Bitcoin Data Science (Pt. 3): Dust & Thermodynamics

Bitcoin Data Science (Pt. 3): Dust & Thermodynamics

By Dhruv Bansal

Posted December 18, 2018

This is part 3 of a series

- Bitcoin Data Science (Pt. 1): HODL Waves

- Bitcoin Data Science (Pt. 2): The Geology of Lost Coins

- Bitcoin Data Science (Pt. 3): Dust & Thermodynamics

tl;dr: We examine the history and future of dust: containers (UTXOs) of bitcoin that cost more to spend in fees than they hold.

The amount of dust in the blockchain is determined by the current UTXO set and transaction fee market. At peak fees (~ December 2017), between 25–50% of the UTXOs in the Bitcoin blockchain could have been called dust! At the same time, the amount of BTC contained in these dusty UTXOs was small: only a few tens of millions of dollars. So, depending on how you measure it, dust is either a huge problem or a trivial one. Either way, we discuss possible solutions for minimizing new dust and cleaning up existing dust.

Proof-of-work strongly anchors bitcoin in the physical world and makes it subject to the laws of thermodynamics. Energy expended by miners secures the blockchain, but this useful work is accompanied by an increase in entropy and the production of waste heat. If the Bitcoin blockchain were an engine, dusty UTXOs would be a part of the waste heat it exhausts. As no engine is perfectly efficient, Bitcoin will never stop making dust.

What is dust and where does it come from?

Bitcoin uses an accounting structure known as the Unspent Transaction Output or UTXO. The outputs of any Bitcoin transaction are new UTXOs and the inputs are existing UTXOs which are fully consumed by that transaction. On the blockchain, BTC is always “stored” in such UTXOs. See the previous post in this series on HODL Waves to learn more about Bitcoin’s UTXO distribution over time.

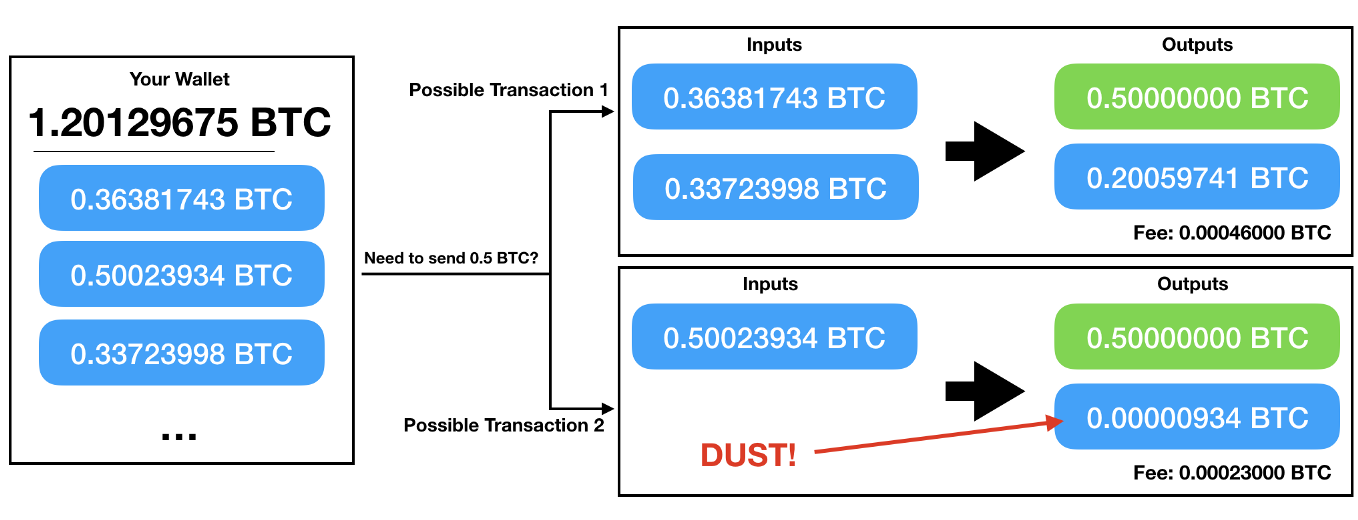

This diagram shows two possible ways a wallet might construct a transaction sending 0.5 BTC. The first transaction consumes two UTXOs and so costs more in fees. The second transaction only consumes one UTXO so is cheaper but creates a very low-balance change output. Wallet software must balance these trade-offs today with imperfect knowledge of how the fee market will change in the future. This is a difficult problem.

This diagram shows two possible ways a wallet might construct a transaction sending 0.5 BTC. The first transaction consumes two UTXOs and so costs more in fees. The second transaction only consumes one UTXO so is cheaper but creates a very low-balance change output. Wallet software must balance these trade-offs today with imperfect knowledge of how the fee market will change in the future. This is a difficult problem.

When a wallet constructs a transaction it must decide which UTXOs to consume as inputs. This may sound simple, but it’s really a difficult optimization problem. Jameson Lopp defines three simultaneous and conflicting goals wallet software authors must pursue:

- Support high transaction volume by keeping many UTXOs available in a wallet.

- Preserve privacy by being non-deterministic and masking which outputs are change.

- Minimize transaction fees, both now and later.

It’s clear that there is no “one size fits all” solution to this problem, and in fact the three broad optimization goals outlined above tend to be in direct opposition. —Jameson Lopp

Furthermore, wallet software is often generic, meant to be shared by many different types of users. Wallet authors do not know what future transactions a given user plans on making, nor how the market for transaction fees will develop.

This means that wallets can’t help but sometimes create low-balance, dusty UTXOs. UTXO management in wallets is a difficult optimization problem with no globally optimal solution for all users. This is the ultimate origin of dust.

What makes a UTXO dust?

