A Guide To Bitcoin’s Technical Brilliance (For Non-Programmers)

A Guide To Bitcoin’s Technical Brilliance (For Non-Programmers)

By Lucas Nuzzi

April 15, 2018

18 minutes is all that it takes to understand Bitcoin better than most people.

In 18 minutes, you will have a good understanding of how hash functions, Public Key Cryptography and Merkle Trees are brilliantly used in Bitcoin.

The purpose of this post is to provide a semi-technical guide to key aspects of Bitcoin’s technology. Over the years, I have found that the best way of achieving that is to dissect everything that happens under the hood when two entities transact.

Of course, I’m talking about Alice and Bob.

But bear with me. It gets dark.

Alice happens to live in country that is going through a massive economic downfall, widely regarded now as a humanitarian disaster. A country where hyperinflation, hunger, unemployment, and violent crime have prevented its citizens from the most basic human rights.

Despite economic calamity, life goes on, and people still need to purchase goods and services on a daily basis. Alice desperately needs to fix the roof of her house, which has partially collapsed. But fixing a roof takes longer than a day, and pricing this service using a hyper-inflated national currency is nearly impossible.

Historically, when a country’s national currency collapses, citizens tend to adopt stable foreign currencies in order to hedge against inflation. Many South American countries that went through periods of hyperinflation informally adopted the US dollar when trying to price services.

But Alice is having problems finding physical US dollar bills. The ongoing crisis, which has now reached its third year, has put a premium on foreign currencies. In order to hedge against hyperinflation, she proposes to pay Roberto (Bob), the roofer, in Bitcoin, which is surprisingly less volatile than her own country’s currency.

Bob requires 0.01 BTC to begin the repairs, but he does not have a bitcoin wallet. In addition to sending him the funds, Alice will also teach Bob how to create a wallet and use Bitcoin.

1) Alice wants to send 0.01 BTC to Bob (I will use quotations to note all the steps in this transaction’s life-cycle)

To transact in the Bitcoin Network, every participant is required to download a specific software to interact with other network participants. This is what’s referred to as a client, which sends requests for specific data to a server. Web browsers, for example, are a type of client that request and interpret data from a server. When a URL is accessed, the browser client sends a request to the server storing the website’s content and, once served the data, it displays that content to the user.

Bitcoin clients work similarly, but there is a key difference. Instead of accessing data from a centralized server, the Bitcoin client interacts with other members of the network to source and validate the integrity of the data, which can easily be determined since every participant of this network is essentially storing the same database. This is a key aspect of the Bitcoin Network, as its decentralization grants unique security properties to the integrity of the data that is exchanged between network participants, or nodes.

Nodes, by definition, are the individual participants of a network. When we refer to the nodes of the Bitcoin Network, we are talking about the people that have downloaded and that are running a Bitcoin client. Collectively, Bitcoin nodes are essentially what the network is made of; a group of interconnected machines running a client and exchanging data.

Nodes may interact with the network by running two types of client; a full client or a light client. Let’s first look at the differences between them:

FULL CLIENTS (ALSO CALLED FULL NODES, OR “THICK” CLIENTS)

As many of us know, a blockchain is simply a structure that can be used to store data. In Bitcoin, transactions are added to block(a group) every 10 minutes, and then chained(connected) to the previous block. The purpose of this data structure is to determine a single, immutable, truth of what happened and when it happened.

Full clients, also called full nodes, store a complete copy of the blockchain in their computers which consists of all blocks with all transactions that have ever occurred in the network; from the very first transaction in the Genesis Block, the first block to ever be mined, all the way to the most recent block the software is able to find. Full nodes are the backbone of the Bitcoin Network, and enforce the rules set forth by the software. These rules guarantee the security, formatting and consistency of all data that is stored on the blockchain, as well as the process by which new data is amended to the ledger.

Since full nodes store a copy of all transactions that have occurred in the network, they are able verify the validity of transactions initiated by any other user. To do that, the software looks at all past transactions that a user has engaged in, thereby preventing malicious actors from sending more than what they possess. Because this is digital money, the only way of preventing a bitcoin from being used twice (Ctl+C, Ctl+V) is to be hyperaware of all transactions that have ever happened.

