 2,700 bitcoin (US$10.6m). More advanced blockchain tools such as oxt.me will even plot the wallet balance over time and display with approximate accuracy which hours of the day it has seen the most activity.

Historical balance and activity relating to the address 31w3iWUN5EMJMW2YRCc5m4RFqm3zN61xK2 (oxt.me).

Historical balance and activity relating to the address 31w3iWUN5EMJMW2YRCc5m4RFqm3zN61xK2 (oxt.me).

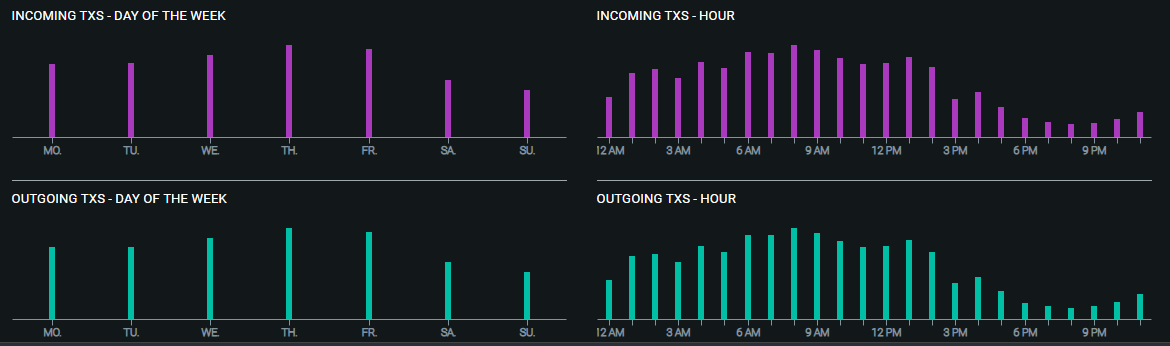

Seeing as 18:00-22:00 UTC are the hours with the least activity for this address, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to assume that these hours represent the night-times 01:00-05:00 or 02:00-06:00 in the region where the address is controlled. Given the hours of activity, the volumes and the multisignature setup of this address, one could guess that this address belongs to a cryptocurrency exchange in the GMT+7/8 time zones.

It’s considered good privacy hygiene to never reuse a Bitcoin address because it helps to break transaction linkage. That’s also a good idea for all users of P2SH addresses (all addresses starting with a “3” and 62-character addresses starting with “bc”) because by the time you reveal what the spending rules are for that address, you’ve already sent the bitcoins to a new, hashed address for which the spending rules are yet unknown.

Wallets known as HD wallets can generate many addresses but only require a single back-up seed in order to access the funds. These wallets will also automatically generate a fresh address for you every time you’ve received a transaction.

Now let’s look at the transaction again to see what else we can reveal about the sent coins.

Bitcoin transactions are regularly directed towards two addresses where one of the transaction outputs is the actual payment and the other is what is known as a “change output” going back to the sender. It’s similar to when you pay for a $3 item with a $5 bill, it creates two payments; one of $3 to the merchant and one with the change of $2 going back to the one paying.

Identifying a transaction output as a change output requires the use of heuristics .Examples of heuristics that can be used to discern a change output from the other payment are; the usage of round numbers (in the bitcoin amount or in the fiat currency value of the amount at the time of the transaction), the order of the outputs in the transaction body and so on. In our chosen transaction, it’s easy to detect the change output because it’s going back to the same address that was used to receive the bitcoins that were spent, as we’ll see below.

In principle, Bitcoin wallets behave somewhat differently from each other and leave different traces on the blockchain — similar to how browsers reveal pieces of information about themselves when they browse the web. Because of this, it is sometimes possible to identify certain transactions as originating from a certain kind of Bitcoin wallet application.

If your adversary knows which wallet application you’re using then that knowledge can contribute to mapping your identity to one of your transactions, which would weaken your privacy. Every little piece of information helps an adversary paint a picture of who you are and what you are doing.