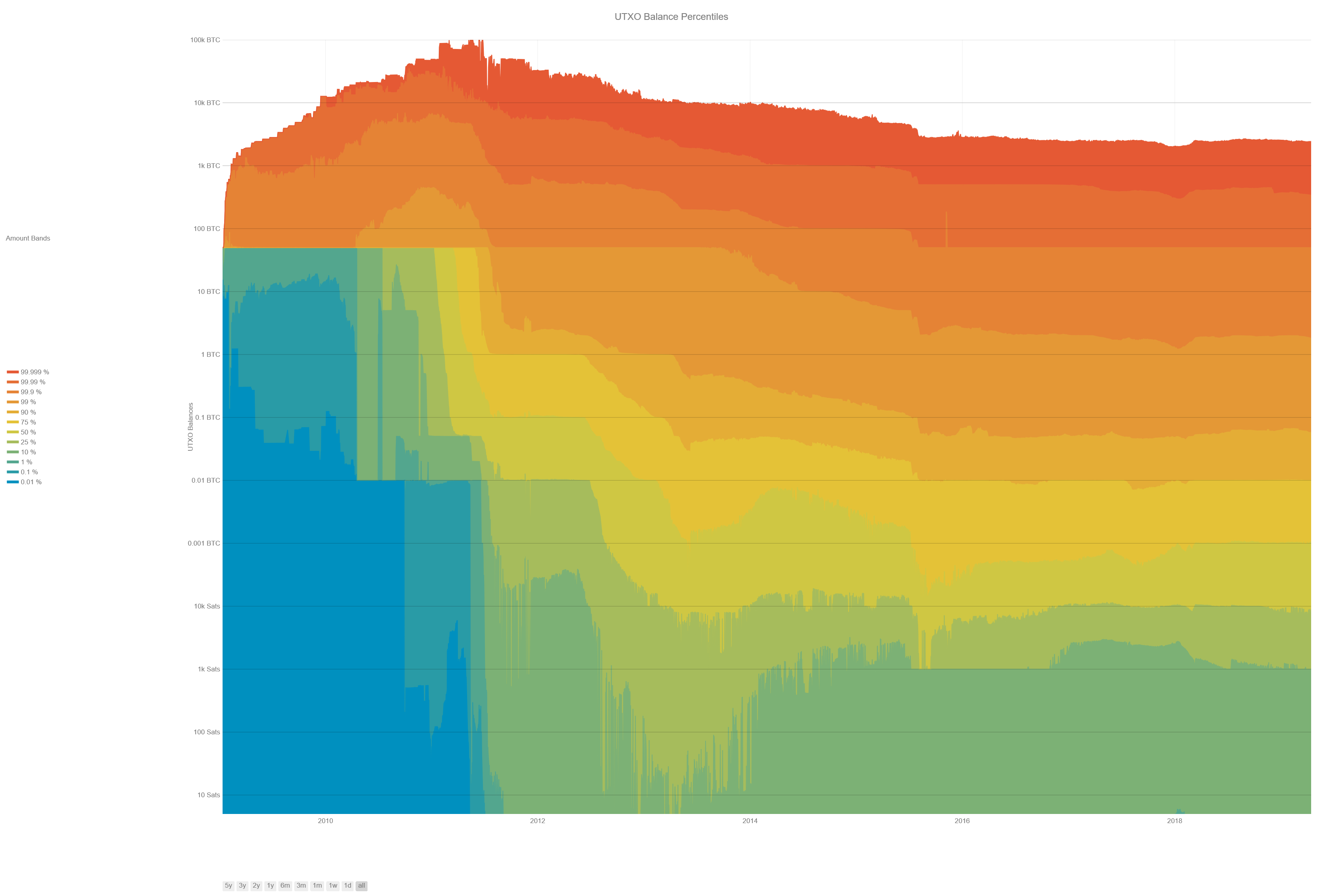

Intuitively, UTXOs with low balances are likely to be dust. The following plot shows the distribution of UTXO balances over time:

A plot of the distribution of UTXO balances over time. Cooler colors (blues and greens) represent low-balance UTXOs and warmer colors (oranges and reds) high-balance UTXOs. The percentiles we’ve chosen to plot highlight the lower and upper ends of the distribution. The range of UTXO balances is enormous: there are UTXOs at the upper end of the distribution containing thousands of BTC and some at the lower end containing fewer than 100 Satoshis (11–12 orders of magnitude!). [Direct Link]

A plot of the distribution of UTXO balances over time. Cooler colors (blues and greens) represent low-balance UTXOs and warmer colors (oranges and reds) high-balance UTXOs. The percentiles we’ve chosen to plot highlight the lower and upper ends of the distribution. The range of UTXO balances is enormous: there are UTXOs at the upper end of the distribution containing thousands of BTC and some at the lower end containing fewer than 100 Satoshis (11–12 orders of magnitude!). [Direct Link]

The plot does confirm that there are a good number of low-balance UTXOs, but can we define which of these low-balance UTXOs are dust more precisely?

Spending a UTXO in a transaction requires referring to that UTXO (by providing the ID of the transaction that created it as well as the order in which it appeared as an output in that transaction) as well as signing it with the required key(s). All of this takes a certain number of bytes to express, and miners must be compensated for bytes with transaction fees.

A transaction debits its transaction fees from its input UTXOs. This is usually not a problem as transaction fees are typically small compared to the sum of balances of all UTXOs they are consuming. But if a UTXO has a very low balance, or if transaction fees are very high, or the UTXO requires a very large number of bytes to spend, it is possible that a resulting output UTXO may cost more to spend than it contains.

We define the value density of a UTXO as its balance divided by the number of bytes required to spend it.

The value density of a UTXO measures how much BTC it contains per byte required to spend it.