Downloading an entire copy of the blockchain from other nodes may take some time as the size of the Bitcoin blockchain is currently 164GB. However, this process only needs to be done once. Upon downloading the chain, users only need to download a new block every 10 minutes. All of this is done in the background, automatically, by the client.

LIGHT CLIENTS (ALSO CALLED “THIN” CLIENTS)

Since running a full node has several requirements, such as having sufficient storage space and memory, light clients were designed to ease the interactions with the network and reduce the frictions of owning and using bitcoin. Light clients can, for example, run on a smartphone. Instead of storing a complete copy of the blockchain, light clients only store the header of each block, which is basically a summary of all transactions contained in it.

Only storing the block header requires less disk space, but it limits what light clients can do. A light client is not able to entirely verify the validity of a transaction, but it can confirm by looking at the header if a transaction was included in a block. Its main purpose is to broadcast transactions to the network. Full nodes then receive transactions from light clients, verify them, and add them to a separate bucket with all other unprocessed transactions. Full nodes are only allowed to add these unprocessed transactions to their blockchain when the miners tell them to so. More on that later.

2) Alice helps Bob download a Bitcoin light client, which will enable him to quickly create an account and receive funds.

MULTIPLE CLIENTS AND SERVICE UPTIME

Today, there are dozens of different Bitcoin clients available for download. This diversity is highly desirable, since it diminishes the risk that a bug in a single client will disrupt the entire network. If one client fails, as it has happened in the past, users can download other brands and transact.

This is the reason why Bitcoin has been functional for 99.99% of the time. Not many internet services have comparable uptime, which is in itself remarkable for a 9-year-old open-source project that was launched by an obscure figure.

WALLETS

Although both full node clients and light clients can serve as a user’s wallet, the definition of a Bitcoin wallet is not the same as a client. Technically, a wallet is the collection of data required to send and receive bitcoin. This data includes a public address and a private password.

BITCOIN IDENTITIES & KEYS

Since Bitcoin was built for peer-to-peer payments, all users of the network need a public identity that enables them to identify the parties of every transaction. Like a bank account, this address needs to be unique and users must be able to share it publicly. Conversely, users also need to be able to authorize transactions with a unique private identifier that proves the ownership of funds.

Bitcoin archives that through three unique identifiers:

1) PRIVATE KEY

The Private Key is a completely random combination of numbers and letters that can be used to spend the bitcoin associated with a specific Address. Private Keys, like the PIN number of a checking account, are used to authorize transactions. Below is an example of what a Private Key looks like.

cxprv9xg3pXGrrmSQNqRCZRFmphUZpkzt8s43ESotbcPXk5fLXt6NT3fh2tTPyQ7tW2SWAS9uWjhDJzzex9m8qmAHsJvTN1hctsgiYFK9Moo9Nx1

As you can see, it would be extremely difficult for a human to memorize a Private Key. I don’t even recommend writing it down because you will lose your funds foreverif you happen to miss a character. For this reason, you can represent the Private Key’s blob in a human-readable format using something called a mnemonic key. Believe it or not, the twelve-word mnemonic key below represents the Private Key above.

faith joke visa range turkey expose they bacon gentle hill cushion recipe

Much easier to remember, right? This is one of the most under-appreciated aspects of Bitcoin. For the first time in human history, you can store your wealth in your brain without a third party.

This means that, if the situation in Alice’s country turns into a Civil War, she can flee the country and transfer her wealth by only remembering twelve words. These twelve words can later be loaded into any Bitcoin wallet.

2) PUBLIC KEY

The Public Key is derived from the Private Key using fancy algebra, and acts as an intermediary between a user’s private and public identities. Below is an example of what a Public Key looks like.

xpub6E9pP9ny45P14SNMCzCBFCPwr2QHgWQqZggJg6sMjnGgPo8Hf9tzPwtzHYeKXn6GdACpoKRcvkb2w6pvcAj6kwdw5mKLyDErWXKX8Bhozed

3) ADDRESSES

Addresses are derived from the Public Key using a hash function. I will provide more details on hash functions in later sections, but for now it is important to note that Public Keys and Addresses are not the same.

