The Flase Dichotomy of Utility and Store of Value

The False Dichotomy of Utility and Store of Value

By Qiao Wang

Posted July 5, 2018

There seems to be a growing belief that a cryptoasset doesn’t need to have high utility to be a good store of value (SoV), and conversely, it doesn’t need to be a good SoV to have high utility.

A more radical version of this even says that a good SoV cannot have high utility, and a high-utility asset cannot be a good SoV.

This leads to a popular, binary classification of tokens as being either a SoV or a utility token. For instance, people tend to classify Bitcoin as a SoV, and Ethereum as a utility token.

Origin of the Dichotomy

I suspect that the “SoV vs. utility” mental model stems from the realization that blockchains are characterized by two technical tradeoffs at the base layer:

- Decentralization vs. scalability: if you need to process a lot of transactions at the base layer, you may have to sacrifice decentralization, for instance by increasing the block size or by reducing the number of validators.

- Security vs. featurefulness: if you want the base layer to be featureful, for instance by introducing Turing-completeness, you may enlarge the attack surface.

Decentralization and security are important qualities of a SoV, while scalability and featurefulness create utility potential. Hence, SoV and utility are believed to be at odds with each other.

The velocity thesis, as reasoned from the equation of exchange M = T/V, further strengthens this view. As velocity (V) is inversely related to monetary base (M) in the equation, it is posited that utility tokens are unlikely to accrue value because users are unwilling to hold the asset.

Complementary network effect

Solutions to the aforementioned technical tradeoffs are beyond the scope of this discussion. However, we shall argue, from an economic point of view, that utility and SoV are not only a false dichotomy, but also form a synergistic relationship with each other, by exhibiting what we call a complementary network effect.

Complementary network effect refers to situations where increase in usage and value of one product increases usage and value of a separate product, which in turn increases usage and value of the original product.

For instance, an increase in the number of useful iOS apps make iOS devices more valuable, which in turn leads to more development of apps on iOS. An increase in the variety of available DVDs make DVD players more valuable, which in turn leads to more DVD production.

In the case of cryptoassets, we can view utility and SoV as two separate products of the same network. All else equal, more utility makes a cryptoasset a better SoV, which in turn increases utility.

This is not to say, for instance, that high utility will lead to a good SoV in the absolute sense. Rather, higher utility will lead to a better SoV in the relative sense. For instance, if an asset has a high inflation rate or low censorship resistance, utility not be sufficient to make it a good SoV, but will help it better store value than otherwise.

SoV as a complement to utility

Let’s first look at why SoV leads to better utility. To understand the symbiotic relationship between the two, we must first understand what they really are:

- An utility asset is one that we exchange for another product or service.

- A SoV asset is one that we hold so that at some point in the future we exchange it for another product or service.

The key insight here is that utility involves exchange, and an exchange involves both a buyer and a seller. If you are a buyer, you may not care about whether the utility asset you are giving up is a good SoV. In fact, if you had a choice between spending a good SoV and a bad SoV, you’d probably want to spend the bad one. But the seller, who is your counterparty, prefers to accept a good SoV, because obviously they are the one who will hold the asset.

Some argue that sellers don’t care because if you pay them a bad SoV, they may be able to immediately dump it for a good SoV. But as a matter of fact that additional trade comes with a cost, be it a financial, temporal, or mental, and thus is less preferable.

I have travelled to at least 20 developing countries in Latin America, Eastern Europe, Africa, and Asia, and almost everywhere I go the USD is at least as widely accepted as the local currency. Why is the USD so popular even if it’s not a legal tender? Why do locals prefer it over some other international currencies? Because the Federal Reserve is the most capable central bank in the world at maintaining the value of its currency.

Electoral power

A second-order effect of being a good SoV is that, if a critical mass of people hold the asset in a democratic country, it makes it very hard for the government to ban or otherwise suppress the asset, which clears the path for utility adoption.

In January 2018 South Korean Justice Minister caused an uproar after he called for a ban on cryptocurrency exchange in a press conference, and subsequently softened his stance. Some estimates put cryptocurrency ownership in the country as high as 33 percent of the adult population. Arguably, South Korea has reached the critical mass of electoral power.