With this definition, classifying a UTXO as dust requires comparing two things:

- the lowest transaction fee currently being accepted by miners

- the value density of the UTXO

Both quantities have units of Satoshi/byte, so they can be directly compared: if the value density of a UTXO is less than the lowest transaction fee being currently accepted by miners, that UTXO is currently dust. UTXOs can drop below, and later rise above, a “dust line” over time as the (often volatile) transaction fee market changes.

How many bytes does it take to spend a UTXO?

Classifying a UTXO as dust requires knowing how many bytes are required to spend it, but this number is not really well-defined: the number of bytes required to spend a UTXO on average decreases the more UTXOs are being spent in a single transaction, because they can all share header or segwit information.

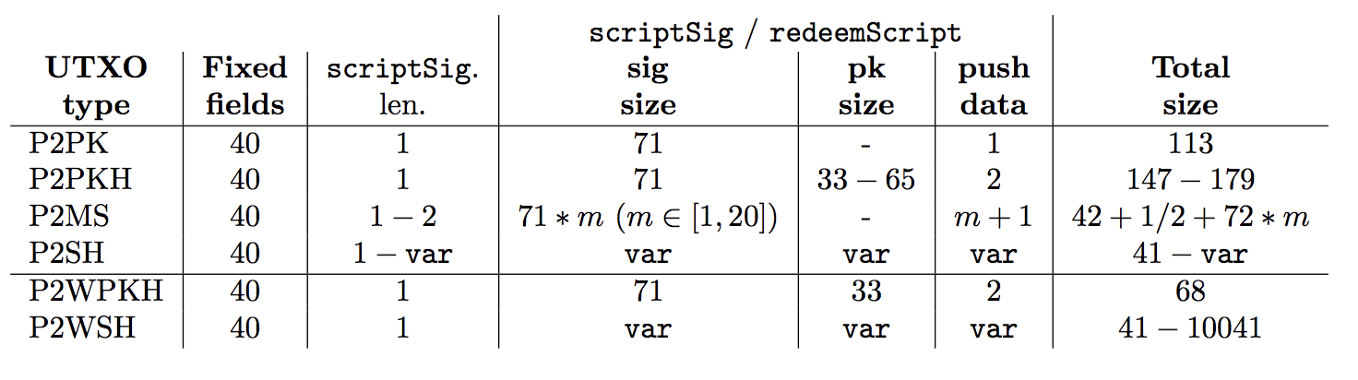

Regardless, we can at least make an arbitrary choice and ask for the number of bytes required to spend a UTXO assuming it is the single input in a transaction. The answer will depend on the type of the UTXO address. The following table summarizes this relationship:

Relationship between address type and the number of bytes required to spend a UTXO at that address. Copied from Table 3 of Pérez-Solà, Delgado-Segura, Navarro-Arribas, Herrera-Joancomart. “Another coin bites the dust: An analysis of dust in UTXO based cryptocurrencies” (2018) [Direct Link]

Relationship between address type and the number of bytes required to spend a UTXO at that address. Copied from Table 3 of Pérez-Solà, Delgado-Segura, Navarro-Arribas, Herrera-Joancomart. “Another coin bites the dust: An analysis of dust in UTXO based cryptocurrencies” (2018) [Direct Link]

The table above has definite sizes for “simple” address types such as P2PK and P2PKH. But for P2SH addresses in particular, it’s not possible to a priori calculate how many bytes are required to spend a UTXO from that address. Only a posteriori, once the redeem script for that address has been revealed in a transaction, can it be known how many bytes it takes to spend from that address.

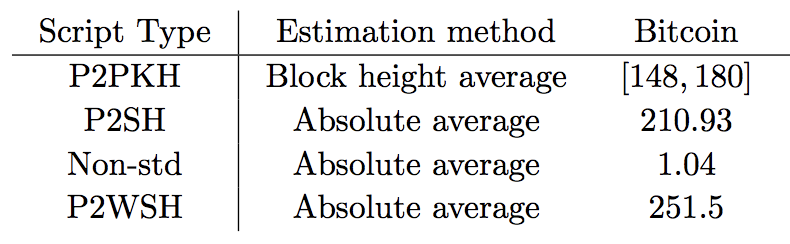

Nonetheless, most P2SH addresses are multisig addresses which have a predictable structure (once they are known to be multisig). And, we can extrapolate from the spends in blockchain history for many P2SH addresses:

Estimate of the number of bytes required to spend a UTXO from each of the given address types based on historical data. Copied from Table 6 of Pérez-Solà, Delgado-Segura, Navarro-Arribas, Herrera-Joancomart. “Another coin bites the dust: An analysis of dust in UTXO based cryptocurrencies” (2018) [Direct Link]

Estimate of the number of bytes required to spend a UTXO from each of the given address types based on historical data. Copied from Table 6 of Pérez-Solà, Delgado-Segura, Navarro-Arribas, Herrera-Joancomart. “Another coin bites the dust: An analysis of dust in UTXO based cryptocurrencies” (2018) [Direct Link]

