Bitcoin bites the bullet

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

Bitcoin bites the bullet

Some of its most puzzling tradeoffs explained

By Nic Carter

Posted June 19, 2019

In the matter of reforming things […] there is a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, […] a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.” – G.K. Chesterton, The Thing: Why I am a Catholic

What’s wrong with Bitcoin is that it’s ugly. It is not elegant. –Gwern Branwen , Bitcoin is Worse Is Better

It is sometimes said that there are no free lunches in cryptocurrency design, only tradeoffs. This is a frequent refrain from exasperated Bitcoiners seeking to explain why hot new cryptocurrency probably can’t deliver 10,000 TPS with the same assurances as Bitcoin.

Today, as hundreds of alternative systems for permissionless wealth transfer have been proposed and implemented, it’s worth contemplating why exactly Satoshi built Bitcoin as s/he did, and why its stewards oriented the project in such a deliberate way.

Here I’ll argue that its features were not arbitrarily selected, but chosen with care, in order to create a sustainable and resilient system that would be robust to a variety of shocks. In many cases, this required choosing an option which appeared unpalatable on its face. This is what I mean by biting the bullet. It is evident to me that that, when faced with two alternatives, Bitcoin often selects the less convenient of the two.

This is confusing to many — hence “I just heard about Bitcoin and I’m here to fix it” syndrome — but when long-term consequences are taken into account, the design considerations often make sense.

As a consequence, Bitcoin is saddled with a variety of features which are cumbersome, onerous, restrictive, and impair its ability to innovate, all in service of a longer-term or more overarching goal. In this article I’ll cover a few of the tradeoffs where Bitcoin opted for the unpopular or more challenging path, in pursuit of an ambitious long-term objective:

- Managed/unmanaged exchange rates

- Uncapped/capped supply

- Frequent/infrequent hard forks

- Discretionary/nondiscretionary monetary policy

- Unbounded/bounded block space

Managed/unmanaged exchange rates

One of the commonest critiques of Bitcoin, often emanating from central bankers or economists, is that it is not a currency because it lacks price stability. Typically, the mandate of central bankers is to optimize for relatively stable purchasing power (although currency depreciation at two percent a year is considered tolerable in the US) and other objectives like full employment. Lacking any mechanism to manage exchange rates, Bitcoin is considered a priori not a currency. Implicit in the conventional view of what constitutes a sovereign currency is some notion of management; just ask Christine Lagarde:

For now, virtual currencies such as Bitcoin pose little or no challenge to the existing order of fiat currencies and central banks. Why? Because they are too volatile, too risky, too energy intensive, and because the underlying technologies are not yet scalable.

Or Cecilia Skingsley, deputy director of the Swedish central bank:

I have no problem with people using [bitcoin] as an asset to invest in, but it’s too volatile to be used as currency.

Of course, Bitcoin’s volatility cannot be managed; against the backdrop of a scarce supply, price is almost exclusively a function of demand. Bitcoin is almost perfectly inelastic in its supply, and so waves of adoption manifest themselves in gut-wrenching price gyrations. This contrasts with sovereign currencies where the central bank pulls various levers to ensure relative exchange rate stability.

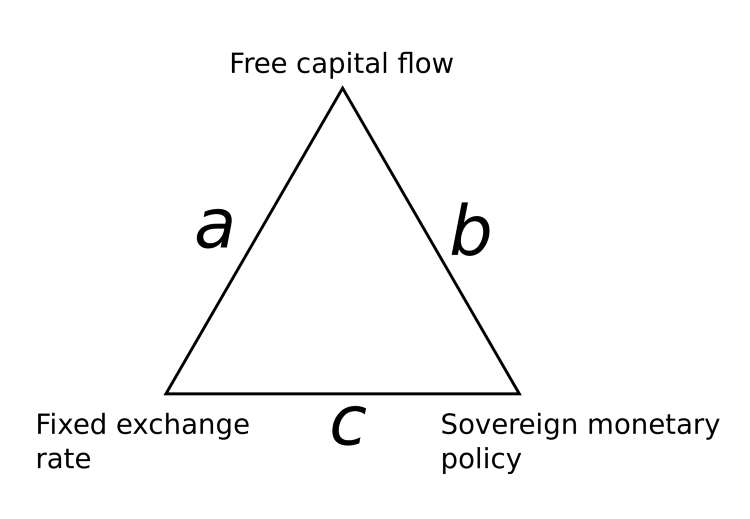

The tradeoffs inherent in monetary policy are often expressed as a trilemma, where monetary authorities can select two vertices but not all three. To put this another way, if you want to peg your currency to something stable (usually another currency like the US dollar), you have to control both the supply of your currency (sovereign monetary policy) and the demand (the flow of capital). China is a good example, taking side C: the Renminbi is soft-pegged to the dollar and the PBoC wields sovereign monetary policy; these necessarily require the existence of capital controls.