I often get asked “what is the point of the Public Key if users transact using addresses?” There are a couple of technical reasons behind this intermediation, but it all comes down to privacy and efficiency. Users derive their addresses from their Public Keys, which makes it difficult for someone to pin point a single identity in the network.

Below is an example of what an address looks like. As you can see, the hash of the public key is smaller than the public key itself, which saves space on the chain.

1LGpghBaX7AGbxA5dvpVwR7vMy53R8HcXX

EASY TO VERIFY, PRATICALY IMPOSSIBLE TO REVERT

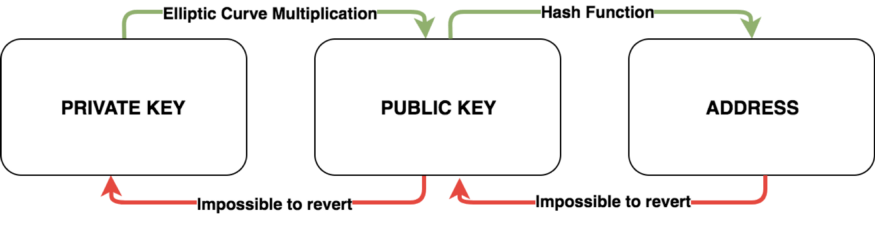

As you can see in the Figure 1 below, there is a mathematical relationship between Private Keys, Public Keys and Addresses. This is achieved by using a principle called a Mathematical Trap Door; a one-way mathematical function that can easily be performed in one direction (i.e. deriving Public Keys from Private Keys), but nearly impossible to be performed in the opposite direction (i.e. deriving Private Keys from Public Keys).

Fig 1. The Relationship of Private Keys, Public Keys and Addresses (Source: Digital Asset Research)

Fig 1. The Relationship of Private Keys, Public Keys and Addresses (Source: Digital Asset Research)

Even though the math behind these operations is mind-blowing (in a good way), I will save its details for more a technical post on Elliptic Curve Cryptography and other technologies being currently researched. For now, keep in mind that, when Alice signs a transaction, she is essentially using her Private Key to create a signature. Through this signature, everyone can easily verify that Alice has a Private Key associated with an address without knowing what the Private Key actually is.

Fun estimates that I have to share:

Q: how many bitcoin addresses can users generate?

A: 1,461,501,637,330,902,918,203,684,832,716,283,019,655,932,542,976

Q: how many grains of sand are there on earth?

A: 9,223,372,036,854,775,807

Have I mentioned that it would take the amount of energy in the entire sun to brute force a Private Key from a Public Key?

Math is magical.

4) Bob has created a wallet through his light client and sends Alice his Bitcoin address over email.

THE TRANSACTION

Simply put, a bitcoin transaction is a signed message that authorizes the transfer of funds from one account to another. Each transaction includes the sender’s address, the receiver’s address, and a signature generated using the sender’s Private Key.

The Bitcoin blockchain has a native multiple-entry accounting system and each transaction has inputs (where the balance came from) and outputs (where it is going to), much like a system of debits and credits. A user’s balance is basically the sum of all debits associated with the Addresses derived from his or her Public Key minus all credits that have been sent to other addresses. A balance is considered spent once it’s used in a transaction.

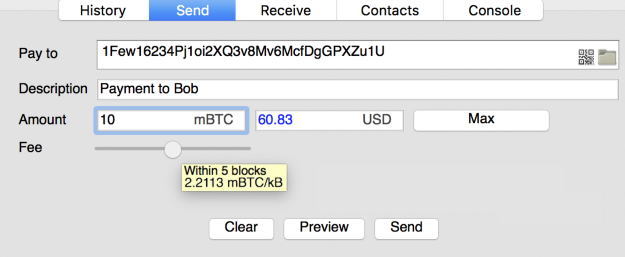

5) Alice now has Bob’s address (1Few1623…), which is the only thing she needs to initiate a transaction.