Utility as a complement to SoV

Here’s a thought experiment. Suppose that a cryptonetwork is worth $100,000 and there are 10 users. Then on average each user would have to hold $10,000 worth of tokens at any point in time. Maybe that’s too much, and so they would want to dump the tokens. Suppose now that there are 10,000 users in the $100,000 cryptonetwork. Then the average user would only hold $10 worth of tokens, and happily do so for convenience and without worrying too much about the impact of their token holding on their overall portfolio.

This is the intuition behind usage creating value. But there is more to it. An increase in utility actually improves the very properties of a good SoV, such as liquidity, security, decentralization, and intersubjective beli ef.

Liquidity

Utility increases liquidity because people need to trade the asset in order to use it. For instance, imagine that prediction markets and gambling platforms, which are prohibited by many governments around the world, become wildly successful on a censorship-resistant platform like Ethereum. Then people will have to exchange fiat for Ethers in order to use those apps, and then exchange Ethers for fiat to cash out.

Liquidity is especially powerful as it is self-reinforcing. The more liquid an asset has been historically, the more speculators it will attract.

But why is liquidity important for a SoV in the first place? As previously defined, a SoV is an asset that we hold so that at some point in the future we can exchange it for another product or service. If liquidity of the asset is lower, then the cost of exchange is higher, and hence by definition the asset would be a worse SoV.

Security

Miners and stakers need economic incentives to secure the network. They can charge users through transaction fees or holders through inflation. And here’s the elephant in the room. An inflationary monetary policy obviously leads to a worse SoV. So if the network doesn’t want incentives to come from inflation then they must come from transactions, i.e., utility. But if there is no transaction in a deflationary cryptonetwork, who will secure it?

The perfect example of this is Bitcoin, which currently is the best SoV cryptoasset. As its inflation trends to 0, miner rewards will have to come from transaction fees. If they are no longer incentivized to secure the network due to the lack of block rewards and transaction fees, then Bitcoin will obviously lose its SoV status.

Decentralization

The activation of Segwit showed the world that users operating full nodes had tremendous governance power even if the majority of miners wanted a different direction. By extension, it demonstrated that the more utility a network has, the more likely it is to have a diverse set of stakeholders, none of whom can change the rules of the network on a whim.

Would Bitcoin have been equally immune to changes during the first couple of years, when it had many fewer users with skin in the game, and therefore less checks and balances?

How decentralized a cryptonetwork is ultimately boils down to how immune it is to oligarchs attempting to change the rules, or to change states not according to the rules. This is a crucial property of a SoV because a good SoV is one whose monetary policy is credible, transactions cannot be censored, and balances cannot be stolen, by one or few malicious actors.

Intersubjective belief

The familiarity principle is a phenomenon by which mere exposure to a particular thing makes people like it more. An obvious real-world application of this psychological trick is advertising. Another example is that people tend to invest in domestic companies as they are less exposed to international news. If we use Bitcoin as a payment rail or Ethereum as a dapp platform on a day-to-day basis, we could develop a subconscious attachment to them.

I debated internally for a long time whether or not this is relevant to SoVs, as this is getting into the realm of evolutionary psychology or even philosophy. Then I asked myself a few questions.

- Why is gold almost two orders to magnitude more valuable than Bitcoin even if the latter is almost strictly better?

- How did Nixon successfully get the USD off of Bretton Woods?

- Why has ETH been more valuable than ETC ever since the fork even if the latter maintained immutability?

The answer may be intersubjective belief, a term borrowed from Sapiens. “Intersubjective belief is something that exists within the communication network linking the subjective consciousness of many individuals. If a single individual changes his or her beliefs, or even dies, it is of little importance. However, if most individuals in the network die or change their beliefs, the inter-subjective phenomenon will mutate or disappear.”

Religion is a intersubjective belief. Capitalism and democracy are in many ways intersubjective beliefs. Money is also an intersubjective belief.

- The value of gold does not only stem from its durability and scarcity, but also benefits from a strong shared belief that has been built through thousands of years of human exposure.