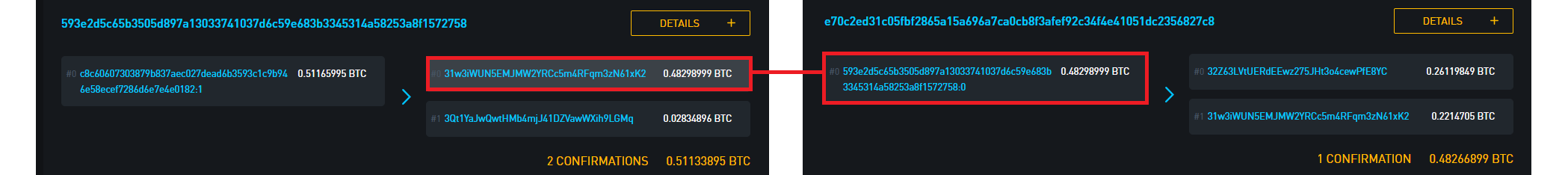

The source of funds for the transaction

In Bitcoin transactions, the “source of funds” is always other “unspent” transactions, or to be precise, unspent transaction outputs (known as UTXOs). It’s good to keep in mind that what is seen in a block explorer is a combination of decoded raw blockchain data and derived data. One block explorer might choose to display the transaction like this:

From blockchain.com.

From blockchain.com.

Here the “source of funds” is displayed as an address. Blockstream’s explorer chooses to display it like this, where the source of funds is displayed as a transaction:

The reason why Blockstream’s explorer doesn’t show an address as the source of funds is that addresses aren’t technically a part of the inputs to a transaction and it isn’t always possible to infer the notion of an originating address (example). Moreover, since address reuse is discouraged, it’s good to break inherited mental models from traditional payment systems and not further cement the idea that money could or should be sent back to the recipient at the same address by showing addresses as senders.

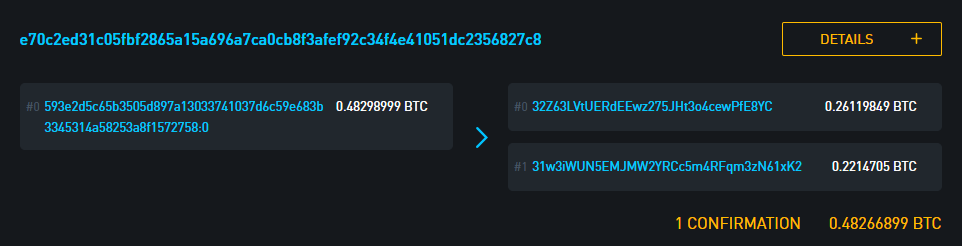

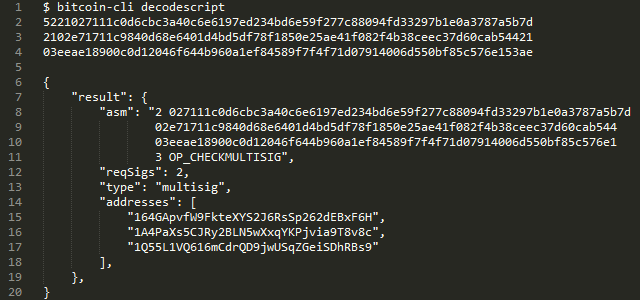

Let’s get more technical for a moment and look at the decoded raw data of the transaction, which you can fetch from your own local copy of the Bitcoin blockchain if you run a full node (or by using a trusted web-based interface). Here’s what it looks like:

e70c2ed31c05fbf2865a15a696a7ca0cb8f3afef92c34f4e41051dc2356827c8 decoded (manually trimmed).

e70c2ed31c05fbf2865a15a696a7ca0cb8f3afef92c34f4e41051dc2356827c8 decoded (manually trimmed).