The ‘impossible trinity’ of monetary economics

The ‘impossible trinity’ of monetary economics

The Bank of England was infamously reminded of this constraint in 1992 when Soros and Druckenmiller realized that its peg with the German Deutschmark was fragile and could not be defended in perpetuity. The BoE had to admit defeat and allow the Pound Sterling to float freely.

A more contemporary example of this constraint is Hong Kong’s current travails with its currency which is soft-pegged to the US dollar. Unfortunately for Hong Kong, the US dollar has strengthened considerably in recent years, and so the monetary authority has been faced with the unenviable challenge of meeting an appreciating price target. A capital outflow from HK to the US has compounded the difficulty.

Hong Kong selected option A on the graphic, giving up monetary authority in exchange for a free flow of capital and a pegged exchange rate. If they lose the peg they will regain monetary sovereignty (the ability to untether their interest rate policy from the US Fed’s) while retaining open capital flows.

So there is an inescapable tradeoff when it comes to monetary policy. No state, no matter how powerful, is immune to it. If you want to index your currency to that of another state, you either become its monetary vassal, or you undertake the herculean task of stopping your citizens from exporting funds abroad.

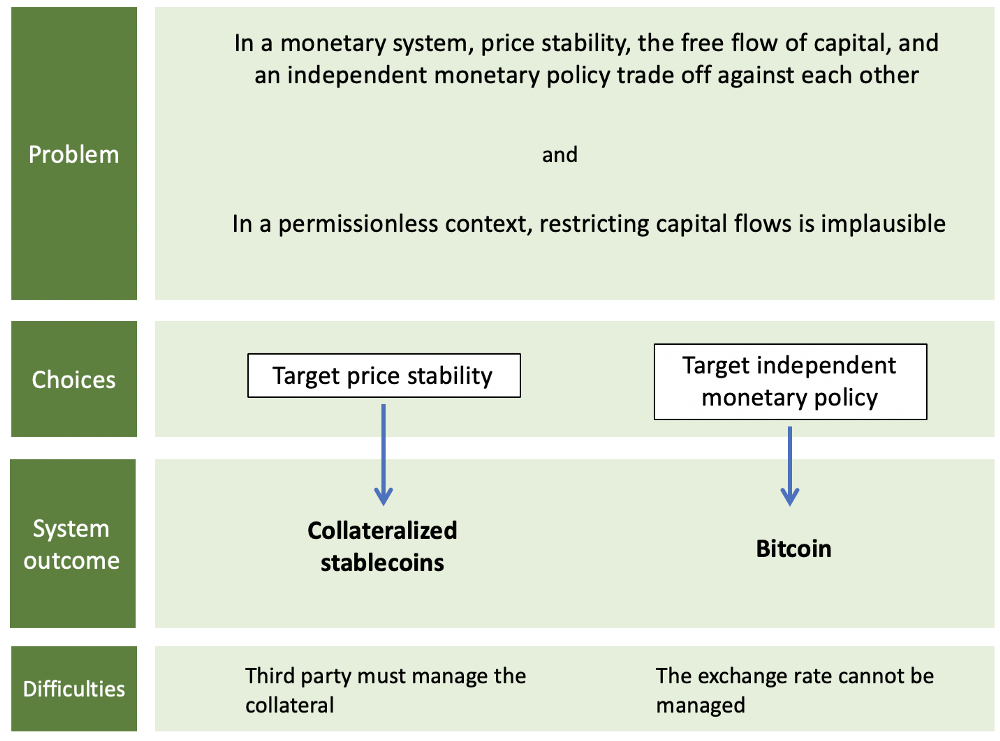

So to a monetary economist, the fact that Bitcoin cannot manage its exchange rate should be quite unsurprising. It is an upstart digital nation, designed to render capital easily portable (so capital controls are out of the question), and has no authority capable of managing a peg. Bitcoin is able to exercise extreme supply discretion thanks to its asymptotic money supply targeting, but has no mechanism whatsoever to control capital flows, and naturally has no central bank to manage rates. Compare this to Libra, Facebook’s new cryptocurrency, backed by a basket of sovereign currencies. Arguably, it can never become truly permissionless, as some entity must always manage the basket of securities and currencies backing the coin.