Fig. 2. Initiating a BTC Transaction using Electrum (Source: Digital Asset Research)

Fig. 2. Initiating a BTC Transaction using Electrum (Source: Digital Asset Research)

When Alice initiates a transaction of 0.01 BTC, or 10 millibits (mBTC), to Bob, her Bitcoin client will look at all previous unspent outputs (debits) associated with her Public Key, and display her total balance. Alice then scans or copies Bob’s address, adds the transaction amount and chooses how fast she wants the funds to reach Bob. The speed at which Bob will receive Alice’s transaction is dependent upon how much network fees Alice is willing to pay.

6) Alice decides how much she will pay in fees, which is proportionate to the speed at which Bob will receive the funds.

Bitcoin relies on certain network participants to group unprocessed transactions into a block and add that block to the ledger, an activity called mining. Miners receive all transaction fees in a block and, therefore, have an economic incentive to prioritize transactions with higher fees. If Alice wants Bob to receive the funds in less than one hour, she will have to pay the miners higher fees.

Since Bob won’t need the funds immediately, Alice decides to pay a rate of 2.21 mBTC per kilobyte in transaction fees, which is enough to make sure Bob receives her transaction within the next 50 minutes, or 5 blocks. Alice previews the transaction to see how much she will pay in fees.

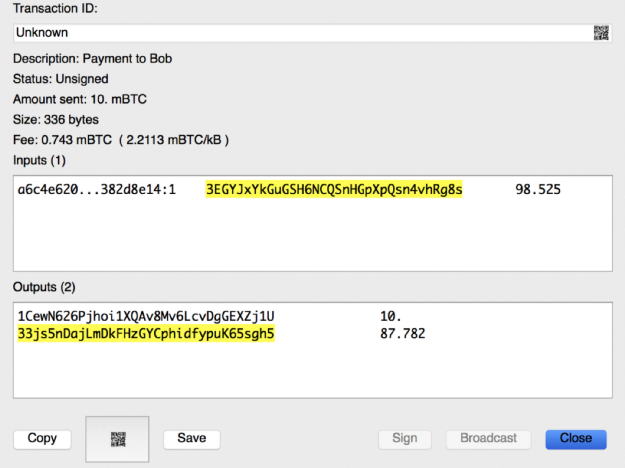

Previewing a BTC Transaction using Electrum (Source: Digital Asset Research)

Previewing a BTC Transaction using Electrum (Source: Digital Asset Research)

At a transaction fee rate of 2.21 mBTC per kilobyte, and the size of her transaction being 336 bytes, the total amount paid in network fees is 0.743 mBTC, or $4.65 USD (2.21 * 336).

Note: the screenshot on the left was taken when Bitcoin transactions were at an all-time-high. A similar transaction today would cost less than a dollar.

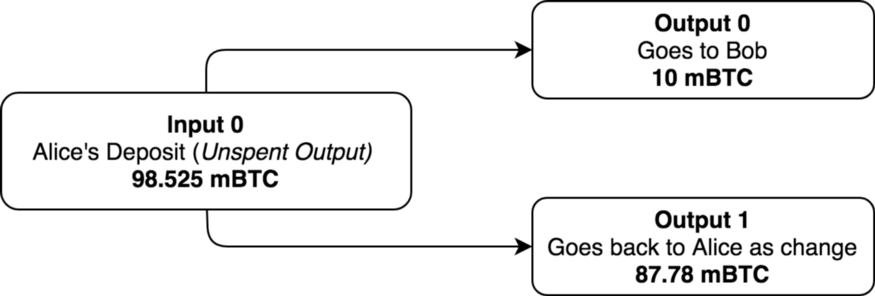

In essence, a Bitcoin transaction is the exchange of ledger entries, which are represented as inputs and outputs. The specific transaction initiated by Alice contains only one input and two outputs. To send 10 mBTC to Bob, Alice’s client uses a past transaction as an input to prove that she has a balance higher than the amount being sent. A day earlier, Alice deposited 98.525 mBTC to the address she will use to send the funds to Bob. Her client will use this transaction as an input since its value is higher than the amount she will send to Bob. Her client will also send the difference between yesterday’s deposit and 10 mBTC (in other words, the change) back to Alice.