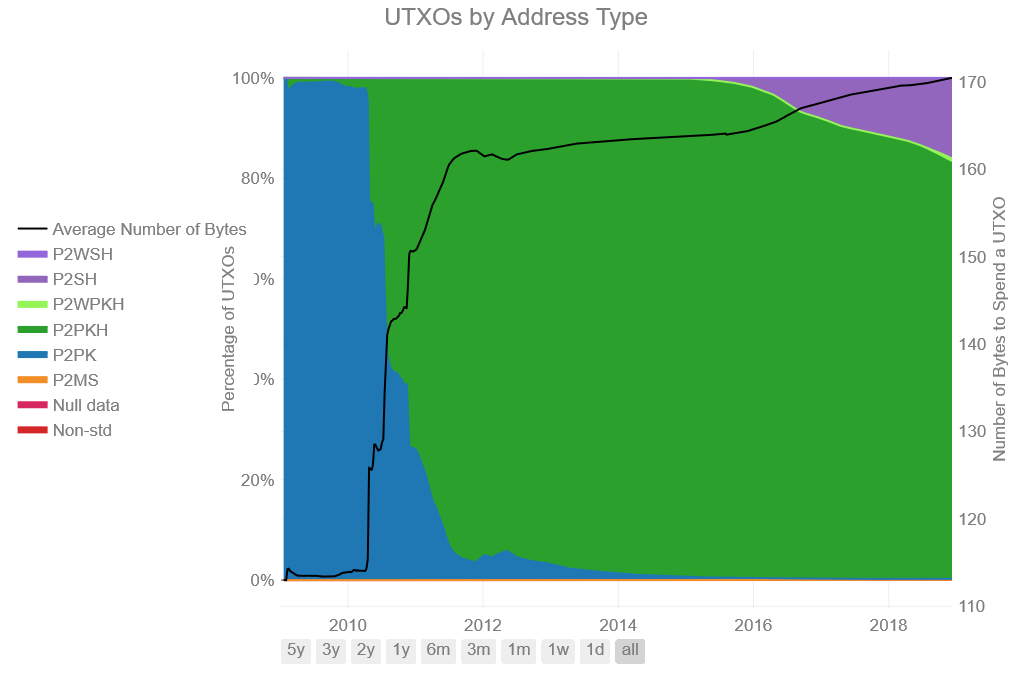

Given the distribution of UTXOs among address types, we could use the estimates in the above tables to calculate the average number of bytes required to spend a UTXO at any time. The following plot summarizes this data:

A plot of the distribution of Bitcoin’s UTXO set over address types through history. The black line shows the best estimate for the number of bytes required to spend the average UTXO at that time. The dominance of addresses has shifted from P2PK to mostly P2PKH and P2SH today. [Direct Link]

A plot of the distribution of Bitcoin’s UTXO set over address types through history. The black line shows the best estimate for the number of bytes required to spend the average UTXO at that time. The dominance of addresses has shifted from P2PK to mostly P2PKH and P2SH today. [Direct Link]

From the plot above, we make an estimate of 172 bytes to spend the average UTXO.

Note:By construction, this figure is an overestimate. Not only was the average number of bytes required to spend a UTXO lower than 172 bytes for most of Bitcoin’s history, but smart transaction batching could lower this estimate significantly.

How much dust is there?

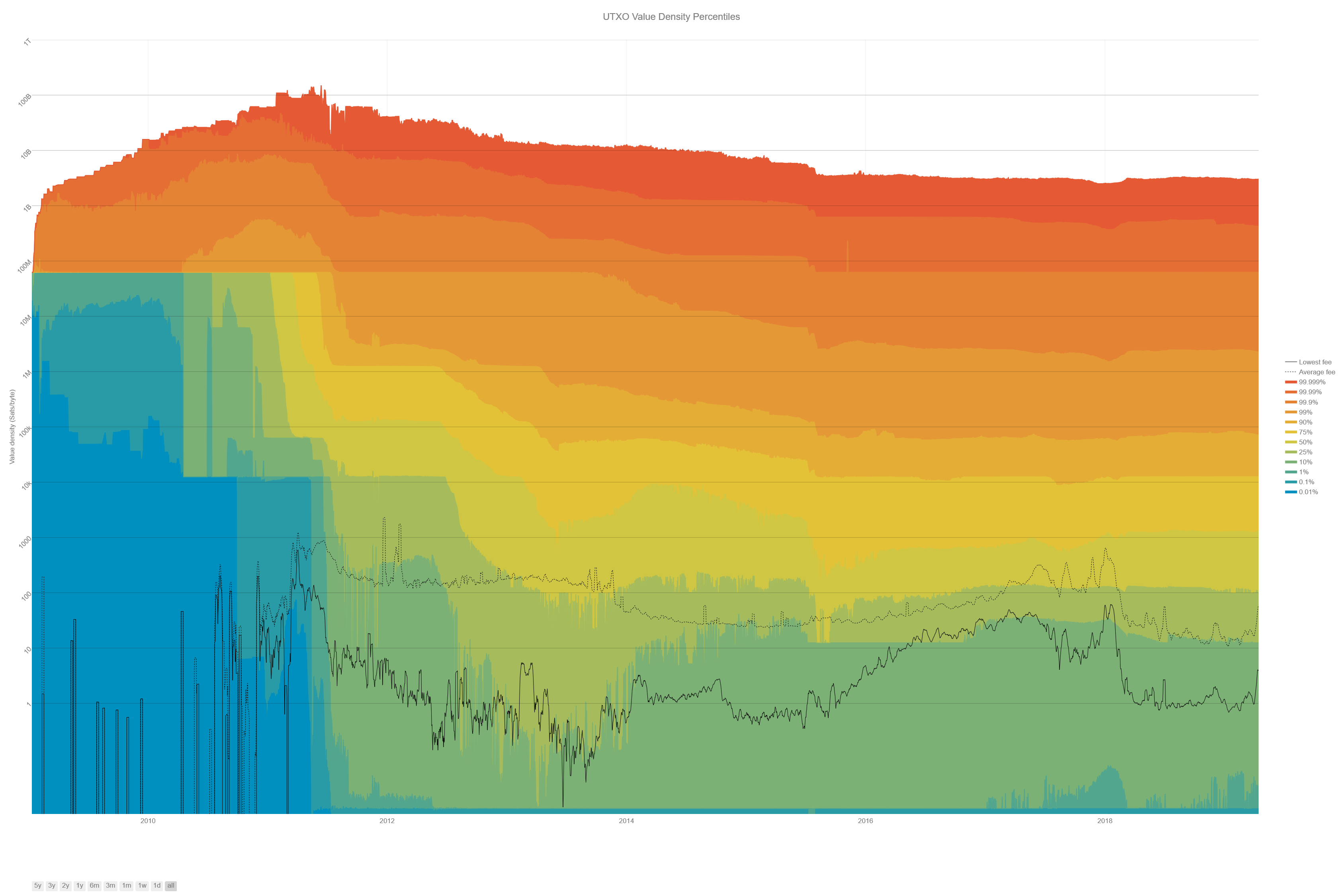

From the UTXO set at any block in Bitcoin’s history, along with the estimate of 172 bytes to spend a UTXO, we can construct the UTXO value density distribution by dividing each UTXO’s balance by the number of bytes required to spend it:

The colored bands show the value density at each percentile indicated in the legend. The dashed black line shows the average fee over time and the solid black line the lowest fee. UTXOs with value densities lower than the lowest fee cannot be spent, and those lower than the average fee are more difficult to spend. The plot assumes an average number of 172 bytes required to spend any given UTXO. [Direct Link]

The colored bands show the value density at each percentile indicated in the legend. The dashed black line shows the average fee over time and the solid black line the lowest fee. UTXOs with value densities lower than the lowest fee cannot be spent, and those lower than the average fee are more difficult to spend. The plot assumes an average number of 172 bytes required to spend any given UTXO. [Direct Link]

This plot is very similar to the previous plot of the UTXO balance distribution — it’s just rescaled by the number of bytes required to spend each UTXO (172). The units of this new distribution are Satoshi/byte, so we can directly compare it to the fee market at that block (black lines), something we couldn’t do with UTXO balances alone.

What does this plot show?

There’s a lot of dust!

During the high-fees market of late 2017, 15–20% of all UTXOs had value densities below the lowest fee of 50–60 Satoshi/byte, making them almost impossible to spend. 40–50% of all UTXOs had value densities below the average fee of 600–700 Satoshi/byte, making them harder to spend. This is a lot of dust!

The fee market dramatically cooled off through 2018. Today, 10–15% of UTXOs still have value densities below the average fees of 20–30 Satoshi/byte, and 3–5% of UTXOs have value densities below the lowest fees of 1–2 Satoshi/byte. There’s much less dust, but it’s still a lot.

All that dust isn’t worth much!

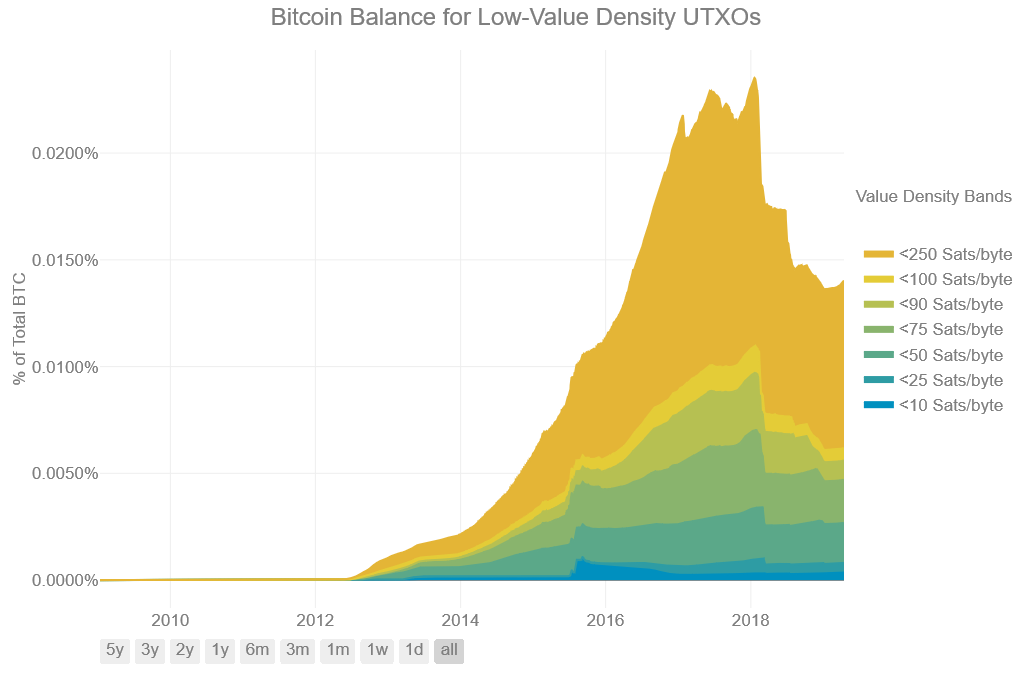

Let’s take a different perspective: a lot of the UTXOs by count may be dust, but how much bitcoin in total do these dusty UTXOs contain? Even though there are a lot of them, by definition they have low balances, so maybe in aggregate they don’t add up to much. The plot below shows the fraction of bitcoin contained in low-value-density UTXOs:

The colored bands show the fraction of BTC held by UTXOs of the given value density. Since the bulk of BTC is contained by high-value-density UTXOs, only the bands for low-value-density UTXOs (those likely to be dust) are shown. Zoom in on the last few months to see the the recent decrease in low-value-density UTXOs. The plot assumes an average of 172 bytes required to spend any given UTXO. [Direct Link]

The colored bands show the fraction of BTC held by UTXOs of the given value density. Since the bulk of BTC is contained by high-value-density UTXOs, only the bands for low-value-density UTXOs (those likely to be dust) are shown. Zoom in on the last few months to see the the recent decrease in low-value-density UTXOs. The plot assumes an average of 172 bytes required to spend any given UTXO. [Direct Link]

While there are many UTXOs which have low value densities, the plot above shows that the aggregate BTC held in dusty UTXOs is extremely small. Only 0.01–0.02% of BTC by value was dust, even at peak fees. At the then-market cap of ~ $225B, this amounted to $25–50M of dust.