Bitcoin bites the bullet by letting its exchange rate float freely, opting for a system design with no entity tasked with managing a peg and with sovereign monetary policy. Volatility and future exchange rate uncertainty is the price that users pay for its desirable qualities — scarcity and permissionless transacting. The bullet bitcoin bites is an unstable exchange rate, but in return it frees itself from any third party and wins an independent monetary policy. A decent trade.

Uncapped/capped supply

One of the most heated debates within the cryptocurrency industry is whether it is possible to have a genuinely finite supply or not. This tends to turn on one’s view as to whether fees or issuance should pay for security in the network. So far, no permissionless cryptocurrency has found a cost-free way to secure the network (unless you believe what the Ripple folks have to say…). Since, all things equal, holders benefit from less issuance rather than more, if you believe that transaction fees can suffice to pay for security, you might find a fee-driven security model preferable.

Indeed, Satoshi believed that Bitcoin would have to wean itself from the subsidy and transition entirely to a fee model in the long term:

The incentive can also be funded with transaction fees. […] Once a predetermined number of coins have entered circulation, the incentive can transition entirely to transaction feesand be completely inflation free.

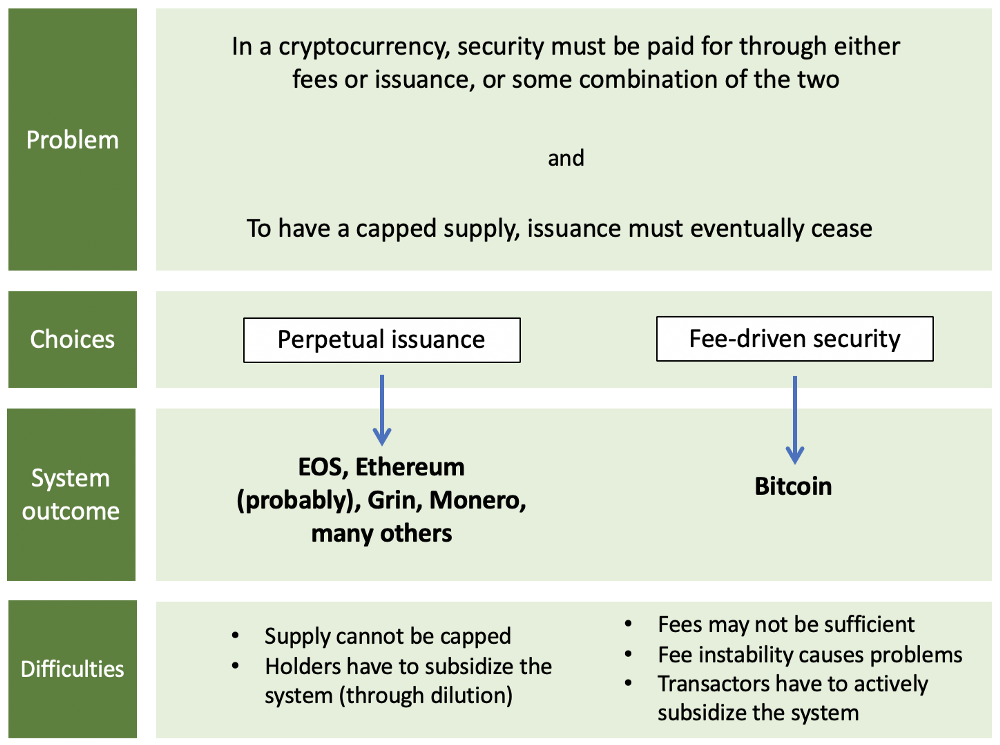

Ultimately, the choice in a permissionless setting, where security must be paid for, is quite stark. You either opt for perpetual issuance or you concede that the system will have to support itself with transaction fees.

Given the popularity of perpetual issuance systems in new launches, a rough consensus appears to be emerging that attaining sufficient volume for a robust fee market to develop is too challenging an objective for an upstart chain.

However, Bitcoin, in typical bullet-biting fashion, selects the less palatable of the two choices — capped supply and a fee market — in order to obtain a trait its users find desirable: genuine, unimpeachable scarcity. Whether it will work is to be determined; Bitcoin will have to grow its transaction volume and transactors will have to remain comfortable paying for block space in perpetuity. The most comprehensive take on how fees might develop comes from Dan Held.

Bitcoin’s Security is Fine Fears over the declining block reward are overblown blog.picks.co

While no one quite knows how Bitcoin’s fee model will shake out, the fact that Bitcoin has a robust fee market already with fees accounting for about nine percent of miner revenue (at the time of writing) is encouraging.