Two outputs are created; the first output of 10 mBTC goes to Bob, as it represents what Alice is sending, and the second output of 87.78 mBTC goes back to Alice’s address as change. Notice that the 87.78 mBTC output that Alice will receive as change is already accounting for the 0.74 mBTC that she will pay in network fees.

The Inputs And Outputs Of Alice’s Transaction (Source: Digital Asset Research)

The Inputs And Outputs Of Alice’s Transaction (Source: Digital Asset Research)

At times, inputs and outputs can be confusing. That’s because the output of a previous transaction becomes the input of a new one. In the example above, Input 0 is the output of the deposit made a day earlier. Because that output has not been used in any other transaction (i.e. it’s an u nspent output), it can be used as input for a new transaction. Once used, it becomes a spent output that can’t be noted as an input for a future transaction.

Before this particular transaction can be broadcasted to the network, Alice needs to prove that she possesses the Private Key associated with this address by signing the transaction. Alice can sign transactions by loading the text file used to store it, or manually entering her 12-word mnemonic key. Alice’s client will then combine all details from the transaction and convert it to hexadecimal format.

After the conversion, Alice’s entire transaction looks like this:

0100000001148e2d38c3689aad33912d200466fae64f5838f78b3b9f86b01c248720e6c4a601000000fdfe0000483045022100c30774a82e9073eddb6087f41a59072d29eaee7c3d1421d6f87176ebdff4d7d0022062de162d52c6b547fa24691df56c9da4d6eb7ee73af414af4b60ccce9e69e9e601483045022100f3e2f4a4b970c266a6bd8673cc4ebceea552d8f95a08a35f9961b4d82dfbb8b1022006bd96c993d8b3abb5f709575a0bd4aaa3dfc7ef4be2332e5742dea07d0cc3a9014c69522102645819411857186df087f733675574e37372b4de78471b5c87b832d977f3007e21034df63462f237819e46a9aa586a87597fde69df7ed2b5b583de38ae0d4abc183a2103ec10bb20748527001b900474f72440e1a9591305b991f79cbf0897413ec0cfb753aeffffffff0240420f00000000001976a9147fd627956048ff5b5cff26183df231540c637d2e88acd8f185000000000017a914167a1e9c105bd7bc1a5e86d3d576078a63f0472c8700000000

The above string is what’s shared with other members of the network. Once broadcasted, the nodes around Alice verify the transaction’s validity and disseminate it to other nodes until the transaction gets processed by the miners. As mentioned earlier, every node stores a bucket of unprocessed transactions. This is what’s called the memory pool, or mempool. When the mempool is full and nodes in the network are storing a large number of unprocessed transactions, the network fee rate per kilobyte increases, since memory is scarce. As result, network mining fees also increase.

Accordingly, the Bitcoin mempool is used as a proxy for network congestion and transaction costs, since a high number of unprocessed transactions = less space in the mempool = higher fees.

I must emphasize that bitcoin network fees are priced only on the basis of transaction size (kilobytes), regardless of the amount being sent.

THE VERIFICATION OF BLOCKS THROUGH MINING

The term mining gained popularity because it described a parallel with a real-world activity that is probabilistic in nature, and that gives no guarantees of success.

Gold miners know that, even if they spend significant amounts of resources in the process, there is no guarantee that a precious metal will be found. Although this can be a useful analogy to describe the probabilistic nature of the activity, the term mining does nothing to help understand the process itself, which is one Bitcoin’s greatest accomplishments (so far) when it comes to both user adoption and network security.