The source of funds is described by the vin-array. It doesn’t refer to an address specifically. Instead, it refers to the output of a previous transaction;

593e2d5c65b3505d897a13033741037d6c59e683b3345314a58253a8f1572758

, where vout: 0 refers to that transaction’s first output (vout: 1 would mean its second output, and so on). This unspent transaction output (UTXO) is the source of funds.

To clarify what this means, the source of funds for a transaction is not an address, nor is it a transaction. The source of funds is a specific output of a specific previous transaction. Knowing this will help you protect your privacy when using bitcoin, as we’ll see in later sections.

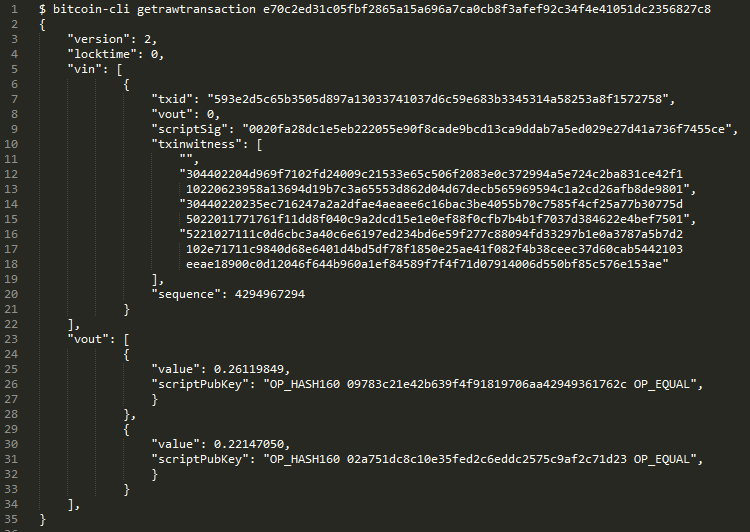

The source of funds for e70c2ed31c05fbf2865a15a696a7ca0cb8f3afef92c34f4e41051dc2356827c8.

The source of funds for e70c2ed31c05fbf2865a15a696a7ca0cb8f3afef92c34f4e41051dc2356827c8.

We can further decode parts of this transaction from the decoded raw data such as what’s in txinwitness to find out more about the source of funds. The last hexadecimal string in txinwitness reveals the 2-of-3 multisiginature script, which allowed us to deduce that it’s likely to be an exchange wallet.

The two other hexadecimal strings we saw in the txinwitness are just the signatures fulfilling this 2-of-3 multisignature condition.

Now that we’ve identified the source of funds, we can see in this example that it’s a 0.48298999 bitcoin output (~US$1850), even though the sent payment was just one of ~US$1000. This has an undesirable consequence: imagine a situation in which a friend pays you $10 but the transaction reveals that he’s the owner of a million dollars and has immediate access to send the full amount— obviously not very good for privacy. If you are worried about disclosing information about your bitcoin wealth when you are sending a payment to someone, you need to be aware of which inputs are used in your transactions (more on this below).

Combining the knowledge

Because transactions always need to provide the source of funds, transactions become linked together, producing what’s known as a transaction graph. If you pay a friend in bitcoin, not only will your friend see the inputs you used in the transaction, but you will also be able to see when your friend spends those coins and to which addresses the coins are sent.

Some addresses are known in the Bitcoin space, such as the Bitfinex cold wallet or the seized Silk Road coins. An address can become known because an entity — for example, a business or a charity — advertently exposes their deposit or donation addresses on their website, or inadvertently because a forum post or a law enforcement record publicly reveals the connection. Blockchain analytics firms will scrape the web regularly to find such information.

Other addresses become exposed via association through a technique called clustering.