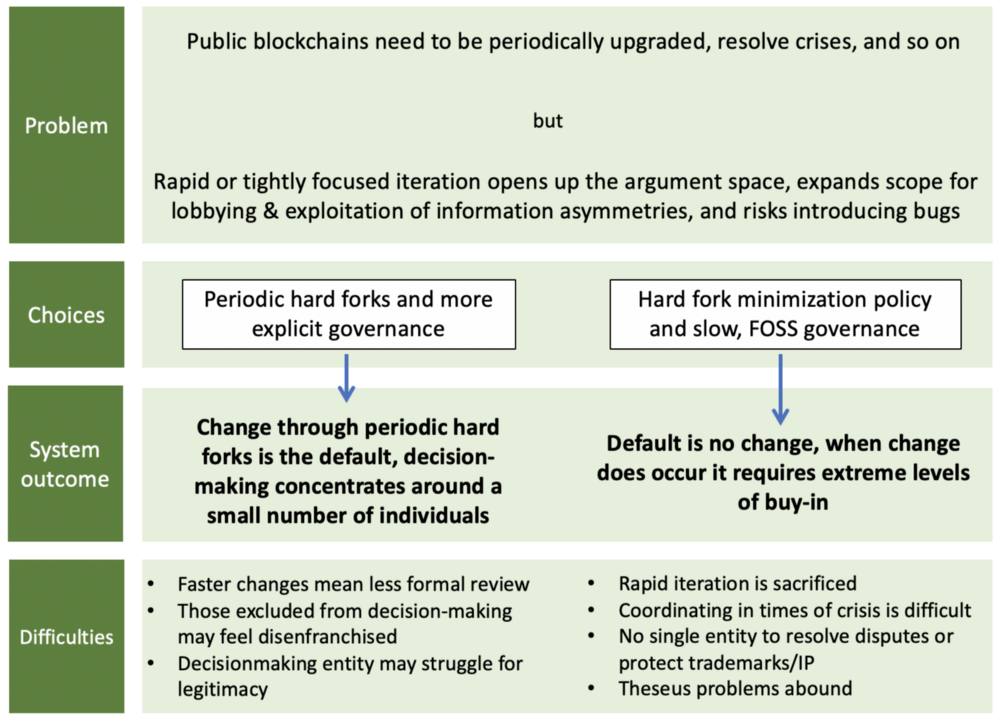

Frequent/infrequent hard forks

The frequency of forking among cryptocurrencies tells you a great deal about their design philosophies. For instance, Ethereum was positioned as the more innovative counterpart to Bitcoin for a long time, as it had certain advantages like a (functioning) foundation, a pot of money which could be used to finance developers, and a social commitment to rapid iteration. Bitcoin developers, by contrast, have tended to de-emphasize development through forks and generally aim to proceed through opt-in soft forks, like the SegWit upgrade. (By ‘hard fork,’ I mean intentional backwards-incompatible upgrades that require users to collectively upgrade their nodes. In a hard fork situation, legacy nodes might become incompatible with the new ruleset.)

In my opinion this often comes down to fundamental conflict of visions in how development should be organized; Arjunand Yassine cover the topic well in their essay.

A Conflict of Crypto Visions Why do we fight? A framework suggests deeper reasons medium.com

As stated, some cryptocurrency developers have adopted a policy of regular hard forks to introduce upgrades into their systems. A regular hard fork policy is virtually the only way to frequently upgrade a system where everyone must run compatible software. It’s also risky: rushed hard forks can introduce covert bugs or inflation, and can marginalize users who did not have sufficient time to prepare. Poorly-organized hard forks in response to crises often lead to chaos, as was the case with Verge and Bitcoin Private. Major blockchains like Ethereum, Zcash, and Monero have adopted a frequent hard fork policy, with Monero operating on a six-month cadence, for instance.

Forking with frequency is, as with many of the design modes in this post, expedient, but it comes with downsides. It tends to force decision-making into the hands of a smaller group — because the slow, deliberative governance style that characterizes Bitcoin Core is ill-suited to rapid action — and it introduces attack vectors. Developers in charge of forking can reward themselves and their inner circle at the expense of users; for instance, by creating a covert or explicit tax which flows to their coffers, or altering the proof of work function so it only works with hardware they own. As with everything in the delicate art of blockchain maintenance, concentrating power comes at a cost.

Something to note is the fact that all blockchains which are more decentralized in their administration suffer from so-called Theseus problems. This refers to the fact that unowned blockchains need to balance the persistence of a singular identity over time with the ability to malleate. I discuss the topic at length here:

Ultimately public blockchains that have no single steward that is responsible for resolving disputes have to face these problems of Theseus. So the option on the right is a painful one. But again, it is a tradeoff that Bitcoin is happy to make.