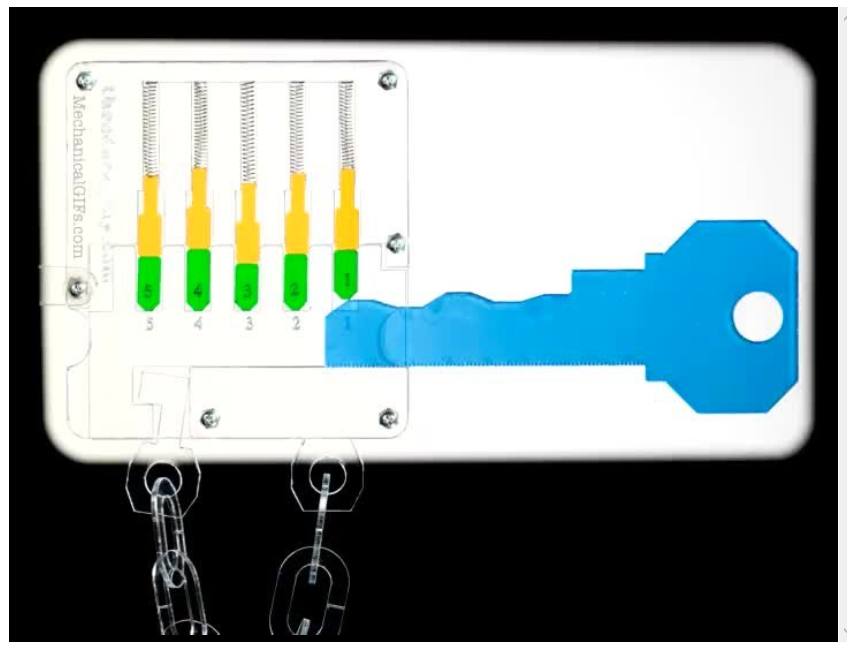

The actual activity miners perform is more analogous to the job of a real-world locksmith than that of a real-world miner.

Imagine that, every ten minutes, the Bitcoin protocol gives the locksmiths in its network a closed lock with an unknown key. Only if one of them is able to open the lock and attach a new group of transactions to the chain, a reward is issued. To find the key, the successful locksmith must try millions of different combinations, which takes both time and effort. The locksmith must prove to the competing locksmiths that he went through the hassle of trying different combinations by showing them the real key, which they can then replicate and verify for themselves. Producing the key, which is the proof that work has been done, automatically grants the successful locksmith a reward that is, in practice, proportional to his efforts.

Proof-of-Work, get it?!?

Once a locksmith finds that the coordinates 5–4–3–2–1 opens the lock, this combination becomes the Proof-of-Work. (Source: mechanicalgifs.com)

Once a locksmith finds that the coordinates 5–4–3–2–1 opens the lock, this combination becomes the Proof-of-Work. (Source: mechanicalgifs.com)

The protocol is always aware of how many locksmiths are trying to find the key coordinates to its lock so that it takes, on average, ten minutes until a locksmith can find a correct key that opens the lock. If there are only a dozen locksmiths in the network, the lock will be small and can easily be opened using a short key with very few grooves. Conversely, if there are hundreds of locksmiths competing in this challenge, the protocol will give them a large lock that requires a long key with many grooves. With regards to Bitcoin, millions of different combinations need to be tested before the correct key is found.

Consider that when Bitcoin launched, only a simple metal file was required to produce a valid key. Now, this activity can only be done with an ASIC, a piece of hardware that is optimized to compute a specific algorithm. The rise of Bitcoin ASICs is analogous to selling these locksmiths electric metal grinders that exponentially increase their abilities to test different key combinations. As the economic incentives of this activity increased in value, the lock increased in size.

This illustrative Bitcoin lock is now massive, which greatly contributes to the security of the network. Given the competitive and probabilistic nature of the activity itself, it is unlikely that the same locksmith will find the key for consecutive locks over a period of time. Unpredictability is an important feature because it diminishes the likelihood that a malicious actor will double spend funds by mining consecutive blocks. However, the increase in difficulty, when coupled with specialized hardware, creates barriers of entry for the average user, which ultimately translates into some centralization.

