Schnorr Signatures & The Inevitability of Privacy in Bitcoin

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

Schnorr Signatures & The Inevitability of Privacy in Bitcoin

By Lucas Nuzzi

Posted March 13, 2019

Schnorr Signatures in the void.

Schnorr Signatures in the void.

Thanks to Pieter Wuille for generously providing feedback on this article and educating me on Schnorr. Since his review, I’ve made lots of changes to simplify key concepts presented here. *Any errors & opinions found herein are my own*

Digital signatures are the backbone of online sovereignty. The advent of Public-key cryptography in 1976 paved the way for the creation of a global medium of communication, the internet, and an entirely new form of money, bitcoin. While the fundamental properties of public key cryptography have not changed much since then, there are now dozens of open-source digital signature schemes available in the cryptographer’s toolbox.

When Satoshi Nakamoto began to work on Bitcoin, one of the key design choices to be considered was which signature scheme to use in this open, permissionless financial system. The requirements were clear; Satoshi needed an algorithm that was widely-used, well-understood, sufficiently secure, lightweight, and, most importantly, open-source. Out of all options available at the time, he went with the one that fit that criteria the most: the Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm, or ECDSA.

Back then, ECDSA was natively supported by OpenSSL, a set of open-source encryption tools developed by cypherpunk veterans to improve the privacy of online communications. Relative to other popular schemes, ECDSA carried the benefits of leaner computational requirements and shorter key lengths; useful attributes for a digital form of money. At the same time, it also provided a proportionate level of security to schemes like RSA: a 256-bit ECDSA key, for example, has equivalent security to a 3,072-bit RSA key, but it is a fraction of its size.

The hard work of Pieter Wuille and others on an improved curve (as in Elliptic Curve) called secp256k1 made Bitcoin’s ECDSA faster and more efficient. However, there are still inherent deficiencies in ECDSA that justify replacing it all along. After a couple of years of research and experimentation, a new signature scheme is set to increase the privacy and efficiency of Bitcoin transactions: the Schnorr Digital Signature Scheme.

In this article, I provide a general overview of the multiple implementations of Schnorr signatures and their corresponding benefits. Then, I explore MuSig, a new multi-signature standard that serves as a building block for novel Bitcoin technologies like Taproot. Lastly, I describe how the fully realized version of Schnorr can break the heuristics used in blockchain analysis and, at the same time, help develop a strong fee market in Bitcoin’s main layer.

THE RISE OF SCHNORR SIGNATURES

Even though the Schnorr digital signature scheme carries many benefits over ECDSA, it is certainly not new. It was invented by Claus-Peter Schnorr, a German cryptographer and academic, while he was a professor and researcher at the University of Frankfurt in the 1980s. His proposed signature scheme was an amalgamation of the research and work of David Chaum, Taher EIgamal, Amos Fiat and Adi Shamir. Nevertheless, before publishing it, Claus Schnorr filed multiple patents for his newly invented scheme, which, for years, prevented its _direct _use.

Interestingly enough, ECDSA’s predecessor, DSA, was a hybrid of the ElGamal and Schnorr schemes that was solely devised to circumvent Claus Schnorr’s patents. In fact, only two months after Schnorr’s U.S. patent was issued, DSA’s progenitor, the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), also filed a patent for its workaround. And here’s a bit of prime cypherpunk history: after that happened, Claus Schnorr became very defensive of his patents, and directly responded to his critics in the Coderpunks mailing list; an offshoot of the original Cypherpunks mailing list. His responses can be read here and here. An internal NIST memo describing _Patent Issues _can also be found here.

In 2008, nearly two decades after the introduction of the Schnorr signature scheme, Claus Schnorr’s patent expired. Coincidentally, 2008 was also the year our favorite cypherpunk, Satoshi Nakamoto, was implementing Bitcoin. Even though Schnorr signatures could have been used at the time, they were not standardized nor widely used, which was probably Satoshi’s motivation to go with ECDSA instead. Although frequently described as _atrocious _by cryptographers and mathematicians alike, ECDSA was (and still is) widely used and it provided safer option for Bitcoin back then.