Clustering

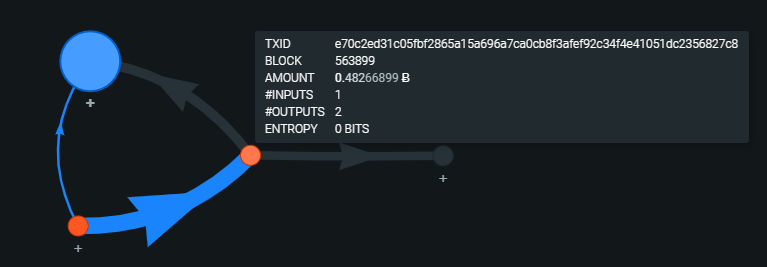

Let’s go back to our example transaction from the previous examples, e70c2ed31c05fbf2865a15a696a7ca0cb8f3afef92c34f4e41051dc2356827c8. Here, we can immediately see that both the source of funds of our transaction and our transaction (red dots) have been used to jointly fund a third transaction (big blue dot).

Transaction graph for e70c2ed31c05fbf2865a15a696a7ca0cb8f3afef92c34f4e41051dc2356827c8 (oxt.me).

Transaction graph for e70c2ed31c05fbf2865a15a696a7ca0cb8f3afef92c34f4e41051dc2356827c8 (oxt.me).

Particularly, it’s the second output of the funding transaction and the first output of our transaction that are involved in funding this transaction. They were previously sent to the addresses:

3Qt1YaJwQwtHMb4mjJ41DZVawWXih9LGMq

32Z63LVtUERdEEwz275JHt3o4cewPfE8YC

On the surface, these appear to be two separate addresses with just one innocuous-looking incoming and outgoing transaction each. But because their private keys have both been used to sign the big blue dot transaction, these addresses now all belong to the same cluster (along with 407 other addresses involved in the inputs to the transaction), which we can make assumptions about having the same owner. This heuristic has gone under a couple of different names in the past, the most recent one being the common-input-ownership-heuristic.

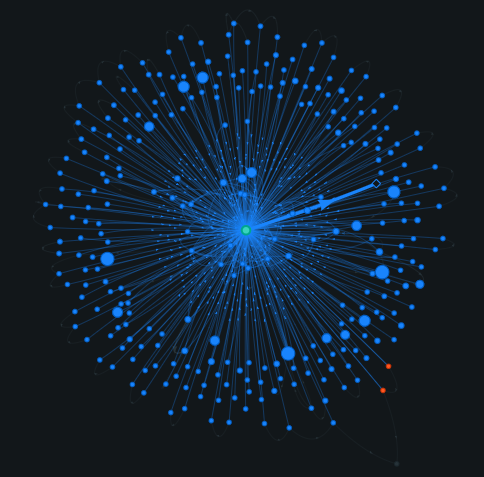

Transaction graph for “the big blue dot” transaction f491dfe9867c36e85950116a90a6128060d6070866ad0f3598d70d146750162f (oxt.me).

Transaction graph for “the big blue dot” transaction f491dfe9867c36e85950116a90a6128060d6070866ad0f3598d70d146750162f (oxt.me).

Blockchain analytics firms will use such heuristics to create giant clusters. The blockchain explorer WalletExplorer has pinned the two addresses to belong to a cluster of 162787 addresses in total. Analytics firms label such clusters with all identities (IP addresses, user accounts, organizations, real names) they’re able to pin to the cluster in order to map out the Bitcoin transaction ecosystem. They then sell access to these data sets to law enforcement agencies and other companies.

Many blockchain analytics firms receive information about transactions directly from their own customers, such as cryptocurrency exchanges. However, two of the largest analytics firms, Chainalysis and Elliptic, have stated that they do not trace back transactions to specific individuals in the data they receive, but only to the exchanges or other business entities (1, 2).

It only takes the deanonymization of one address in a cluster to deanonymize an entire cluster.

Breaking the heuristics

We’ve seen now that there are a multitude of ways your identity can be linked to a certain Bitcoin address or transaction and yet another multitude of ways your Bitcoin transactions can be linked to each other. When put together, these information leaks in combination can unmask our entire financial privacy.

Some Bitcoin users intentionally try to make this kind of analysis difficult by using tools and techniques to break the heuristics analytics companies employ. Some techniques decrease the effectiveness of the heuristics through distortive methods while others attempt to avoid the heuristics altogether. Bitcoin wallets can assist users by automating some of these techniques or make them available through a user interface.