Prominent members of the community are now discussing whether to embrace or scrutinize the use of ASICs. As I stated in this article, I see the confluence of ASIC manufacturer + miner as potentially dangerous. The caveat is it does increase network network security by orders of magnitude (at the expense of decentralization, of course).

PROOF-OF-WORK AND HASH FUNCTIONS

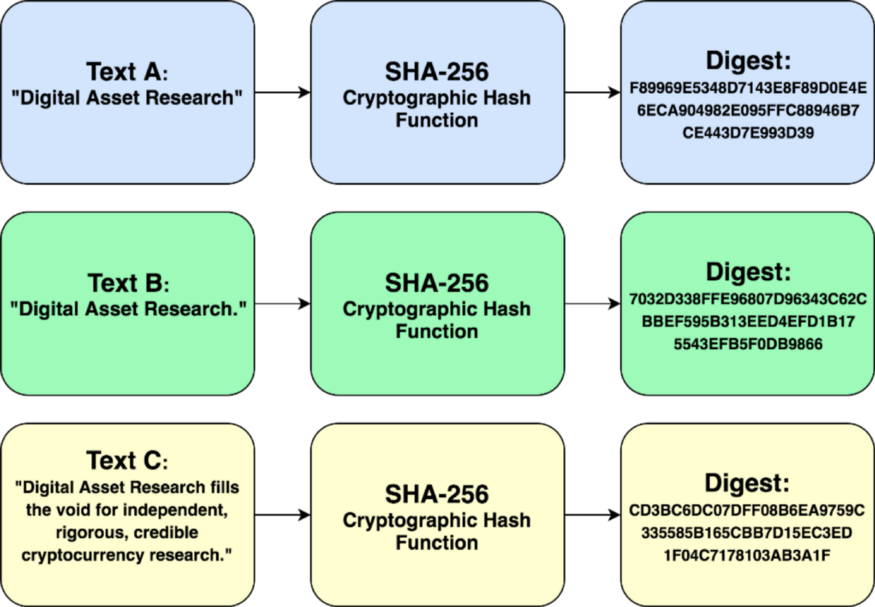

As you may know, the mathematical puzzle referred above is based on a cryptographic hash function. Generally speaking, hash functions map every piece of data in a file, assign identifiers to it, and produce an output of fixed length. In other words, hash functions are used to compress data of any size to a standard output, and that output is called the hash. You can put the entire Library of Congress through a hash function and compare the output with the hash of the word it; both outputs will have the same size.

To produce proof-of-work, Bitcoin miners use SHA-256; a hash function originally designed by the NSA for the compression of sensitive information. Before being able to add a block to the blockchain, miners must use the SHA-256 function to combine the data inside the block with a specific, unknown, number. This number is called the nonce. Miners need to find a nonce that, when combined with the data within a block, produces a hash that starts with the target number of leading zeroes.

Hash functions, as shown in Figure 5, are highly sensitive to the slightest change. Therefore, miners must try millions of different nonces within that 10-minute period in order to find a nonce that, when combined with a block, begins with the target number of zeroes. If you read the previous section carefully, you will realize that nonce is the key the locksmiths are competing to find.

Fig. 5. Example of a Hash Function (Source: Digital Asset Research)

Fig. 5. Example of a Hash Function (Source: Digital Asset Research)

Changing a transaction that has already been added to a block requires changing the entire block. Bitcoin works because the data structure of its blockchain makes it immutable; once a block has been mined, nothing in it can be changed without affecting the entire block.