SCHNORR ON BITCOIN

Fast forward another decade and Schnorr’s scheme is much less esoteric today, with standardized implementations like ed25519 becoming a popular option for some altcoins. Informal talks about potentially implementing Schnorr on Bitcoin date back to this 2014 BitcoinTalk thread, but a proposal was only formalized after years of research and experimentation, when Pieter Wuille wrote the Schnorr BIP. This draft BIP describes the specifications and technicalities of a potential Schnorr implementation, which would carry the following benefits over ECDSA:

· Security proof: The security of Schnorr signatures is easily provable when a sufficiently random hash function (random oracle model) is used and the elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP) used in the signature is sufficiently hard. Such a proof does not exist for ECDSA.

· Non-malleability: ECDSA signatures are inherently malleable, which may enable a third party without access to the private key to alter an existing valid signature and double-spend funds. This issue was formally discussed in BIP62. In comparison, Schnorr signatures are provably non-malleable.

· Linearity: Schnorr signatures have the remarkable property that multiple parties can collaborate to produce a signature that is valid for the sum of their public keys. This is the building block for various higher-level constructions that improve efficiency and privacy, such as multi-signatures and other smart contracts.

The security proofs provided by Schnorr, as well as its non-malleability guarantees, offer clear benefits over ECDSA. A soft-fork could be justified solely on the basis of these two benefits. However, it is Schnorr’s Linearity property that is particularly exciting. In essence, this enables multiple signers in a multi-signature (multisig) transaction to combine their public keys into an aggregated key that represents the group; a property that has been called key aggregation.

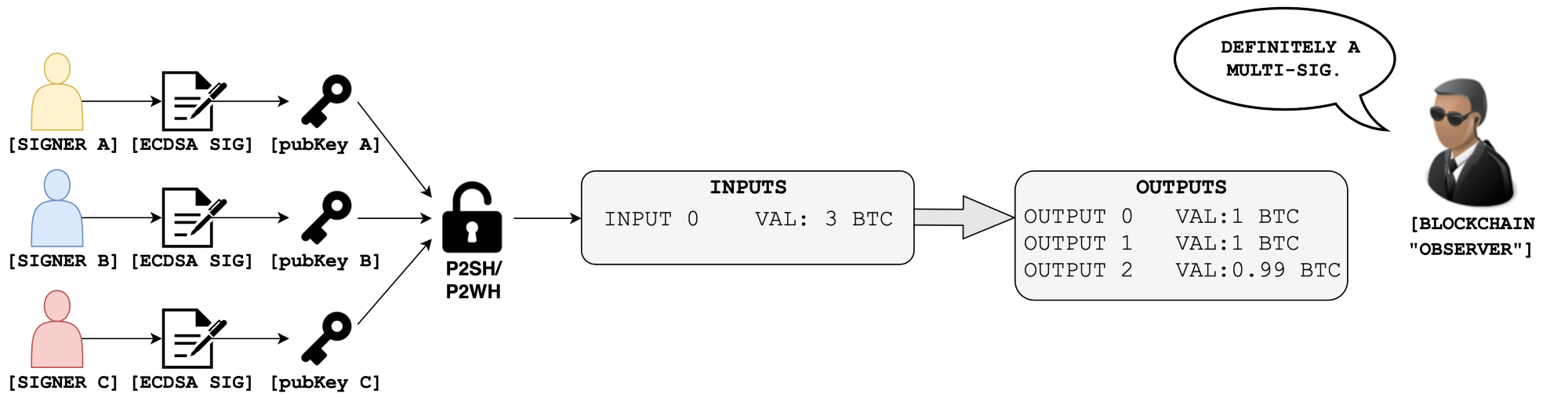

While the ability to fuse keys may sound trivial, the benefits of key aggregation should not be underestimated. Since multisigs are not natively supported by ECDSA, they had to be implemented in Bitcoin via a standardized smart contract (yes, Bitcoin has smart contracts too) called Pay-to-ScriptHash (P2SH). This enables users to add spend conditions called _encumbrances _to specify how funds can be spent e.g. “only unlock balance if both Alice and Bob sign this message.”

The first problem with P2SH is that it requires knowledge of the public keys of all signers participating in the multisig, which is not an efficient system. Aggregating these keys would allow for more efficient validation as only one key needs to be verified by the network, rather than _n _keys. That also means less footprint on the blockchain, lower transaction costs, and improved bandwidth.

The second problem with P2SH is that it offers very little privacy guarantees. As specified by BIP 13, P2SH transactions require different addresses that begin with the number 3. This allows blockchain observers _to not only identify all P2SH transactions in the network, but also pin point the identities _within the multisig:

Not good.

Not good.

In the example above, the network would be aware of (1) the existence of a multisig transaction, (2) how many signers it is comprised of and (3) who the signers are. Not good for operational security, especially for use cases like 2FA. Not good for privacy.