Here’s a non-exhaustive list of some examples:

- Randomizing the order of outputs when creating transactions to decrease change output detection accuracy (example).

- Avoiding address reuse via HD wallets.

- A PayNymis a publicly sharable ID which allows you to receive payments at different unassociated addresses you control that only become known to you and the sender. The PayNym allows a new address to be derived for each payment without you having to manually present a new address each time, which is great if you want to conveniently receive, say, donations online using bitcoin.

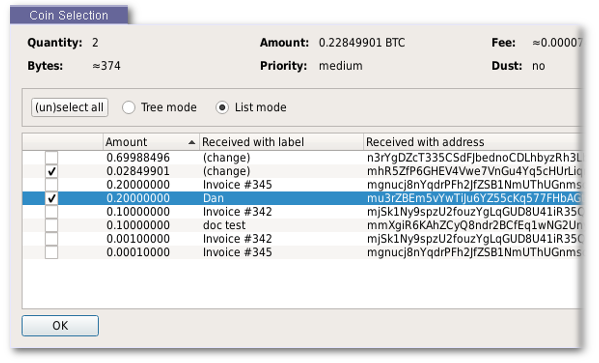

- Coin selection/coin control — wallets can be designed to prioritize clustering fewer addresses together when possible by selecting inputs for transactions more carefully (example), or allow users to select inputs for transactions manually to avoid revealing ownership of certain coins (example).

Coin control in Bitcoin Core — user can manually choose the source of funds for a transaction.

Coin control in Bitcoin Core — user can manually choose the source of funds for a transaction.

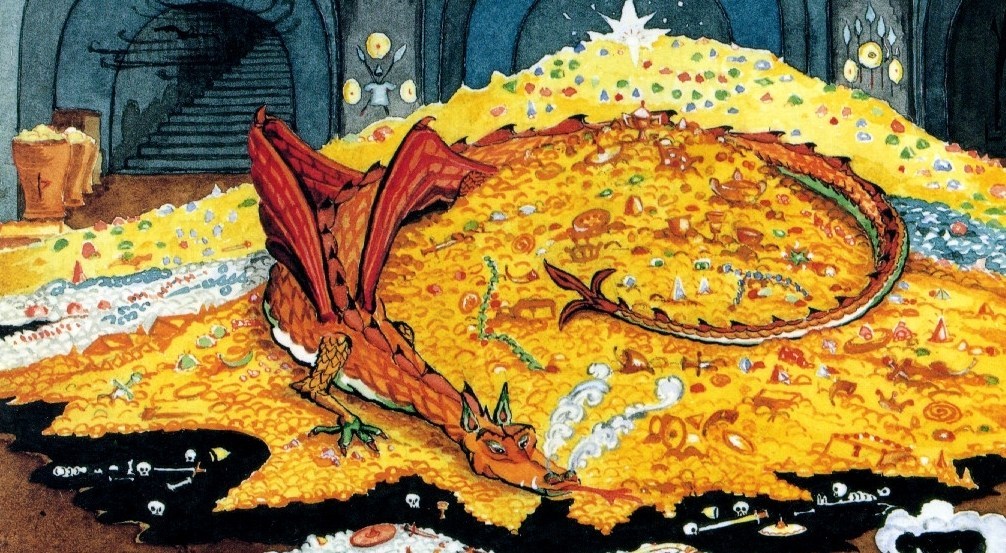

A more advanced example of a privacy-enhancement technique is CoinJointransactions. CoinJoins are a scheme which adds many inputs from many different users into a joint transaction before the transaction is broadcast.

In our example, we saw how the input of a transaction always references a specific output of a previous transaction, rather than the whole transaction:

The source of funds for e70c2ed31c05fbf2865a15a696a7ca0cb8f3afef92c34f4e41051dc2356827c8.

The source of funds for e70c2ed31c05fbf2865a15a696a7ca0cb8f3afef92c34f4e41051dc2356827c8.