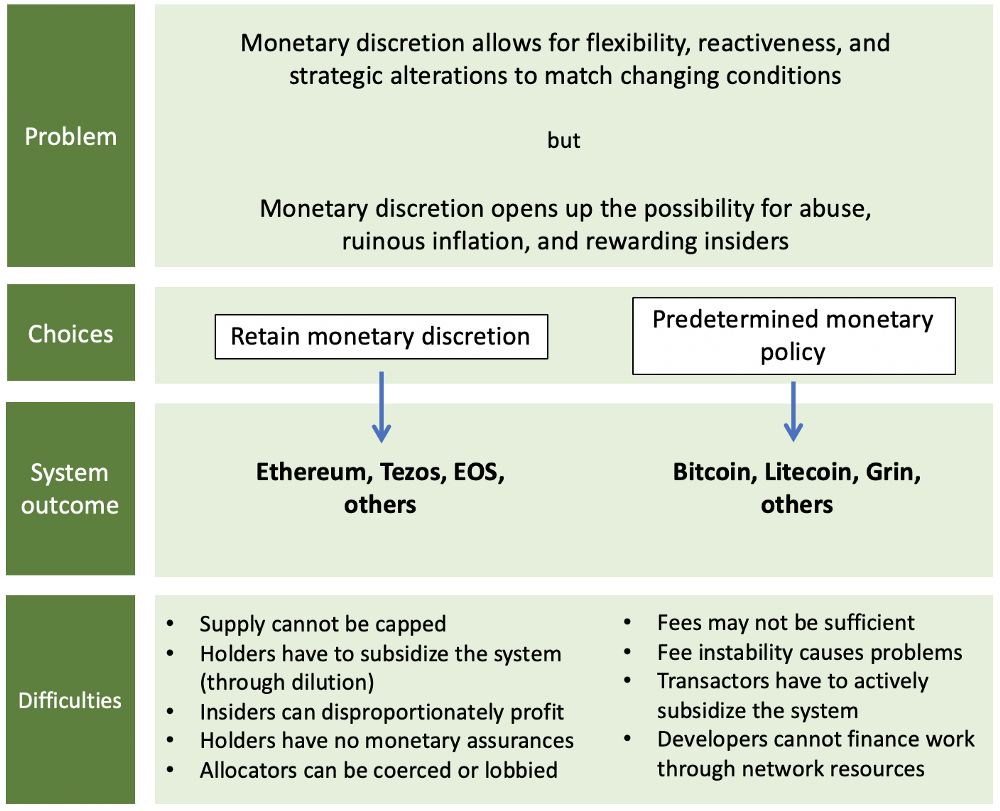

Discretionary/nondiscretionary monetary policy

If you are an artist or engineer, you may have noticed that restriction is the mother of creativity. Narrowing the design or opportunity space of a problem often forces you to discover an innovative solution. In more abstract terms, if you have more available resources, you are less likely to be careful with how you deploy them, and more likely to be profligate.

Russian composer Igor Stravinsky said it well:

The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one’s self. And the arbitrariness of the constraint serves only to obtain precision of execution.

There is a small but burgeoning literature reinforcing this phenomenon. Mehta and Zhu (2016) investigate the “salience of resource scarcity versus abundance,” finding:

[S]carcity salience activates a constraint mindset that persists and manifests itself through reduced functional fixedness in subsequent product usage contexts (i.e., makes consumers think beyond the traditional functionality of a given product), consequently enhancing product use creativity.

Examples of this phenomenon abound. In venture financing, over-funding a startup often paradoxically leads to its failure. This is why startups are encouraged to be lean — it imposes discipline and forces them to focus on revenue generating opportunities rather than meandering R&D or time wasted at conferences. In more mature companies, an excess of cash often leads to wasteful M&A activity.

I would venture that the same phenomenon holds in the context of nations with regards to their monetary policy. If it is easy to raise capital through dilution (this is essentially how inflation works for sovereign governments), it is easy to finance wasteful ventures, like overseas conflicts. Similarly, in cryptocurrency, discretionary inflation is often presented as a positive — it is often bundled with governance and it gives developers the ability to finance operations, marketing, and so on. Quite simply, enabling discretion in monetary policy creates a profound abundance that the project administrators can exploit. This however comes with drawbacks: it opens the door to rent-seeking, exploitation, and wealth redistribution, all of which harm the long-term integrity of the project.

In many cases, monetary discretion — the ability to inflate supply at will when required — is presented as an innovation relative to Bitcoin. But to me, it simply recaptures the model espoused by dominant monetary regimes: a central entity retaining discretion over the money supply, periodically inflating it to finance policy initiatives. As we have seen in places like Venezuela and Argentina, governments tend to abuse this privilege. Why would cryptocurrency developers be any different?

