Crypto Governance: The Startup vs. Nation-State Approach

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

Crypto Governance: The Startup vs. Nation-State Approach

Jack Purdy

Posted February 25, 2019

Intro

Humans like to argue. It’s in our nature.

Take any facet of human experience and you can find two people who disagree on it. Nowhere is this more prevalent than in the realm of governance, where we argue who should have power, who gets to make changes to the system, and how decisions are ultimately made. Given the magnitude of the impact governance has, it is easy to see how this became a highly controversial topic.

Now imagine a nascent industry full of highly intelligent people with strong opinions (and egos), where most of the debate occurs on globally accessible platforms. As you can imagine, there is no shortage of debates especially as it pertains to governing this industry. Welcome to crypto.

Crypto governance encapsulates the debates around how we coordinate to make decisions on changing the rules of a protocol. This could include anything from simple upgrades to changing the consensus mechanism to allocating block rewards. It involves many stakeholder groups such as node operators, network providers (miners), core developers, users, speculators, exchanges, and block explorers to name a few. These are diverse groups with varying incentives that frequently conflict with each other. For example, node operators want to keep block size low to reduce the costs of running a full node, while miners have incentives to increase the block size so each block includes more transactions and thus more transaction fees.

It is the interactions between these stakeholder groups that define what a blockchain is, its values and principles and how it evolves over time. This governance process shapes the imagined reality we create surrounding a network, and the value of a cryptoasset lies at this social layer .

Unsurprisingly, there has been a substantial amount of debate on the right way to govern cryptonetworks, which has created various thought-provoking theories. I believe much of the debate is misguided since ‘crypto’ is too general of a term to apply overarching ideas to. Jill Carlson explains it well:

Often investors attempt to apply the same priors and heuristics whether they are talking about bitcoin, petrocoin, or filecoin because they are all “crypto”. This would be akin to applying the same fundamental analysis to gold markets, sanctioned Venezuelan debt markets, and the pre-IPO valuation of Dropbox circa 2008.

In the same way we shouldn’t apply the same fundamental analysis for these assets, we shouldn’t analyze the governance of all cryptoassets in the same manner. We need to more accurately describe what is being governed in order to think about how it should be governed. In this analysis I’m going to delineate between base layer protocols from those further up the tech stack. The former should be governed like an established nation, while the latter an early stage startup.

The Startup Approach

“Moving fast enables us to build more things and learn faster. However, as most companies grow, they slow down too much because they’re more afraid of making mistakes than they are of losing opportunities by moving too slowly. We have a saying: ‘Move fast and break things.’The idea is that if you never break anything, you’re probably not moving fast enough” — Mark Zuckerberg,IPO Prospectus 2012

Zuck encapsulates this governance theory in the now famous mantra of “move fast and break things”. When you are looking at early-stage, user facing applications, you need to be responsive to customer needs. This requires the ability to rapidly iterate in order to meet these changing needs. If you move too fast and there is a bug, it is not the end of the world since there is not a tremendous amount of value in the network. You fix it and move on. The key is that the stakes are low so there aren’t grave consequences if something goes wrong. Failure will not result in large personal losses or a complete loss in faith in the idea ever working again.

Now what will this governance look like in crypto? It will likely operate like a well-oiled autonomous organization. A good example of a cryptonetwork that caters to this style of governance is Decred. (Note: Given Decred is aiming to be used as money, I am somewhat skeptical if this model makes sense for them, but regardless it is a general model I believe can be effective for more rapid improvements). Decred utilizes on-chain voting to allow DCR holders to participate in the governance process by staking tokens in order to obtain tickets. This lets stakeholders vote on matters such as how the treasury funds are spent to support development or whether consensus changes should be implemented via a hard fork. Placeholder summarized it best— ”Decred’s killer feature is good governance, and with good governance you can have any feature you want.” This thinking enables the necessary innovation needed to keep up with consumer needs and avoid a slow descent into irrelevance.

“Move fast and break things” succeeded in turning Facebook from a scrappy startup to a unicorn, but once they reached scale and had data on 2 billion people, that mantra was no longer appropriate. With that many people at risk, breaking things is no longer the goal or even acceptable for that matter. Rather the goal should be keeping the system secure, and unfortunately Facebook failed at this exposing the data of millions.

This brings us to our next approach that starkly contrasts with that of the early startup.

The Nation-State Approach

“We have to reinvent socialism. It can’t be the kind of socialism that we saw in the Soviet Union, but it will emerge as we develop new systems that are built on cooperation, not competition.” — Hugo Chavez to World Social Forum 2005

In January 2005, Hugo Chavez was embarking on a mission to re-shape Venezuela. That month he passed land reformallowing the government to seize over 6 million acres of private property. Two years later the government took over the last privately run oil field, with the banks following shortly after. The drastic measures taken by no means stop there, and they continue to this day.