The average fee today is much lower than it was in late 2017. Only 0.0005% of BTC is dust at today’s fees. And at today’s much lower market cap of ~ $65B, this represents only $300k of dust!

The value trapped as BTC dust has shrunk from as much as $50M in late 2017 to only $300k today.

Note: These figures are over-estimates. Smart transaction batching could reduce the average number of bytes required to spend a UTXO and therefore reduce our estimates above of both the number and value of dust UTXOs.

Can we reduce dust?

Bitcoin is a leaderless system. This makes it difficult to engineer top-down approaches to eliminate existing dust and reduce future dust production. We must instead rely upon incentives for users, miners, and businesses in the space. Do such incentives exist?

Exchanges & Other Businesses

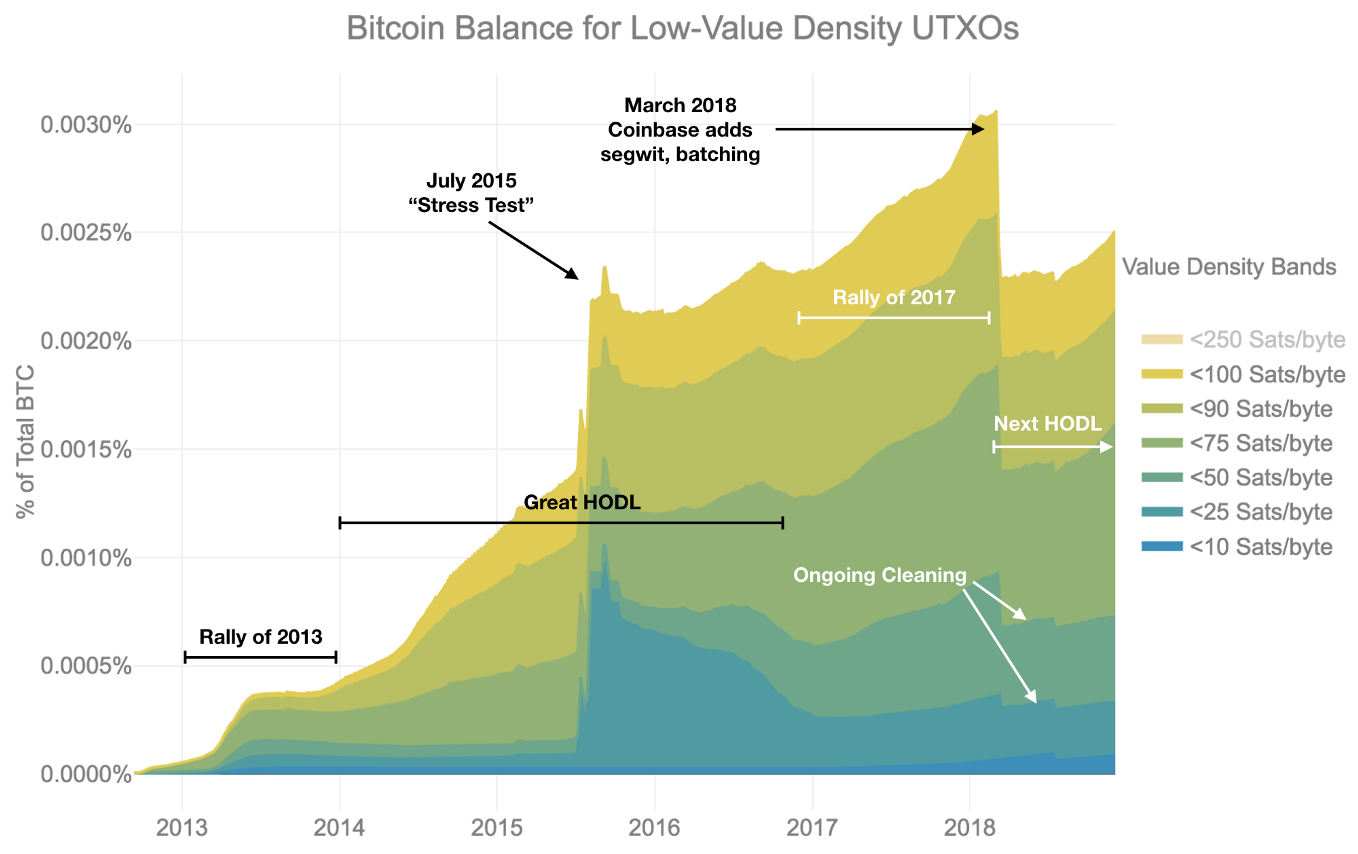

Yes, they do. While the collapsing price and fee market are chiefly responsible for the reduction in the amount of dust, in 2018 high-volume businesses such as exchanges, most notably Coinbase, instituted active dust reduction measures. The plot below of balances contained by low-value density UTXOs directly shows the impact of these active measures:

An annotated version of the plot of the fraction of BTC held by UTXOs of the given value density. The market as a whole acts to increase the amount of dust, whether slowly (HODLs) or quickly (rallies). Single actors can dramatically increase (“stress test” in 2015) or decrease (Coinbase in 2018) the amount of dust. But dust production never stops; note the recent increase and ongoing cleaning.

An annotated version of the plot of the fraction of BTC held by UTXOs of the given value density. The market as a whole acts to increase the amount of dust, whether slowly (HODLs) or quickly (rallies). Single actors can dramatically increase (“stress test” in 2015) or decrease (Coinbase in 2018) the amount of dust. But dust production never stops; note the recent increase and ongoing cleaning.

Businesses such as Coinbase had been creating a lot of dust and were inefficient in their usage of block space because they didn’t sufficiently batch customer transactions. Due to the popularity of major exchanges such as Coinbase during the rally of 2017, this behavior affected the rest of the Bitcoin network, and many rightly complained.