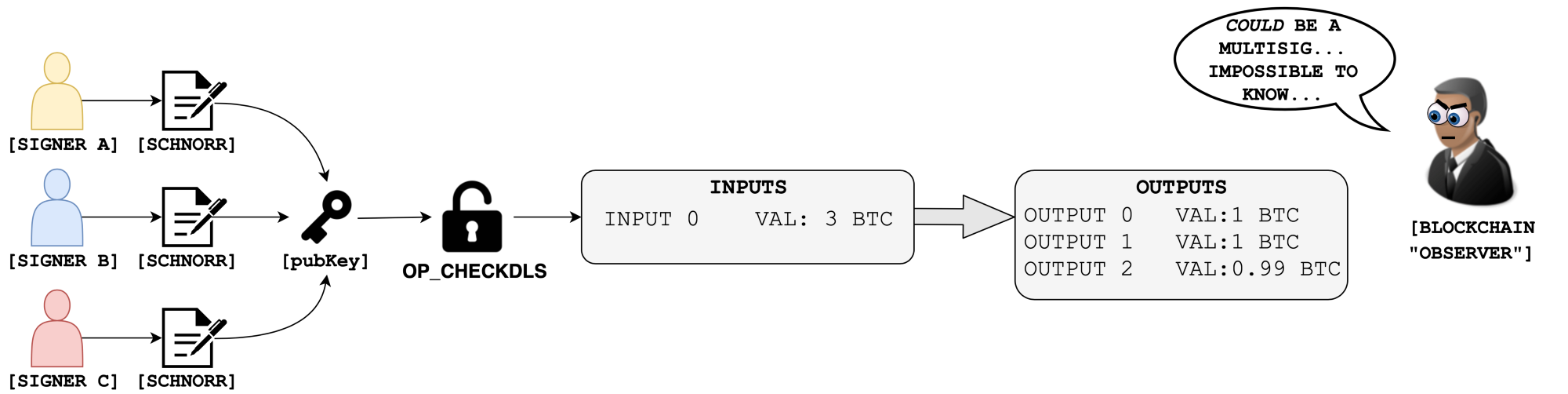

Key aggregation, on the other hand, allows signers to remain anonymous and does not compromise operational security by revealing the keys required to unlock a balance. Most importantly, key aggregation makes it so that multisigs can become indistinguishable from regular transactions:

Good.

Good.

The first iteration of Schnorr in Bitcoin will retire the OP_CHECKSIG and OP_CHECKMULTISIG family of opcodes currently used with ECDSA in favor of a new class that has been called OP_CHECKDLS. Without going into too much detail, DLS stands for Discrete Log Signature and it allows signatures to be verified more efficiently with less opcodes.

Back in early 2018, Gregory Maxwell, Andrew Poelstra, Yannick Seurin, and Pieter Wuille published a white paper on a new Schnorr-based multi-signature scheme called MuSig. Since the publication of MuSig, they have been working hard to translate the proposed multisig scheme into usable code.

One of the most interesting things about MuSig in the context of key aggregation is the possibility for the creation of private smart contracts outside of the blockchain. In essence, MuSig enables multisig participants to attach encumberances to the aggregated keys off-chain, which does not require Bitcoin’s consensus rules to be aware of it.

In December 2018, Anthony Towns was the first Core developer to make a _semi-_formalized proposal for the activation of Schnorr, which was posted on the bitcoin-dev mailing list. I expect more conversations about a potential softfork to come up in the following months.

To summarize: the first iteration of MuSig in Bitcoin will natively support key aggregation, which can immediately (1) improve the privacy of multisigs, (2) increase the efficiency of transaction validation, (3) improve security by eliminating the inherent problems of ECDSA, and (4) enable smart contract solutions like Taproot, which I plan to cover soon.

But this is just the beginning.