Bitcoin’s predetermined supply, a product of its radical commitment to resisting monetary caprice, is its solution to the problem. A grotesque, arrogant solution, to many opponents, but one that is critical to the design of Bitcoin. By holding this variable fixed, and iterating around it, Bitcoin aims to provide lasting, genuine scarcity and eliminate humans from decision-making altogether. This may come at a great cost. Opponents deride Bitcoin’s “high” fees, although stable fee pressure will be ultimately necessary for security as the subsidy declines. And unlike nimbler projects, Bitcoin cannot fill its coffers from the spoils of inflation.

I’ll note that some of the projects in the left hand column have not actually arbitrarily inflated supply to achieve policy objectives, but they have essentially written that possibility into the social contract — that supply is a lever which can be pulled if the stakes warrant it.

It is quite simply convenient to reinsert monetary discretion into the system to finance the acquisition of mercenary developers, acquire hype with marketing, and support the operations of a single corporate entity which can allocate resources. I would argue that this is the wrong tradeoff, and the emergent, non-centrally controlled model is more resilient in the long term. If there is capital allocation, there must be an allocator, and they can always be pressured, perverted, coerced, or compromised. Bitcoin bites the bullet by doing away with inflation-based financing, choosing to live or die on its own merits.

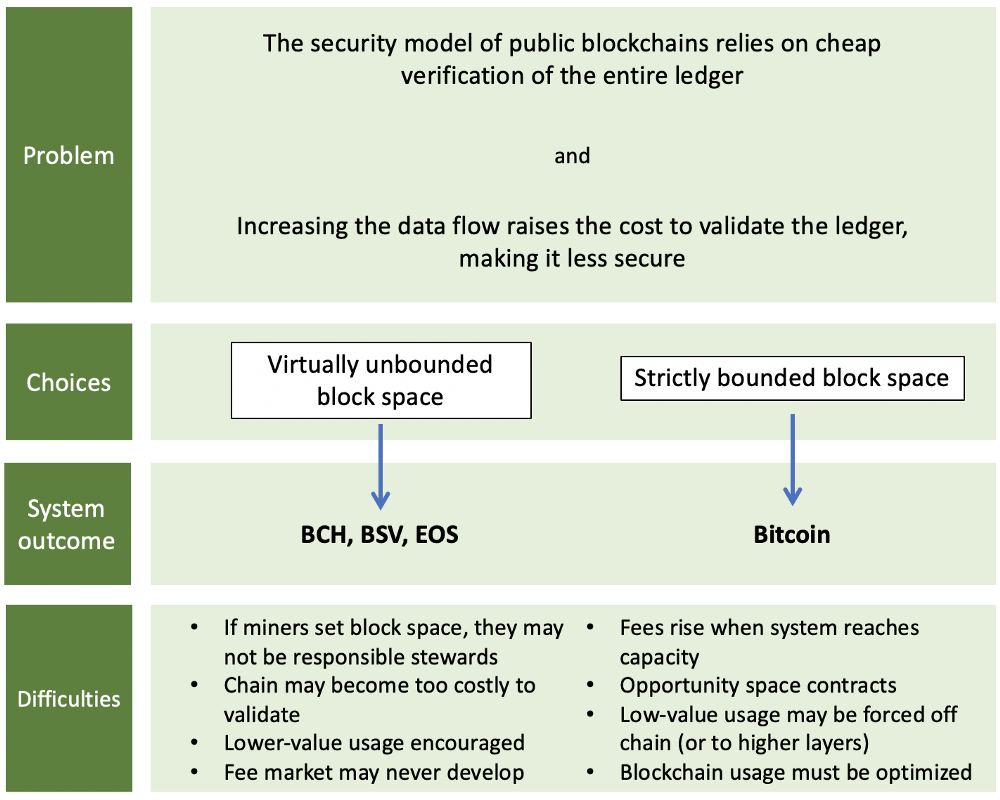

Unbounded/bounded block space

The block space debate can also be understood in similar terms to the restricted/unrestricted point made above. The argument for bigger blocks tends to rely on the system potential if only more block space can be made available — interesting, data-heavy use cases, greater adoption, lower fees, and so on. The block space conservationists within Bitcoin staunchly resist this, arguing that a marginal improvement in usability imposes too great a cost in terms of making validation expensive.