When fee markets pulled back in early 2018, Coinbase had both the incentive and the ability to reduce their existing dust footprint and their future production of dust. Batching transactions saves high-volume businesses such as Coinbase fees but also reduces their dust production. Antoine Le Calvez’s excellent When the Bitcoin dust settles analyzes this “UTXO consolidation” period, a spring cleaning of the UTXO set.

Do other constituencies in the Bitcoin ecosystem have the same combination of incentive and ability to reduce dust?

Users

Users are not directly affected by dust. They may create dust in aggregate due to inefficient wallet software they use, but few individual Bitcoin users have created much dust.

Users don’t like high fees, but dust doesn’t directly affected the fee market. Inefficient UTXO management which creates dust but also results in more, small transactions is a bigger cause of increasing fees. Users therefore only have a modest incentive to encourage dust reduction.

Even if they lack the incentive, do users have the ability to limit dust? After all, users have a lot of power in cryptocurrencies, as the UASF movement of 2017 proved. But dust is a shared problem, a tragedy of the commons, and so requires some coordinated solution. Users will need help from developers and/or exchanges and miners to clear any dust they own.

Individual users may be willing to “donate” their dust, and Bitcoin does provide mechanisms (e.g. ALL|ANYONECANPAY or NONE|ANYONECANPAY type signatures) for users to donate their dust. If wallets supported it, a socially-coordinated, public spring cleaning could be an interesting way to crowd-source funds for various user-chosen charities or projects benefiting the Bitcoin ecosystem.

Miners

Most miners ignore dust.

Miners in pools are just paid to hash; pool operators need to manage the UTXO set and deal with any bloat it contains, but they are also free to simply drop low value-density, dusty UTXOs from their mempools. No users are likely to spend them anyway! This would create an opportunity for scavenger-pools to pick up and attempt to mine these dust UTXOs, but this still requires users to act to spend them. Users may not notice or care.

Standalone miners or pool operators who do care about dust may choose to schedule a fee holiday — a time period where these miners will purposely allow zero-fee transactions which spend (only) low-value-density UTXOs, perhaps done during a spring cleaning. This will allow users to clean up their wallets while helping miners and node-operators to decrease the memory footprint of their UTXO set by a significant amount.

It’s possible that proposals such as BetterHash, which distribute the ability to choose transactions, might encourage more individual miners to leave traditional mining pools (where the pool operators determine the blocks to be mined) and to construct their own blocks. They might, then, have to deal with/care more about dust.

Miners could theoretically also refuse to mine transactions which create dusty UTXOs. But would they really be willing to sacrifice fee income in the short-term to prevent creating dust in the long-term? Given that pools dominate mining and that these pools don’t particularly care about dust, it seems unlikely.

Full-Node Operators

Full-node operators — those who backup the blockchain, relay, and verify transactions but don’t mine — also have some power over dust creation. The minRelayTxFee parameter in the bitcoind software allows node operators to set a minimum value density below which they will ignore/drop UTXOs (and the transactions creating them). To an extent, this setting already prevents the creation of extremely low-value density UTXOs — there would probably be more dust today if this setting had never been implemented.

But few node operators tune their configuration settings to this level of detail. Developers, because they choose the default settings that come with the bitcoind software, may have a lot more influence over how full nodes will operate in the wild.

Developers

In many ways, developers have the most power to limit dust production.

Developers write and document wallet software. Their trade-offs (and failures) in the face of a difficult optimization problem are the root cause of dust. New strategies and best practices, as they spread from wallet to wallet, driven by the demands of users, are the best way to decrease future dust production.

Developers define default node settings, which percolate through the network of full-node operators, miners, exchanges, and other businesses. This provides a sort of herd immunity against dust, filtering out dusty transactions from malicious or inefficient wallets.

Through grassroots campaigns (just like the UASF) developers can work directly with users and miners to build the social software necessary to schedule and operate spring cleanings and fee holidays.

By building second layers such as the Lightning Network, developers can even hope to transcend the problem of dust altogether.

Dust is Inevitable

But no constituency or collaboration can hope to eliminate dust production altogether. Despite the increasing awareness of dust during 2017 and the attempts to clean it in March 2018, dust keeps being produced:

- UTXOs with value-density <50 Satoshi/byte display a sawtooth curve of constant production followed by quick pullbacks: someone is actively making dust — but at least they’re cleaning up after themselves.

- There’s also already 10% more UTXOs (in dollar terms) with value-density <100 Satoshi/byte — these UTXOs aren’t dust today, but will turn to dust rapidly if the fee market rises again as it did in 2017.

Dust production is an inherent inefficiency of Bitcoin.

Does Dust Only Affect Bitcoin?

Not all blockchains use a UTXO model for transactions. Ethereum, for example, uses an account model.

- ETH deposited into an address from different transactions is commingled.

- Transaction fees are paid by the address broadcasting the transaction, not the address from which ETH is being transferred.

Both of these differences greatly reduce dust production but they don’t eliminate it. Ethereum developers also worry about dust and the bloating it causes in the Ethereum blockchain.

The production of dust, defined more generically as tokens which are uneconomical to spend, seems to be a common inefficiency across blockchains.

Thermodynamics of Blockchains?

The difference between a dusty or a normal UTXO is one of utility. A Satoshi held in a dusty UTXO is less useful than the same Satoshi held in a normal UTXO. But they’re otherwise identical on the blockchain.

The hashpower wagered by miners to secure the blockchain protects dusty UTXOs just as much as it protects more useful ones. This makes Satoshis held in dusty UTXOs seem even more useless, a literal waste of energy.

“Wasting energy” can be a sensitive issue for some in regards to Bitcoin. Some people already bemoan the energy used by proof-of-work to secure Bitcoin’s transactions. How much more strenuous would their objections be if they knew that large amounts of what Bitcoin secures won’t ever be used?