But the inputs and the outputs within each individual transaction don’t reference each other in any way; transactions are valid as long as there’s enough bitcoin in the inputs to cover all the outputs.

A CoinJoin transaction (72046c65fa25724f11c91f35799f69b66072bc07b2b4e3fc363852c2506b2b90) created by the Wasabi Wallet.

A CoinJoin transaction (72046c65fa25724f11c91f35799f69b66072bc07b2b4e3fc363852c2506b2b90) created by the Wasabi Wallet.

Here, the outputs are chopped up into many equal-amount chunks, so you can’t be sure which input funds which payment. The result is that a payment can have a plethora of possible “source of funds” indiscernible from one another, as well as a plethora of possible destinations. This technically doesn’t hide the source of funds or the destination, but it mixes it so that it becomes difficult to prove what actually funded a particular payment and who’s bitcoins went where.

What’s also interesting about these kinds of transactions is that they complicate the idea of the common-input-ownership-heuristic. These inputs would all get flagged as belonging to the same owner, which in this transaction they aren’t. The images below show false clusters of independent payments as a result of CoinJoin transactions.

CoinJoin transactions created by the Wasabi Wallet. Transaction IDs from left to right: 72046c65fa25724f11c91f35799f69b66072bc07b2b4e3fc363852c2506b2b90, d7a428a8e3d69f236519cb999dbcb47b3b283548875371da567259be806e35ea, 20cf4fa2f685167f46682dd30c7720a06618656939fadbd1f20e3d471d08dfbb (oxt.me).

CoinJoin transactions created by the Wasabi Wallet. Transaction IDs from left to right: 72046c65fa25724f11c91f35799f69b66072bc07b2b4e3fc363852c2506b2b90, d7a428a8e3d69f236519cb999dbcb47b3b283548875371da567259be806e35ea, 20cf4fa2f685167f46682dd30c7720a06618656939fadbd1f20e3d471d08dfbb (oxt.me).

But because these transactions all have the odd look of equal-amount outputs, they’re rather easy to spot and can be eliminated from the clustering analytics tools. Equal-amount CoinJoin transactions are best understood as mixers to be used when one wishes to obfuscate the source of funds for a payment and the destination to which a payment is sent.

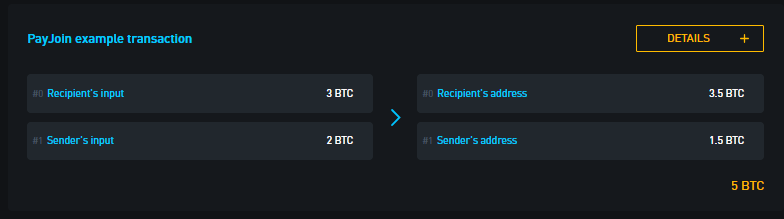

However, the same principle is used to create transactions that are indistinguishable from normal transactions in a recent invention called a PayJoin or Pay-to-EndPoint (P2EP). This emerging transaction type mixes inputs from the payer and the recipient and pays the recipient by shifting over the payment amount from the sender’s output and to the recipient’s output during a real payment for something.

A PayJoin transaction template where the sender pays 0.5 bitcoin to the recipient, mixing inputs with each other in the process.

A PayJoin transaction template where the sender pays 0.5 bitcoin to the recipient, mixing inputs with each other in the process.

This transaction doesn’t do a lot of mixing — but it does trigger the common-input-ownership heuristic erroneously. More importantly, it triggers the heuristic without leaving any clues for the analytics firms to not cluster the inputs together, which they would need to in order to avoid giving false positives. If the usage of PayJoins becomes widespread, the portion of false common-input-ownership positives could become so great that the heuristic itself becomes unreliable, which would be a massive setback for the blockchain analytics tools.