The standard proposal in forks of Bitcoin like Bitcoin Cash or BSV is that miners, not developers would set the blocksize cap — well above Bitcoin’s effective ~ 2 mb cap (the 1 mb cap is a myth). However, this is problematic, as block space is an unpriced externality. It doesn’t cost anything to a miner to raise the cap. In fact, larger miners may prefer larger blocks as they disadvantage smaller miners. However, an ever-growing ledger — with all the increased costs of validation that accompany it — imposes a very real cost on verifiers, node operators who want to verify inbound payments and ensure that the chain is valid. Miners’ incentives are not aligned with the entities that their block sizing affects.

Faced with this externality, Bitcoin opts for what might appear an unpalatable choice: initially capping the block size at 1 mb, now capping it at 4 mb (in extreme, unrealistic cases — more realistically, about 2mb). The orthodox stance in Bitcoin is that bounded block space is a requirement, not only to weed out uneconomical usage of the chain, but to keep verification cheap in perpetuity.

Additionally, simple observations from economics make it clear what the outcome of an uncapped block size will be. Since there is a virtually unlimited demand to store information in a replicated, highly-available database, blockchains will be used for storage of arbitrary data if space is sufficiently cheap. The problem here is that the data stored exerts a perpetual cost on the verifiers, as they have to include it in the initial block download and buy larger and larger hard drives in perpetuity. (Ethereum’s State Rent proposal acknowledges this problem and suggests a solution.)

Bitcoiners, far from lamenting ‘high’ fees, embrace them: making ledger entries costly renders a certain breed of spam expensive and unfeasible.

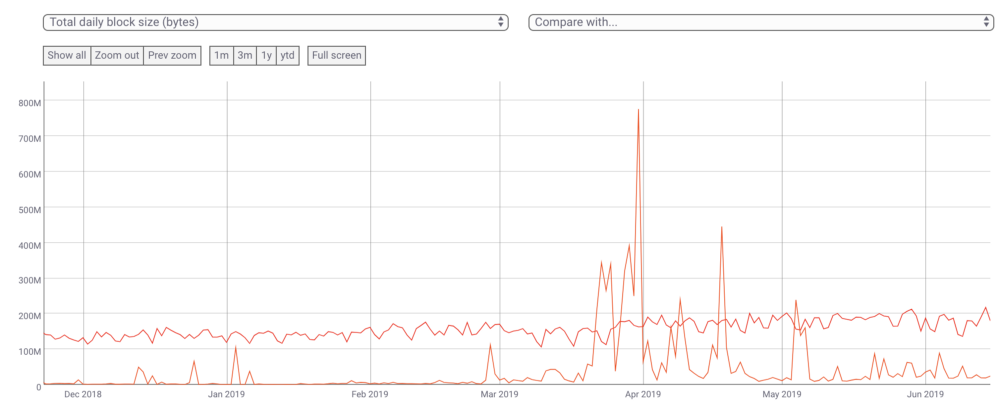

In chains which commit to completely opening up block space like BSV, you end up with a baseline level of low usage (BSV averages <10k daily active addresses, compared to Bitcoin’s 800k+) and occasional inorganic spikes as the chain is injected with data, making validation very difficult in the long term.

Bytes transmitted on chain per day in Bitcoin (red) vs BSV (orange). Coinmetrics

Bytes transmitted on chain per day in Bitcoin (red) vs BSV (orange). Coinmetrics

The case of EOS is an interesting one. Given that block space was made fairly cheap (even though it is technically ‘priced’ with an elaborate system of network resources), EOS had a lot of uneconomical, or spam usage. This is partly because the incentives to create the illusion of activity on chain were high, and the cost to do so was minimal.

So you had millions and millions of ledger entries created through the weight of economic incentives (to promote the chain or certain dApps), burdening the chain with borderline spam. This has had very real consequences. In EOS today, for instance, it is a badly-kept secret that running a full archive node (a node which retains historical snapshots of state) is virtually impossible. These are only strictly necessary for data providers who want to query the chain, but this is an example of a situation where maintaining the canonical history of the ledger becomes prohibitively difficult through a poor stewardship of network resources.

Lastly, the block space debate comes down to a question of sustainability. For a blockchain to be able to charge fees, users must value the block space. However, if block size is completely unbounded, it stands to reason that block space will be worthless. How much would you pay for a commodity that is infinite in supply? By capping block space, Bitcoin is able to sustain a market for ledger entries which will one day replace the subsidy to miners provided by issuance. Opponents contest that increasing the block size allows for more and more usage, which will eventually manifest itself in fees.