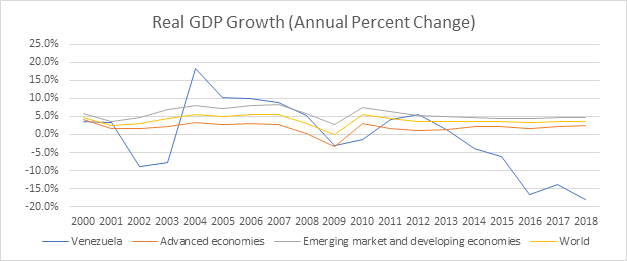

This example is not meant to make a political statement, but simply to demonstrate what can happen when a government attempts to make rapid changes that are unproven and largely experimental. This is a highly simplified illustration and there are a multitude of factors at play but that shouldn’t distract from showing the risks of this type of governance. The results of these actions are widely known and evidenced by the graph below.

Source: IMF

Source: IMF

When there are high stakes on the line to the underlying people, corporation, protocol etc. being governed, then the manner in which decisions and changes are made needs to optimize for the safety and security of those governed. No longer is the motive to innovate in order to outpace competitors because survival is the only way to win out.

Applying this to crypto, base layer protocols such as Bitcoin cannot afford to move fast at the detriment to security. When I refer to security here, I am talking about maintaining the well-being of bitcoin holders. This means not only ensuring the protocol doesn’t break, but upholding the censorship resistance, trust-minimized features that keep these holders secure. A 10x improvement in transaction speed or fees is not worth a 1% decline in security. If a critical bug is exploited or a users funds confiscated, it will be incredibly difficult to regain people’s trust in not just Bitcoin but the entire story they tell themselves surrounding a decentralized money. This is because technology such as Bitcoin is prone to the Lindy Effect, where the future life expectancy is proportional to its current age. Therefore, the longer it survives, the longer it is predicted to survive. If it fails, it not only starts from where it began but behind since its competitors (namely fiat) are now even more Lindy.

While it can be easy to get frustrated with the slow process to upgrade Bitcoin, it should be noted that extreme caution needs to be taken in changing base layer protocols where significant value rests on top. Valuable networks like Bitcoin need to be governed like national governments, where it is more important to reject unjust laws then to pass just laws. The more active governance is in a cryptonetwork, the more one requires trust to interact with it and the whole raison d’être of a decentralized currency is to minimize trust in others. Bitcoin developer Matt Corallo states:

Of Bitcoin’s many properties, trustlessness, or the ability to use Bitcoin without trusting anything but the open-source software you run, is, by far, king. More specifically, interest in Bitcoin appears to almost exclusively derive from a desire to avoid needing to trust some third party or combination of third parties.

This applies to other base layer protocols where there are expected to be valuable dapps built on top of it. In the same way one would be hesitant to incorporate in a country where the laws governing its business are prone to change at anytime, one should be wary to build dapps on top of a protocol that requires trust that the rules wont change in a detrimental fashion. While this is not an apples to apples comparison, I believe it is useful in highlighting the fact that high stakes situations where there is considerable value on the line necessitate a more ossified governance structure to mitigate risk for the governed.

Conclusion

Often times in crypto, we like to believe were reinventing the wheel. Accordingly we come up with unique heuristics and terminology to describe things. While in some cases this is true, often times we’re simply repurposing age old ideas to fit this new paradigm. I believe governance is one of these areas where we can learn from a lot from the past. For thousands of years humans have been organizing themselves in different groups to coordinate around shared goals in the form of nation-states, corporations and others social groups. Over time we have improved our standard of living as a result of organizing ourselves into these groups and evolving new ways to govern them. However, innovation in this front has been slow due to the difficulty in testing out alternate approaches (rightfully so) because of the high stakes on the line.

This is a big part of why I am so fascinated with cryptonetworks. They provide us a sandbox to try inventive new ways to organize human behavior by shifting how we incentivize participants. By carefully studying the failures and successes of different crypto projects I believe we can learn more about governance and at a faster pace then has ever been possible. A great analogy is comparing them to petri dishes, where we can test out different ideas on smaller chains and based on the results begin to implement bits and pieces into more established chains.

This shouldn’t be a black and white approach, but more of a spectrum based on the amount of value in the network and trust minimization required. On one end you have Bitcoin that needs to iterate slowly, preserving security at all costs and at the other you have experimental petri dishes that can test the efficacy of new models and look to incorporate them gradually down the tech stack as they grow stronger via the Lindy Effect.

To conclude, I believe instead of making overarching “laws” about crypto governance like Szabo’s Law, we need to take a more nuanced approach. My hope here was to start separating the governance of mission critical base layer from protocols from more application specific crypto projects. I look forward to expanding my thoughts on the subject in order to further delineate the ways in which cryptonetworks should be governed.

Much of my thinking was influenced by prior work that includes:

- Bitcoin Governance

- The Crypto Governance Manifesto

- Blockchain Governance 101

- Blockchain Communities and their Emergent Governance

- Blockchain Governance: Programming Our Future

- On Governance: Coordination, Layers, and Structural Integrity

- Cryptonetworks and Cities: Analogies

Other works linked previously in the article