The Lightning Network

The Lightning Network is a beta technology that is being developed on top of the Bitcoin protocol to facilitate low-cost, instant payments. The Lightning Network is accessible to users of Lightning wallets. Lightning transactions differ from base-layer transactions in many ways which make them advantageous from a privacy perspective:

- Lightning transactions are not stored on a public ledger.

- Lightning transactions use onion routing which doesn’t disclose who the final recipient is to the rest of the network.

- Lightning transactions don’t mix inputs and can’t be clustered together.

The Lightning Network is a system of channels which require liquidity; the current set of merchants and users that accept Lightning payments today are a small subset of the total set of Bitcoin users in the system, and not all payments (especially larger ones) can propagate through the channel system, although that is expected to improve over time. This also means that while Lightning can provide improved privacy for the transactions in its channel system, those channels still need to be funded by regular Bitcoin transactions, which are subject to the privacy concerns in this post.

Another problem is that unlike base-layer Bitcoin payment recipients, recipients of Lightning payments are required to have a Lightning node running. Your node communicates with other Lightning nodes using TCP/IP. Whenever your node interacts with the network (sending, receiving or routing other payments) someone will learn about the existence of your node, its public key and its IP address. From your public key, it’s trivial to find out which channels are open between you and other nodes, and how many bitcoins you each have committed to those channels upon opening them. For private channels, the IP address is only revealed to the ones you have an open channel with, but for public channels, it’s revealed to the entire network and it’s even possible for someone to probe the channels’ current balances to figure out if you’re a target worth attacking.

When you run a Lightning node, you should assume that your channel balances are known and that they can be linked to your IP address. For this reason, running your Lightning node over Tor is a good option to protect your privacy.

The Lightning Network is currently under quite rapid development and many of its properties might be subject to change in the near future.

Protocol changes

There are several privacy-enhancing technologies that are in development for the base-layer Bitcoin protocol. Here are a few examples:

- Schnorr signatures — a signature scheme which, among other improvements, makes multisignature addresses indistinguishable from single-signature addresses

- Scriptless scripts — a method by which to use scripts without disclosing the actual spending rules

- Taproot — a technique with the potential of making transactions of all types of spending rules indistinguishable from each other

Conclusion

This article aims to give a primer to how privacy works in Bitcoin. The pseudonymous but transparent nature of the Bitcoin blockchain creates an environment where the privacy of the system ultimately hinges on the tools employed by the user and the spying entity. Users who take few precautions for protecting their privacy will most likely leak enough financial information in order for it to be dangerous, assuming that the spying entity is analyzing the blockchain.

The next step is to get acquainted with how different Bitcoin wallet applications can help with privacy, and what to expect when using them. This will be covered in the next article in this series. In later articles, we will look at different cryptocurrencies and survey available exchange platforms in regions with restricted economic and political freedom.

Further reading

To completely understand what is going on under the hood of Bitcoin, Andreas Antonopoulos’ Mastering Bitcoin is an excellent resource which is translated into several languages.

More specifically, the Privacy page on the Bitcoin Wiki goes into much more depth on several of these topics and was very recently updated by Chris Belcher. The Blockstream block explorer was also patched recently to show “privacy ratings” for transactions and is now a good resource to learn more about what conclusions can be derived from transactions’ information.

Special thanks to Adam Gibson, Tomislav Dugandzic and Simon Bohlin for their thoughts and feedback to this article.

The essays in this series will form the basis for a report to be published by Coin Center, the leading cryptocurrency policy research and advocacy group based in Washington, DC.

The Zcash Foundation contributed funding for the project. The Zcash Foundation exists to build and support tools that enable privacy and autonomy, particularly with respect to people’s transactions and financial information. Privacy is important for numerous reasons — personal, medical, political, and more. For this reason, Zcash pioneers the use of zk-SNARKs, a novel form of zero-knowledge cryptography with strong privacy guarantees. Ultimately, the Zcash Foundation’s impact will come from serving the needs and workflows of real people, including those from many backgrounds and locations.

The views and opinions expressed by Eric Wall does not necessarily reflect the views of his employer or any affiliated entity.