- America and the world continued to use the USD without much turmoil after it got off gold, as people have been used to transacting reliably using the same pieces of paper during the several decades prior.

- ETH has been more valuable than ETC partly because ETH proponents were more trusted by the community and thus more influential on the intersubjective belief.

Empirical Evidence Against the Velocity Thesis

It’s perfectly fine to reason about the velocity thesis using common sense, for instance, by saying something along the lines of “more people willing to hold the asset reduces circulating supply thereby driving price up”. However, it’s highly handwavy that many proponents of the velocity thesis use the tautological equation of exchange M=T/V to conclude that:

- Utility does not lead to value.

- Value is suppressed by velocity.

This is because the growth of velocity (V) could merely be a consequence of higher utility (T), rather than users’ lower desire to hold the asset which would suppress value (M).

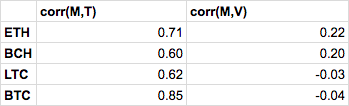

Indeed, empirical evidence (data source: coinmetrics.io) shows that:

- Utility (T) has historically been strongly correlated to value (M).

- Value (M) has historically been uncorrelated, or evenly weakly positively correlated to velocity (V).

One could argue that the velocity thesis does not apply in the early, speculative phase, but will eventually hold at equilibrium. But since the equation of exchange is borrowed from the macroeconomic world of fiat currencies to reason about the microeconomic world of cryptocurrencies, which by the way is completely nonsensical, a natural question one would ask is, does the velocity thesis even hold for fiat currencies?

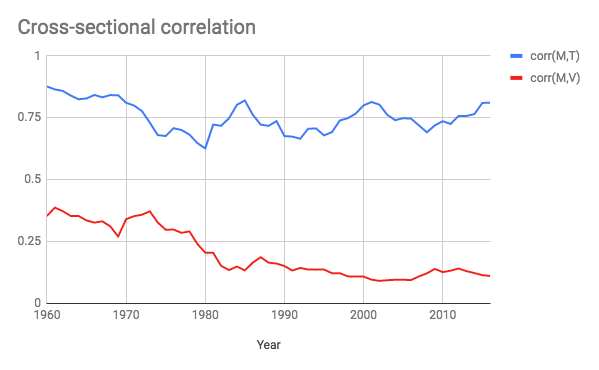

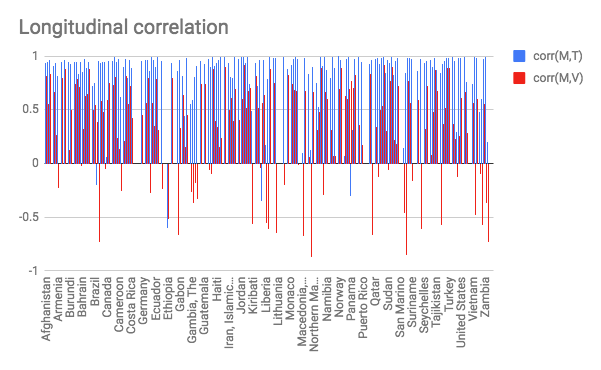

Unsurprisingly, both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (data source: worldbank.org) show that once again:

- Utility (T) is strongly correlated to value (M).

- Value (M) is positively correlated to velocity (V).

In other words, the empirical evidence in both crypto and fiat is:

- Consistent with our reasoning that utility and SoV are synergistic with each other. It does not prove our thesis, but is coherent with the latter.

- Inconsistent with, and therefore rejects, the null hypothesis that velocity diminishes value.

Conclusion

If the technical tradeoffs described earlier can be solved, then there is no reason to believe that SoV and utility cannot make each other better. Thanks to the complementary network effect, SoV properties such as sound monetary policy and security drive more users to transact on the network and developers to make network more usable, which in turn reinforces the SoV status of the cryptoasset.

That’s a big “if”, of course.

However, we should not underestimate the ingenuity of the engineers who are working on these problems. L2 scalability solutions that also preserve L1 decentralization on their way to production. Ethereum had egregious security issues on the application layer, but these issues don’t seem to be unsolvable with better coding practices, and the base layer has been remarkably issue-free so far, in spite that many believed otherwise back in 2014.