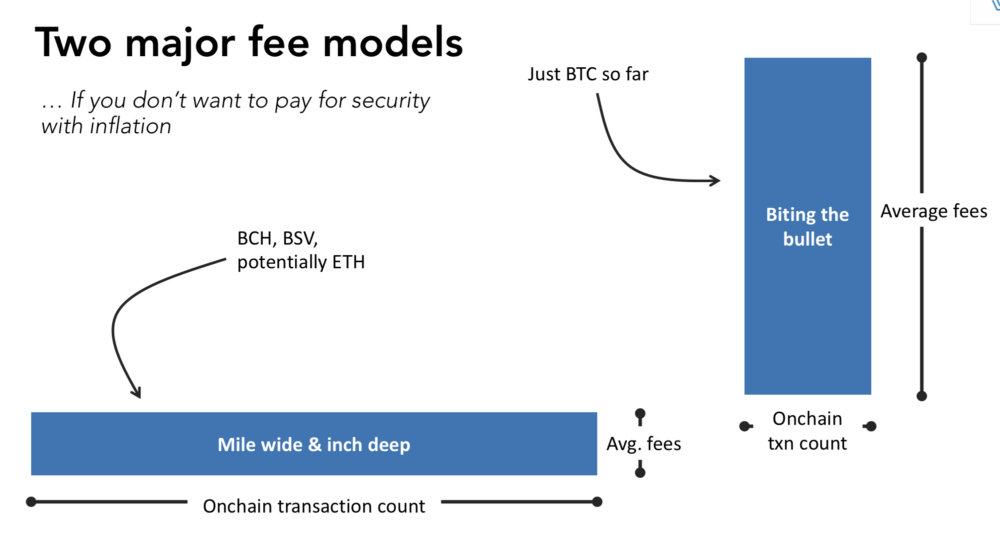

Slide from my talk at the MIT Bitcoin Expo: video here

I call this the ‘mile wide and inch deep’ model of the fee market. Empirically, this hasn’t been borne out so far, and backers of low-fee, payment-focused cryptocurrencies may well have their hopes extinguished if a consortium chain like Libra eats up the market for payments.

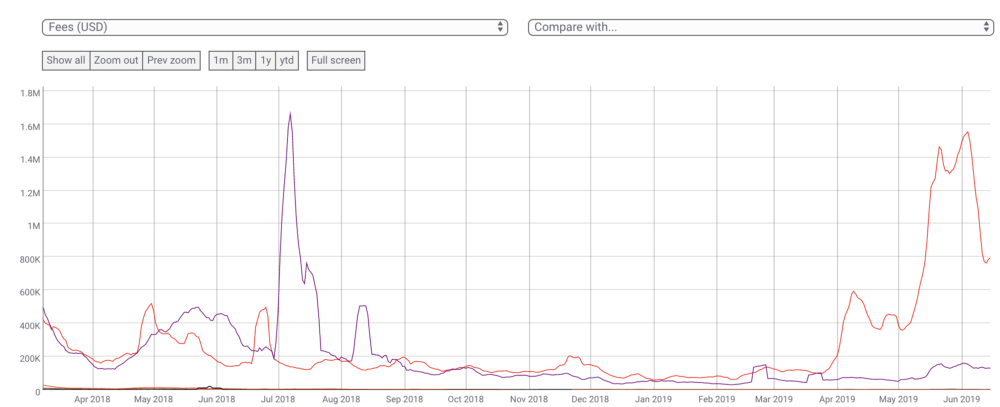

Daily fees (USD) paid to miners for a variety of top blockchains. Coinmetrics

Aside from Bitcoin and Ethereum, no asset even registers on the chart. Only Litecoin can muster over $1k per day in fees. BCH, BSV, Dash, Zcash, Monero, Stellar, Ripple, and Doge are all in the hundreds of $ /day range (chart). This does not bode well for the sustainability of coins which plan to reduce their issuance on a schedule like Bitcoin’s. Currently, no chains aside from Bitcoin and Ethereum appear equipped to enter a regime where fees provide the majority of validator revenue. So pricing block space and allowing a market to develop, although painful in terms of fees, is a critical feature of Bitcoin.

If there’s anything I hope to communicate with this post, it’s that design features of Bitcoin that appear odd, ugly, or broken tend to have good justifications beneath the surface. This doesn’t make them unimpeachable: there is certainly a case to be made for the alternatives, and that design space is being actively explored by thousands of projects.

Satoshi was not an all-seeing savant, and s/he certainly failed to anticipate some of the ways the system would develop, but the tradeoffs that ended up in Bitcoin are generally quite defensible. Whether they are absolutely correct remains to be seen. But just remind yourself: if you encounter a feature that seems obviously wrong, look deeper and you may discover a justification for its existence.

Thank you to Allen Farrington and Matt Walsh for the feedback.