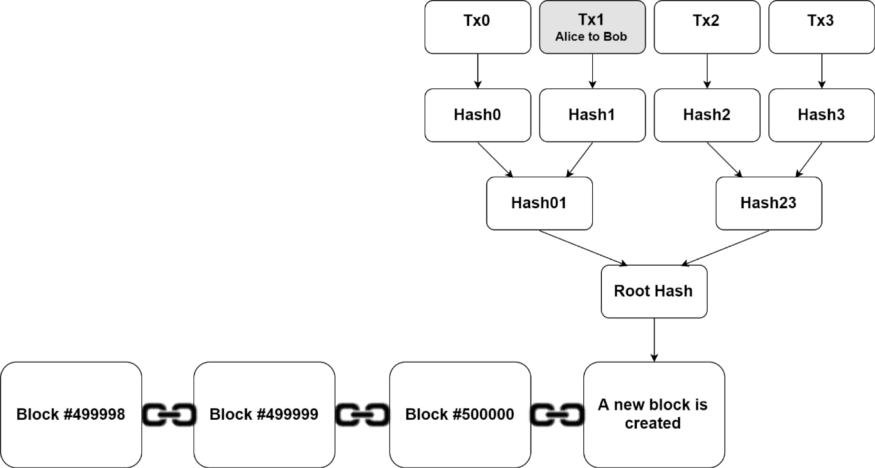

This is achieved using a data structure called a Merkle Tree,which basically combines every piece of data within a block so that all data is interdependent. As you can see in Figure 6, Alice’s transaction to Bob (Tx1) is hashed to produce Hash1, which is then hashed with Hash0 (the hash of another transaction that happened at the same time) to produce Hash01. The protocol does that to every single unconfirmed transaction that will be added to the block until a root hash is found.

Fig. 6. Example of a Merkle Tree Structure (Source: Digital Asset Research)

Fig. 6. Example of a Merkle Tree Structure (Source: Digital Asset Research)

The root hash is the hash of all transactions within a block. If the slightest bit of data within any of these transactions is changed, the root hash will be completely different. This is the reason why the term blockchain has been highly popularized; the immutability of this data structure is highly desirable for many different applications.

The block header referred in the section on light clients is the combination of the root hash with the block header of the previous block in the chain. This is what essentially links blocks together in a blockchain. The block header also includes other data pieces such as the nonce, the current time and how difficult it was to mine it.

7) Finally, Alice’s transaction is added to a block along with many other transactions. Once the block gets mined, Bob can download it and verify that the transaction has been confirmed.

INCENTIVE STRUCTURE AND BLOCK REWARDS

The Bitcoin protocol has a native incentive mechanism that rewards miners that are able to produce valid Proof-of-Work. This amount is divided by half every 4 years. At the time of writing, it is 12.5 BTC per block. As stated earlier, miners also receive network transaction fees from every transaction they choose to include in a block.

When the Bitcoin Network launched in January 2009, block rewards were 50 BTC per block. As expected, block rewards halved to 25 BTC in November 2012, and to 12.5 BTC in July 2016. In the year 2140, the Bitcoin protocol will stop generating new coins and mining rewards will only be based on network fees. At that point, around 21 million bitcoins will be in circulation.

Bitcoin’s brilliant incentive layer has greatly contributed it its adoption since it provides a unique economic structure based on scarcity. Incentives are defined by an algorithm, which allows Bitcoin’s inflation to be precisely modeled. This makes Bitcoin a good candidate for the coin of the future, since its monetary policy is determined by math in the form of software.

FINAL REMARKS

The first time I played around with Bitcoin’s codebase was in the Fall of 2012, when I was still in college. I remember being dismissive of it at first, which I now understand was because of ignorance. Bitcoin’s simplicity can be very deceiving, and it is easy to overlook its elegance.

Ignorance is the real reason why Bitcoin has been declared dead so many times. This shouldn’t come out as a surprise, after all, understanding this mix of Cryptography, Computer Science and Economics requires both time and effort.

But once you get it, its technical brilliance is undeniable.

I want to send a huge thanks to Andreas M. Antonopoulos for writing “Mastering Bitcoin.” It opened my mind to so many under-appreciated aspects of the Bitcoin protocol. If you don’t have a technical background, I highly recommend his latest book, The Internet of Money.

If you find this post useful, please share it on social media and join the battle against crypto-ignorance! Help this post gain more visibility on Medium by clicking the clap button as much as possible. If you are interested in the space, you should also sign up for DAR’s free daily newsletter. It’s a great way of keeping up with what’s happening in cryptoland, and you will be notified when we post things this.