CROSS-INPUT AGGREGATION: THE NEXT STEP FOR BITCOIN PRIVACY

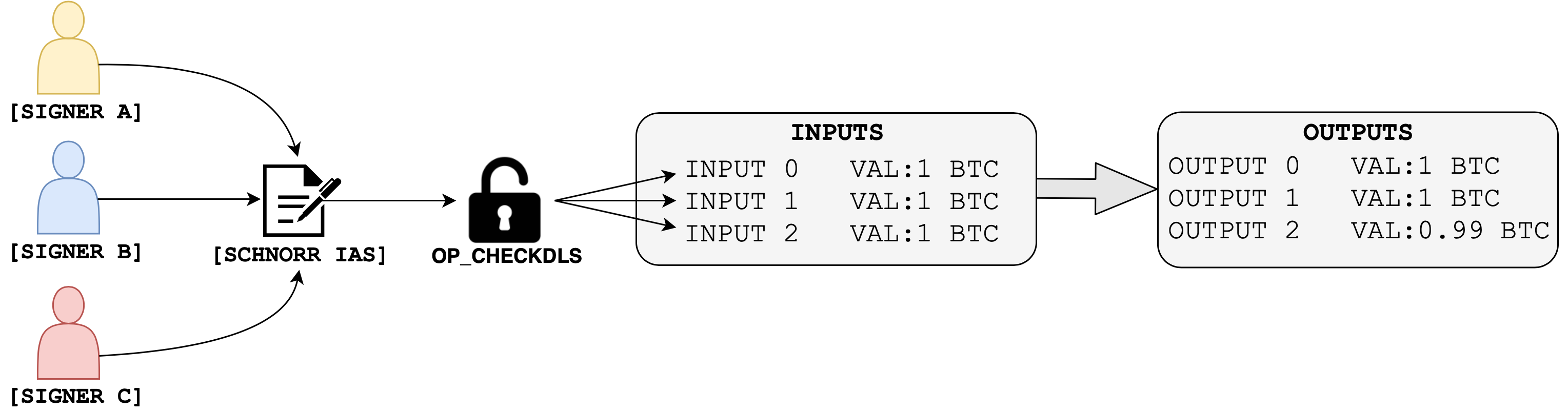

As covered in the last section, key aggregation is an incredibly useful feature for multisigs that spend a single input. Since Bitcoin transactions usually have more than one input, future iterations of Schnorr can also be leveraged to create an interactive aggregate signature (IAS) scheme, where all inputs in a transaction are spent simultaneously with a single signature.

Once again, the interactions between signers occurs entirely off-chain, but now, a single signature can be used to spend all inputs of a transaction. Each input would still have its own public key, but spendable by a Schnorr IAS:

Greg Maxwell, Pieter Wuille, Anthony Towns and others have been working on an evolution of the Taproot smart contract scheme to facilitate this functionality. They call this scheme Generalized Taproot, or G’root, and it can make the transition from key aggregation to cross-input aggregation much easier in the future.

Like key aggregation, cross-input aggregation further increases the efficiency of Bitcoin transactions. But, most importantly, it may enable strong privacy-preserving mechanisms on Bitcoin’s base layer.

One of the most exciting aspects of cross-input aggregation is the way it can improve CoinJoin transactions on Bitcoin. For context, CoinJoin is a privacy-preserving technique where multiple senders and receivers are combined within a single transactions. The goal is to make it difficult for a _blockchain observer _to link specific senders and receivers, thereby enabling the entities within the CoinJoin to claim plausible deniability.

This technique was originally proposed by Greg Maxwell on BitcoinTalk in 2013, and has since been offered through various services inlcuding JoinMarket, SharedCoin, ShufflePuff, DarkWallet and CoinShuffle. Variations of CoinJoin, such as the Chaumian CoinJoin scheme used in the Wasabi Wallet greatly improved upon the original model. However, since anonymity loves company, it still relies on a sufficiently large number of users to obfuscate their balances as well.

Another issue with CoinJoin today is the identifiability (and potential censoring) of the entire transaction type. Consider that the most used heuristic in blockchain analysis today is to follow specific inputs in order to determine if two or more addresses belong to the same entity. If Alice sent Bob 1.982723 BTC, for example, a blockchain observer could track the decimals of that specific input to map the transaction graph, or the historical breakdowns and changes of ownership of a UTXO.

To prevent that, CoinJoin implementations require common value denominations, whereby everyone within the CoinJoin sends the same amount. Users of the Wasabi wallet, for example, send the same denomination of 0.1BTC in CoinJoin transactions of 100 participants. Although it is still hard to pinpoint the connection between specific senders and receivers, the blockchain observer can look for common denominations to identify that a CoinJoin took place and advise its client to censor all entities involved.

Cross-input aggregation can help with that, as it introduces an additional obfuscation mechanism at the protocol level. In essence, **cross-input aggregation can enable the construction of Schnorr-based CoinJoin transactions with n _signers that look like regular, single-signer transactions to outsiders.** That may also enable CoinJoin to be more easily implemented in popular wallets without strenuous engineering, which may increase the network’s overall _anonymity set, or the number of users using this technique.