What is the energy efficiency of Bitcoin’s security?

Is there a concept of an energy efficiency for Bitcoin? The efficiency with which it uses hashpower to protect useful economic assets? One can trivially define an energy efficiency for a Bitcoin miner by treating it like a space heater — but is there a more interesting, blockchain-level definition of the energy efficiency fo the whole Bitcoin network? A definition which recognizes that Bitcoin’s efficiency is less than it might otherwise be because of the presence of dust?

Physics & Economics

Questions about energy efficiency can be stated in terms of thermodynamics and, thus, answered using the tools of physics.

In recent decades there have been many attempts by physicists to use their tools to model economic systems. Sometimes these attempts are beautiful in their simplicity and staggering in scope of their application: billions of dollars are managed by models derived from (or similar to) the Black-Scholes equation, which calculates option prices by analogy to the diffusion of heat through a physical substance.

Other attempts to integrate these fields (“econophysics”) feel like strange, isolated chimeras, rejected by both their parent disciplines.

Are blockchains an amenable subject for the quantitative analyses and theoretical models of physicists? Consider:

- Bitcoin, while still small in market cap (and dwindling!), now has 10 years of history and is already large enough to display interesting patterns across many magnitudes of users, investment, price, volume, and value.

- Blockchains are also distributed ledgers that record their data pseudo-anonymously, but with sufficient structure to analyze large-scale behavior in precise detail (see our HODL waves post).

- Most interestingly, by using large amounts of energy, Bitcoin becomes anchored in the physical world. This provides handholds for physicists to think about the thermodynamics of blockchains.

Blockchains are an unprecedented opportunity for combining insights from economics and physics.

Blockchain as Heat Engine

The combination of these properties suggests that we may want to take the casual statement “dusty UTXOs are a waste of energy” more seriously — indeed, more literally: UTXOs are a “waste” of energy because they aren’t doing any useful “work” for anyone. This lowers the efficiency we seek to measure.

Physicists defined a simple framework for understanding how useful heat, work, and waste (entropy) are related to efficiency in mechanical engines: the classical theory of thermodynamics.

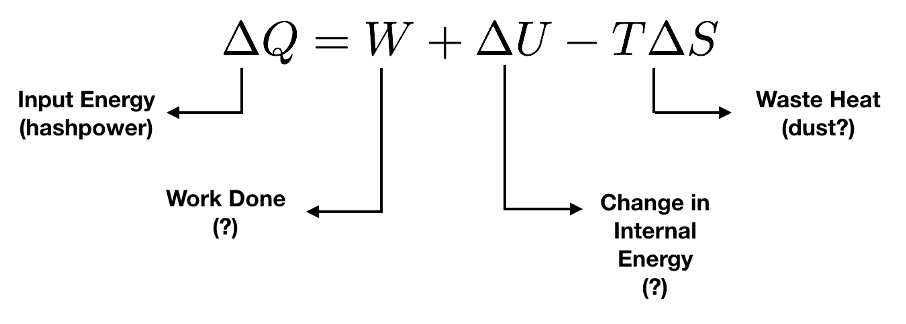

Thermodynamic equations like this one relate the input energy and work done by an engine to changes in its internal energy and the amount of entropy it produces. This particular equation is merely suggestive; it’s not clear how to even define some of these terms for blockchains.

Thermodynamic equations like this one relate the input energy and work done by an engine to changes in its internal energy and the amount of entropy it produces. This particular equation is merely suggestive; it’s not clear how to even define some of these terms for blockchains.

No classical engine is perfect; the extraction of useful work is always accompanied by an increase in entropy, usually manifested as waste heat in the system: a Joule of energy distributed among the molecules of air and fuel in the reaction chamber is more useful than the same Joule of energy present as random vibrations among molecules in the hot exhaust of the engine. An engine’s efficiency is the degree to which an engine avoids producing waste heat in favor of useful mechanical work.

Dusty UTXOs aren’t useful, but they are being secured anyway, just as waste heat in the exhaust of the engine isn’t useful but produced anyway. And just as engineers have designed clever systems to avoid the production of waste heat and to shed it quickly, blockchain engineers are developing smarter wallet software, and blockchain companies are “cooling off” their own dust in an effort to increase the efficiency of the chain (in particular, cooling UTXOs is done in order of their “grain-size” — businesses clean higher-value density dust before lower-value density, as shown by Antoine Le Calvez in When the Bitcoin dust settles).

Making the analogy between dust and waste heat more precise is challenging. The same thermodynamic laws governing engines apply to any system — including a proof-of-work based blockchain. The difficulty is in applying their definitions. What is “work” in the context a bitcoin transaction? How does one measure a blockchain’s “internal energy”? Is Bitcoin in equilibrium? Treating the system as just a bunch of computers making physical waste heat is true, but uninteresting and overly reductive. Is there a level of abstraction at which the domain data of Bitcoin (transactions, UTXOs, price, volume, fees, &c.) can be thought of as a thermodynamic system?

If we had a better theory about the thermodynamics of proof-of-work blockchains, we might be able to answer such questions and define “energy efficiency” for Bitcoin along with a methodology for calculating it from real-world data on energy usage, transaction volume, UTXO creation, price data, fee markets, etc.

A thermodynamic theory of blockchains would be an advance in both economics and physics. Answering the question, “Where does the energy miners input into hashing Bitcoin go?” in a way that helps us understand the economics of Bitcoin using the language of thermodynamics could be a very powerful new framework for understanding the world.

[Source]

[Source]

This post is the third in a series using data science to tell stories about Bitcoin. It analyzes how much “dust” — difficult to spend UTXOs — exists in Bitcoin’s blockchain.

You might also enjoy