The common-denomination issue can further be resolved with additional techniques, such asPay-to-EndPoint (P2EP), which combines Satoshi’s early work on privacy (see P2IP) with CoinJoin, whereby both senders and receivers contribute inputs to a transaction. This novel technique deserves a standalone post, but you can read more about it here, here and here.

P2EP is backwards compatible, and when used in conjunction with Schnorr, it may enable sufficient privacy in Bitcoin’s base layer.

2 BIRDS, 1 STONE

It is reasonable to assume that Bitcoin’s mass adoption depends upon the strength of its privacy guarantees. At the same time, the popularity of the Lightning Network and its own potential to host private payments has also generated uncertainty about future demand for on-chain settlement after the last bitcoin has been mined. As such, the need for privacy and the long-term sustainability of Bitcoin without block rewards are perhaps two of the most most alarming issues surrounding Bitcoin today. Thankfully, the privacy mechanisms enabled by Schnorr can potentially address these two issues simultaneously.

I’ve spent thousands of hours reviewing sophisticated privacy technologies, including different implementations of Ring Signatures, Confidential Transactions, Bulletproofs, zkSNARKs, STARKs, and MimbleWimble. While some of these technologies are mature enough to be implemented on Bitcoin’s base layer, they still carry unique risks and trade-offs. As you have probably heard, Bitcoin is hard-fork averse, which makes it difficult to envision a scenario where any of these technologies get implemented at all.

A reoccurring concern people seem to have with the use of homomorphic encryption or non-interactive zero-knowledge proof systems is that they prevent the full audibility of Bitcoin’s monetary base. In other words, when transaction values are encoded, it becomes difficult to verify whether Bitcoin’s supply cap is, in fact, 21M BTC. Similarly, inflation bugs and double spends become harder to pin point when transaction amounts are hidden. This is a considerable trade-off, and a push for the implementation of cutting-edge privacy on Bitcoin’s base layer could divide the community.

But what if these technologies don’t even need to be implemented in order for Bitcoin’s base layer to gain _sufficient _privacy?

Schnorr can definitely help with that. If most Bitcoin transactions were to use Schnorr’s cross-input aggregation feature in conjunction with P2EP, it would be become nearly impossible to de-obfuscate specific senders and receivers over time by simply looking at the blockchain. Bitcoin’s supply would still be auditable, but its transactions would also provide much stronger privacy guarantees.

If there is demand for privacy, it is also reasonable to assume that Bitcoin users and businesses may want to engage in CoinJoin transactions passively, and let their wallets constantly mix their balances in the background. In this case, demand for privacy directly translates into an increase of on-chain transaction fees. Like SegWit, users will most likely champion the adoption of the technology at first, but businesses will have to follow suit at some point to remain relevant.

In time, the adoption of these technologies will make blockchain analysis obsolete and effectively removed from the _required _AML/KYC procedures that Bitcoin businesses are subject to, just like physical cash. When you deposit cash to your bank account, the bank won’t check the bills for traces of drugs and prevent your deposit if they find any. There is no reason why this is done with bitcoin, other the proliferation of blockchain analysis coupled with the shortcomings of techniques like CoinJoin without Schnorr.

When performing AML/KYC on specific addresses and UTXOs becomes irrelevant, and the focus turns onto individuals rather than balances, Bitcoin businesses will fully embrace privacy. In fact, I suspect that when that happens, privacy and fungibility will become an integral part of value proposition of future Bitcoin businesses.

Ultimately, the adoption of stronger privacy mechanisms on Bitcoin’s base layer will further empower its users and, at the same time, could contribute to the creation of a vibrant fee market after the last bitcoin has been mined. My guess is that it all starts with Schnorr’s activation, which everyone seems to be onboard with.

Further reading:

If you want more technical details on MuSig, Pieter Wuille’s blog post is a must-read.

Andrew Poelstra’s recent blog post on MuSig is also a great read and it describes the work on the Schnorr-compatible libsecp256k1-zkp.

If you want better privacy now, I highly recommend reading nopara73’s work on ZeroLink: The Bitcoin Fungibility Framework.

Eric Wall’s recent article on the state of privacy of Bitcoin is definitely worth checking out. It goes into the specifics of the common-input-ownership heuristic that is often used in blockchain analysis.

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |