It’s the settlement assurances, stupid

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

It’s the settlement assurances, stupid

How to evaluate blockchains

By Nic Carter

Posted July 22, 2019

What is the time to finality on major blockchains? How long should I wait before considering a Bitcoin transaction settled? What are the risk factors which might cause me to demand additional confirmations? How do confirmations affect settlement?

Surprisingly, none of these questions have good answers, even in 2019, over 10 years after the first Bitcoin block was mined. Rigorous investigation into the properties of proof of work has been hampered both due to a perception that it’s just a temporary staging ground for some future, superior consensus/sybil resistance mechanism, and due to a belief among Bitcoiners that its quality is inviolate.

But these questions are fundamental. If you believe that public blockchains with open validator sets and distributed convergence mechanisms will persist and mediate value transfer for the foreseeable future, they are worth pondering. And if you are an exchange and your livelihood depends on correctly assessing the number of required confirmations on a variety of blockchains, these questions are critical. First, let me explain why I think settlement assurances are the primary thing worth contemplating about any public blockchain.

What’s the interesting thing about Bitcoin?

This is a surprisingly difficult question to answer. Ask ten different Bitcoiners, and you’ll get a dozen different responses. Disagreements about what what Bitcoin is for, its teleology, nearly tore the community asunder in the 2014–17 period. Hasu and I tried to chronicle these competing visions in a piece a while back. Others have noticed this and have covered it in detail. I particularly like Murad Mahmudov and Adam Taché’s take. Daniel Krawisz covered the topic ably in 2014.

In Krawisz’ piece, he posits that Bitcoin is understood very differently by two major tribes: the investors and the entrepreneurs. The investors, he posits, believe that Bitcoin is a new form of high-powered money which primarily upholds the sovereignty of the individual. The investors tend to believe that Bitcoin will catch on because of the innate strength of its monetary properties. For them, evangelism is pointless: price is the best evangelist. The ‘entrepreneurs’, as he dubs them, are more interested in Bitcoin as a global payments system, and emphasize its use in commerce. As anyone who paid attention in 2015–17 knows, these two sides fought a bitter civil war over Bitcoin’s telos(purpose) with the block size being the main battleground.

Perhaps these views can be harmonized. I tend to believe that the interesting thing about Bitcoin is its capacity to facilitate the transfer of value through a communications medium with extremely strong assurances. (I made an effort to disentangle and evaluate those assurances here.) I think that Bitcoin is a novel institutional technology— high-assurance wealth storage and transfer without reliance on the State or a financial system — which will unlock new modes of human organization and will enable productive commerce in places where property rights are poorly enforced.

So if the assurances you get around settlement are the most interesting thing about the system, how can we evaluate them? And how do we make consistent comparisons between Bitcoin and other systems with open validation?

Evaluating settlement

So what are settlement assurances exactly? They refer to a system’s ability to grant recipients confidence that an inbound transaction will not be reversed. Wire transfers using a messaging system like SWIFT are popular in part because they are practically impossible to reverse. They are considered safe for recipients because originating banks will only release the funds if they are fully present in the sender’s account.

This is why the thieves behind the $1b Bangladesh bank robberyused SWIFT and bank wires; they wanted to leverage their settlement assurances. In other words, they chose to use a system for the theft which they knew would be hard to reverse. Ultimately, $61m from that heist remains unaccounted for. Far from being evidence of a failure of SWIFT + bank transfers, this demonstrates the system’s strengths. Even in this case, where virtually everyone involved wanted to reverse the transaction, they could not. The system is resistant to rollbacks, discretion, and post-hoc edits. This doesn’t make it a bad system. This makes it a system that gives counterparties a good deal of reassurance that a transaction will be final.

In a similar manner, Bitcoin is a useful system because it provides users powerful settlement assurances. Just how good, we don’t know exactly. LaurentMT wrote probably the most scientific exploration in his excellent Gravity series. Generally though, the properties of Bitcoin’s PoW have not been fully explored. It has suffered a few reorgs in its history, but, as far as we know, no deliberate, adversarial reorganizations where money was stolen. And we know that miners allocate a staggering amount of real-world resources into mining transactions. This means that recipients of a Bitcoin transaction can have extremely high confidence that, once buried under a few blocks, a transaction is unlikely to be reversed.

However, this isn’t the case for many competing cryptocurrencies. While they look cosmetically similar to Bitcoin in many cases, none have the same settlement assurances. This isn’t necessarily because of any design flaw, but simply because Bitcoin’s block space has more accumulated costliness — and hence cost to attack — per unit time, and because Bitcoin is a near-monopolist on its hash function and has dedicated hardware. Somewhat surprisingly, many weaker chains haven’t been exploited, even if the cost to do so has been low. This is likely to due to the fact that monetizing a 51% attack requires exploiting an exchange, which introduces additional complexities. And quite frankly, most smaller coins aren’t worth much in the first place (and don’t have any liquidity on the short side), capping the yield from an attack.

To get an idea of just how vulnerable many cryptocurrencies are, take a cursory look at crypto51.app. The methodology somewhat unrealistically assumes an attacker can rent sufficient hardware on Nicehash, but it still nicely depicts a lower bound of the cost to attack these systems.

So what are they key variables for evaluating settlement in a public blockchain system? Let’s divide them into to the easily quantifiable ones and the harder-to-quantify variables.

Before we jump in, let’s pause for a tiny literature review to credit some prior work in the space:

- For a much more succinct take on the matter, read Anthony Lusardi’s Understanding (and Mitigating) Reorgs.

- For a comprehensive investigation into the qualities of Bitcoin’s Proof of Work, see:Beyond the doomsday economics of “proof-of-work” in cryptocurrencies by Raphael Auer of the Bank for International Settlements

- For a fascinating implementation of a what a model incorporating some of these variables might look like, see A Lower Bound on Miner Rewards, by Kevin Lu of BKCM

Quantifiable settlement variables

Ledger costliness

Ledger costliness is the most profound and direct variable available to us to evaluate a blockchain’s settlement guarantees. Put simply, it is equivalent to the amount paid to validators/transaction selectors per unit of time. In Bitcoin, miners receive a per-block subsidy and transaction fees as an incentive to stay honest and “play by the rules.” In proof of work, miners attach an unforgeable proof that they have burned some energy and hence incurred a cost to each block proposed. At the time of winning a block, the miner necessarily has to have burned resources roughly equivalent to the value of the block (typically with a small margin), unless they are extraordinarily lucky. Because of this, miners are incentivized to create valid and rule-following blocks.

Think of it as a bit like a school project where you had to read a book and produce a book report. You need to prove to your teacher that you read the book, so you produce a book report (a valid block hash with a sufficient number of leading zeroes) which you could only have created if you actually read the book (computed sufficient hashes). Because your teacher is a stickler for style, you also have to format your book report correctly (produce a well-formed and valid block). It would be a tragedy to read the whole book, only to present a digest which is malformed and ends with you getting an F. Proof of work is the same: the work is upfront, with the payoff only coming later. You’ve incurred a real cost, and your business depends on you carrying out the final bureaucratic steps to collect your reward, so you do your best not to screw that part up. Recently, a miner did all the requisite work to be eligible for a block but fell at the last hurdle by creating an invalid block.

For a more complete description of how the PoW incentive works, read Hugo Nguyen’s piece:

So why does more ledger costliness per unit time mean more security for transactors? Because a greater salary to miners (who are presumed honest) means you need a larger army of mercenaries to defeat them. These resources have to come from somewhere: you need to marshal resources and hardware capable of producing hashes, electricity, and so on. (There’s an argument out there that since attackers collect the subsidy when 51% attacking, only fees provide security in PoW. I don’t have the space here to engage with this fully here—for now I’ll just maintain that the subsidy, especially with dedicated hardware, is itself an enormous cliff which must be scaled before 51% scenarios can be theorized.)

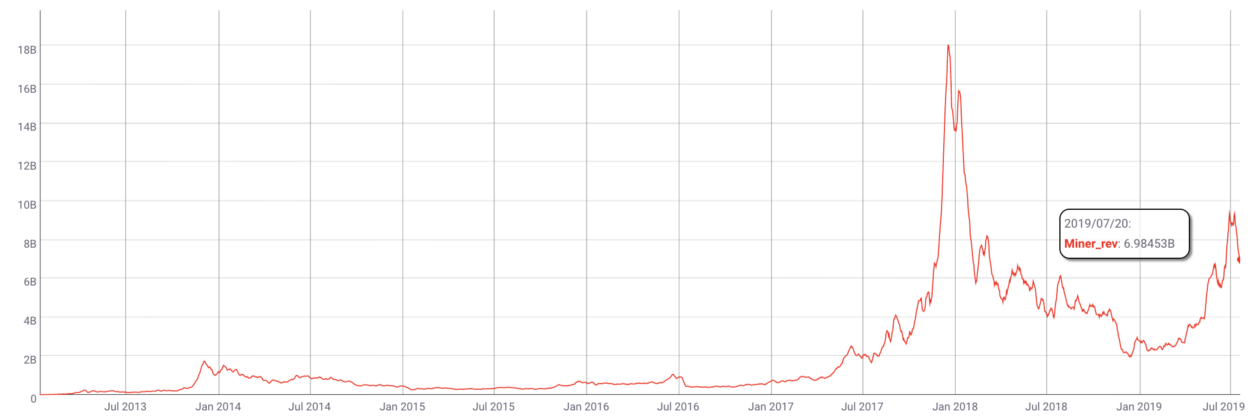

To sum up, outbidding the set of honest miners dutifully producing blocks on Bitcoin is very expensive. They collectively take a salary of $6.9 billion dollars per yearright now, and many of them have presumably invested in their businesses in anticipation of future cashflows (meaning that the hardware active on the network might be even higher than current miner revenue would imply).

Annualized Bitcoin miner revenue, USD terms. Data: Coinmetrics.io

Annualized Bitcoin miner revenue, USD terms. Data: Coinmetrics.io

So Bitcoin is protected not only by the daily salary that the protocol pays its miners, but by the discounted rewards these miners expect to earn in the future. This means Bitcoin isn’t just protected by the reality on the ground today, but miner expectations about rewards in the future.

We don’t have an easy way to model expectations, so the easiest thing to do is to simply take the miner salary per unit time and compare blockchains on that basis. If you stopped reading this article now and just retained that one sentence, you would already have a better understanding of security than most people. Very few entities, even those for whom the stakes are very high like exchanges, bother benchmarking blockchains like this.

Usefully, Anthony Lusardi has already done some great expository work on the topic. He introduces the BitConf — demonstrating how many confirmations are required for one Bitcoin confirmation’s worth of security on other blockchains, like Litecoin.

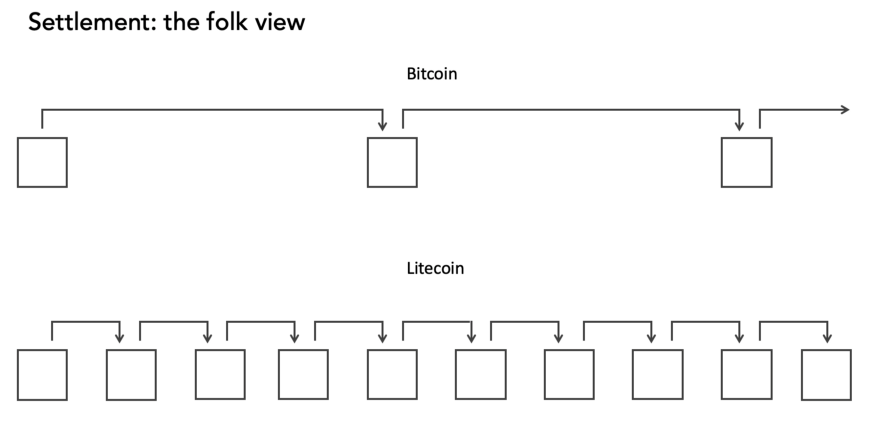

Suffice to say, most people do not use BitConfs, or try to index settlement to work done. Quite the contrary, the ‘folk theory’ of settlement holds that settlement is a linear function of the number of confirmations. This is sadly a very common view. Even the Litecoin Foundation website implicitly makes this claim:

Litecoin transactions are confirmed faster than other cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin because it generates a block every 2.5 minutes as opposed to Bitcoin’s 10 minutes. This means your money gets to its destination quicker.

The initial moment when a transaction is plucked out of the mempool and included in the chain is indeed reliably faster in Litecoin, but in cryptocurrency probabilistic settlement must be contemplated. In other words, if you only care about the first confirmation, then Litecoin is “faster”, but the moment you start to care about longer term settlement (over multiple confirmations), it becomes clear that it is much slower.

If you believe that Litecoin and Bitcoin confirmations confer the same amount of settlement guarantees, then you might depict settlement as follows, with Bitcoin apparently slower:

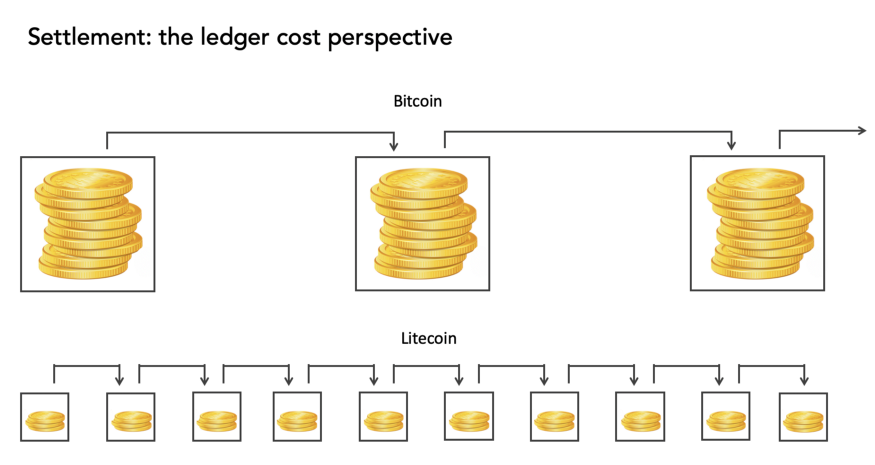

But this is mistaken. Litecoin has more blocks per unit of time, but it accumulates ledger costliness much more slowly. In reality, Bitcoin pays its private army of miners far better, and as a consequence, they produce far more security per minute in the form of hashes.

Bitcoin blocks are ‘heavier’ with accumulated cost than Litecoin blocks are. Even if Litecoin had a 10 minute block-time, a Bitcoin block would still be worth 14.5 times more than its Litecoin equivalent. Confirmations don’t really matter. The opportunity cost incurred by miners per unit of time does.

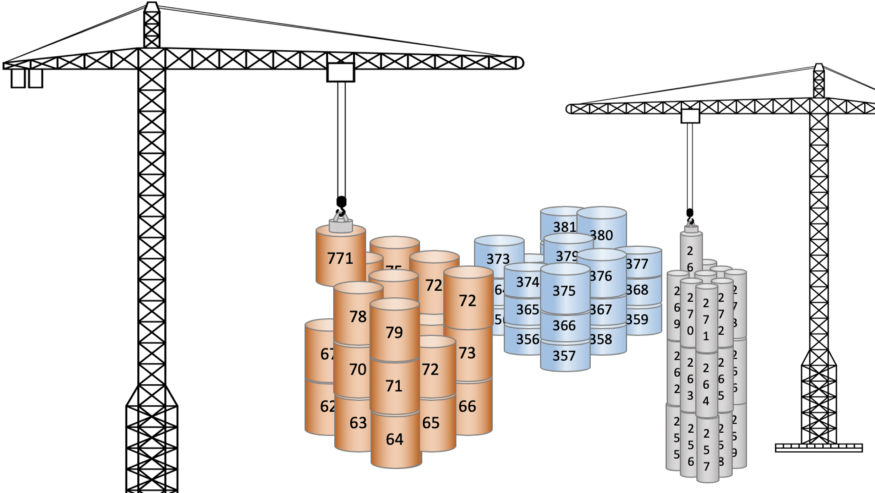

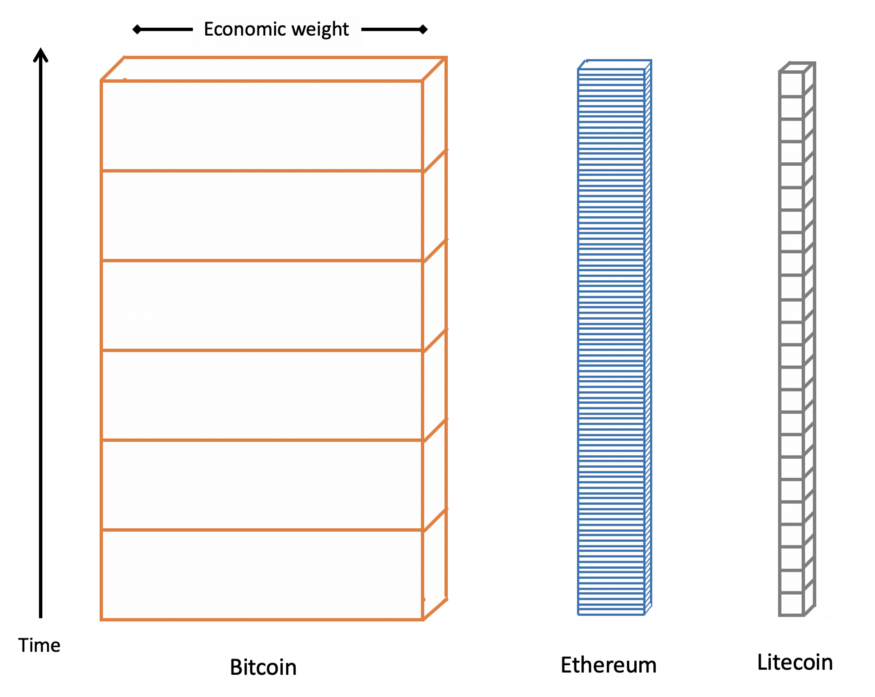

You could alternatively visualize ledger costliness as blocks getting piled on top of their predecessors, with transactions getting more and more final as they are buried deeper and deeper in the pile of blocks.

Block width is roughly proportional to the relative security spend of each blockchain

Block width is roughly proportional to the relative security spend of each blockchain

As more and more blocks get added to the heap, it becomes more and more implausible that they would be reverted, and transactions become more final. In this graphic I’ve scaled the width of blocks to the relative ledger cost incurred, and depicted the granularity of blocks.

The point here is that settlement in a blockchain system is a flow. Block time is largely irrelevant. Ethereum has many more blocks per hour than Bitcoin does, but settlement should be compared between the two based on ledger cost, rather than number of confirmations.

Yield from reversal: transaction size

Ledger costliness isn’t the only thing that matters in settlement. Also important is the incentive someone might have to try to reverse a transaction. The purest codification of this incentive is simply the size of the transaction. If you are a recipient of a 50,000 BTC transaction, you might wait more than the six block rule of thumb out of an abundance of caution. If you are receiving 1000 sats, one confirmation is likely sufficient. In short, transactions have more or less perceived settledness based on the stakes at hand.

Elaine Ou formalized this concept in a fantastic Bloomberg article, arguing that recipients should wait until the transaction’s value and ledger costliness matchto consider a transaction settled.

Elaine’s formulation handily conjoins two of the most important quantitative variables in blockchain settlement: ledger cost and yield from reversal. If you wanted to settle a $10m inbound transaction in BTC, according to this rule, you’d wait 60 blocks, or 10 hours. (It’s a neat coincidence that at a price of $13,330 Bitcoin accumulates ledger costliness at a rate of exactly $1m/hour). Henceforth, I’ll refer to this simple formula as the Ou Rule.

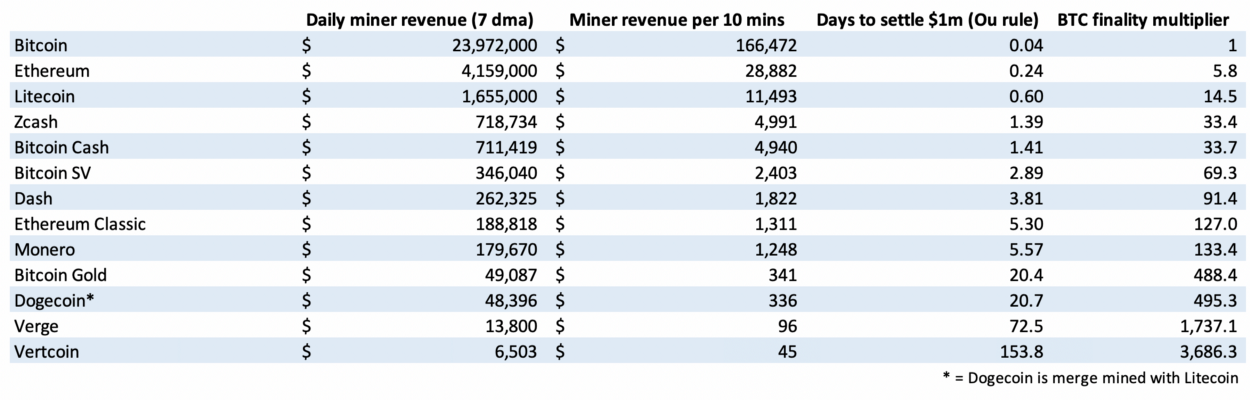

Now that we have the two most critical settlement variables enumerated, let’s put down some numbers and compare the major PoW networks.

Numbers as of 07/15/2019. Data: Coinmetrics.io

Numbers as of 07/15/2019. Data: Coinmetrics.io

Needless to say, Bitcoin is by far the fastest-settling blockchain (just including these two variables and none of the other salient ones). Settling even a $1m inbound transaction can be extremely slow on many blockchains. Aside from Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Litecoin, it takes over a day for every other decentralized ledger (I’m not including Ripple and Stellar in these examples because they don’t have meaningfully decentralized validation). Smaller chains simply do not have enough miner reward to make settlement suitably quick.

Luke Childs’ Howmanyconfs offers a dynamically updated version of parts of this table:

How Many Confs? How many confirmations are equivalent to 6 Bitcoin confirmations? howmanyconfs.com

It’s also worth calling attention to the fact that Bitcoin Cash and Bitcoin SV settle transactions 33 and 69 times more slowly than Bitcoin, respectively. While they are functionally identical to Bitcoin in most respects, because they offer miners less of a bounty, they are vastly slower. This directly contrasts with their common positioning as “faster” blockchains.

This is also an interesting case study in how Bitcoin resists duplication. You can create something which looks cosmetically similar to Bitcoin, but you cannot replicate the settlement assurances which derive from the costliness of the ledger. Miners obey economic reality and cannot be cajoled to lend their support to a protocol which doesn’t pay them well enough. In fact, as we will learn, Bitcoin Cash and Bitcoin SV are even worse off that this table suggests, because of a third variable.

Monopolist on its own hash function

So far, I haven’t mentioned a third critical variable which directly affects the settlement guarantees of a given blockchain: whether or not it holds an effective monopoly over the hardware which is addressable to its hash function. As I implied above, Bitcoin Cash and Bitcoin SV are at a massive disadvantage relative to Bitcoin because they have a minute fraction of all the SHA-256 ASICs. What this means is that even a mid-size or small pool mining Bitcoin could temporarily redirect its hashpower to one of Bitcoin’s smaller forks and 51% attack it at will.

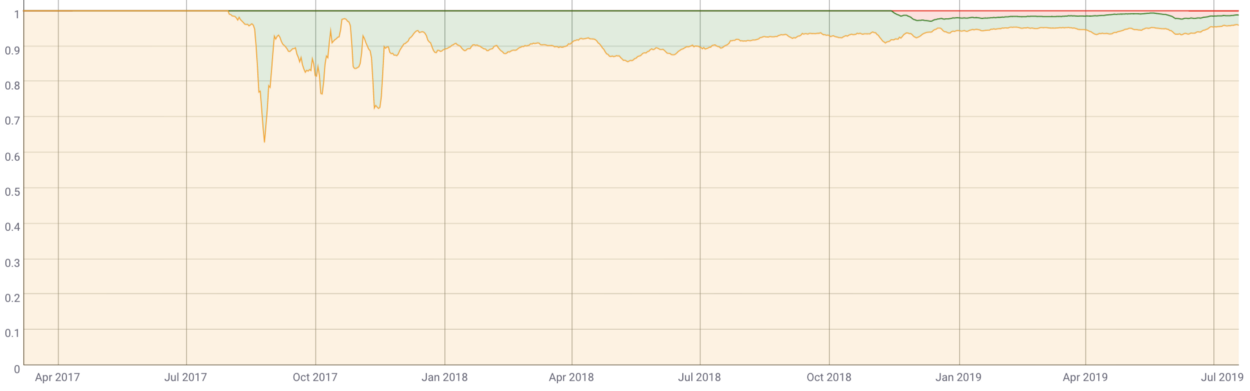

Relative share of miner revenue; BTC (orange), BCH (green), BSV (red). Coinmetrics.io

Relative share of miner revenue; BTC (orange), BCH (green), BSV (red). Coinmetrics.io

The fact that these blockchains have not been attacked yet is not evidence of their security. It may well be the case that there are no miners on Bitcoin willing to maliciously interfere with either minority fork today — but depending on the goodwill of miners makes for an extremely tenuous security model. Since this risk is ever-present, it could be posited that neither blockchain ever reaches effective finality, regardless of the number of confirmations. This is because there are ample mining pools on Bitcoin which could create a 100+ deep reorganization in BSV for instance without too much difficulty.

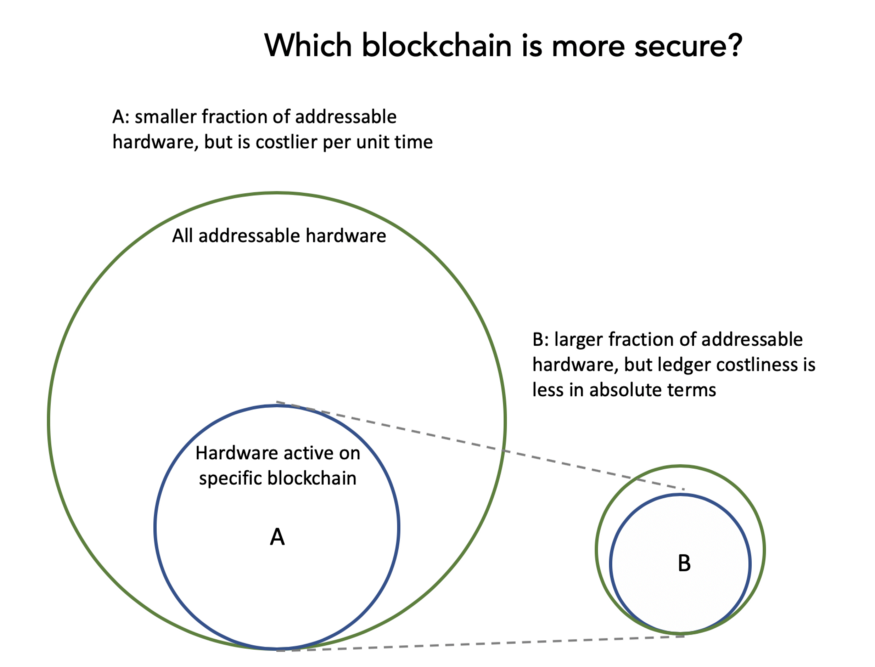

This variable introduces more complexity into the analysis. It is not the case that more hashrate means that a blockchain is more secure; it must also occupy a large fraction of the addressable hardware.

In this example, I’d characterize blockchain A as less secure than B, even though it has more ledger costliness in absolute terms, because it is theoretically easier to marshal enough hardware to attack A.

So consider this variable to be a boolean; if the blockchain is a monopolist on its own hardware the analysis is straightforward. If it is in the unfortunate position of splitting hardware with one or many other blockchains, and retains a minority share of that hash-function-specific hardware, it is likely fundamentally unsafe. But it’s hard to determine just how unsafe it is; the risk of an attack is a function of the attackers ability to amass sufficient electricity and hardware.

Less quantifiable settlement variables

The three variables mentioned above aren’t exhaustive, but simply the easiest to quantify. With those, you could probably build a plausible model which is superior than those used by many exchanges today. But there are many more factors to consider.

Yield from reversal: goldfinger attacks

Goldfinger attacks take their name from the Bond film in which the villain plans to irradiates all the gold in Fort Knox, making all of his gold more valuable. The term describes a class of attacks where the attacker is motivated by some extra-protocol financial interest. Joseph Bonneau more scientifically describes themas attacks where the “attackers [have] an extrinsic motivation to disrupt the consensus process.”

The risk of these attacks is virtually impossible to quantify, since attackers have a variety of different motivations, and they tend not to disclose them a priori (before an attack). Here I’ll give two further examples where the yield from reversal dramatically increases, rendering settlement guarantees less certain.

Top Heaviness

This refers to the condition in which a large number of financial significant assets are created as tokens on top of some base layer protocol — for instance Omni assets on Bitcoin or ERC20s on Ethereum. As these tokens inherit their security from and are wholly dependent on the base layer, they are vulnerable to attacks on the underlying chain.

As the asymmetry develops between the value of the instruments on top and the cost to attack the base layer, the top heaviness problem starts to manifest. If the asymmetry becomes large enough, an attacker might seek to take out a short on some instrument on the top layer and simultaneously attack the base layer, either by mining empty blocks and DOSing the tokens in question, or creating reorgs and confusion.

We have real world examples of the consequences of top-heavy systems. Attackers have recently made a habit of attacking the underlying index which sets the price for derivatives on Bitmex. Since there’s a big asymmetry between the collateral present on Bitmex (the top) and the underlying reference market (the bottom), it’s lucrative to burn funds market-selling on Bitstamp because the attacker can monetize by causing an outsize move on Bitmex as margin positions are liquidated.

I don’t believe any blockchain faces this problem today, but as more instruments are tokenized and inserted on top of blockchains the returns from attacking the base layer will increase.

Liquid derivatives markets

This is rather straightforward. Derivatives, options in particular, give financial market participants the ability to obtain leverage and magnify their returns even relative to a small move in the underlying. As with the top heaviness condition, the risk to the blockchain comes when a significant asymmetry exists between the cost to mount an attack and the returns from an attack.

The creation of liquid derivatives markets enables attackers to magnify their returns from predicting price action; and if they can induce a drop in the price of the asset by mounting an attack, the settlement guarantees of the chain are potentially at risk. As the return from an attack grows, so does the amount of resources that an attacker is willing to contribute to an attack. So the creation of leverage on the short side potentially impairs a blockchain’s settlement assurances. But due to the heterogeneity of actors and uncertainty about the ability to monetize such an attack, it’s impossible to quantify this risk and add an appropriate security discount.

Of course, one counterbalancing factor here is the potential unwillingness of an exchange to pay out on a successful bet if they suspect that the trader in question was coordinating with an attacker to interfere with the blockchain.

Additional hardware considerations

Implicit in the earlier point on hash function-specific hardware is the well-documented notion that GPU-mined coins cannot ever be monopolists on their hardware because there are so many GPUs in the world (thanks to gaming and other non-cryptocurrency applications). I won’t belabor this point: David Vorick has cleanly laid out the case for why GPU-mined chains are fundamentally at risk, and why long term incentive-alignment (in the form of ASICs) is so critical.

Thus GPU-mined coins should always be assessed additional confirmations. It’s hard to know exactly what the ratio should be for one GPU-mined unit of ledger costliness to an ASIC-mined unit. But there absolutely should be a discount for GPU-produced security. It’s simply too easy to acquire hardware to mine a GPU-mined chain.

Case study: Kraken’s confirmation requirements

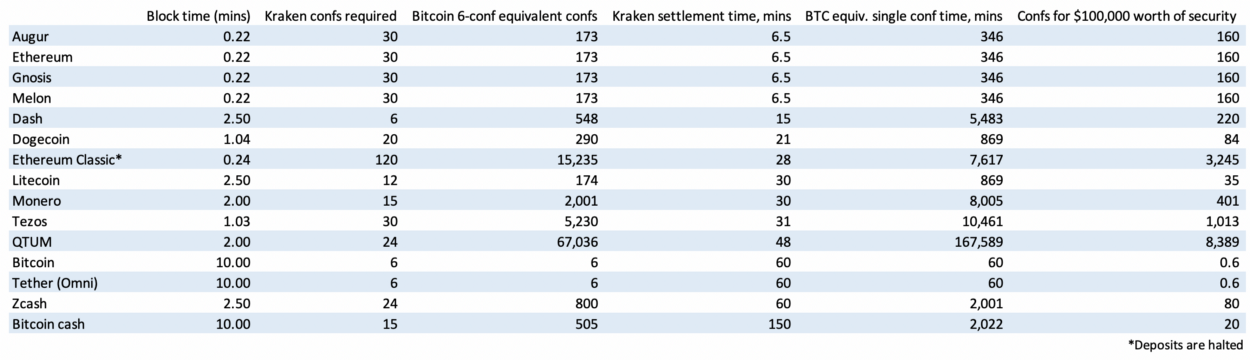

Startlingly, from my conversations with exchanges, who have a lot to lose from miscalibrated rules around settlement, it appears to me that they tend to give little thought to confirmation rules. I couldn’t find much detail on how many inbound confirmations exchanges reserve until a transaction is considered settled. Helpfully, Kraken have made their criteria freely available.

I decided to benchmark Kraken’s confirmation requirements against what a naive implementation of Lusardi’s BitConf would look like — simply requiring that all chains provide the equivalent of six confirmations on Bitcoin.

Source: Kraken Deposit Processing Times, Coin Metrics estimates

Source: Kraken Deposit Processing Times, Coin Metrics estimates

The results are startling. Depending on how you put it, Kraken makes either extremely stringent demands of Bitcoin transactions, or extremely loose demands of non-Bitcoin chains. While Kraken asks for six Bitcoin confirmations to consider deposits settled, they ask a mere 12 of Litecoin (where the equivalent in Bitcoin security terms would be 174), 30 for Ethereum (Bitcoin equivalent: 173), and 15 for Monero (where Bitcoin-indexed security would demand 2000).

My guess is that six confirmations is massive overkill for Bitcoin, making Kraken’s lesser settlement demands of other chains more reasonable. Still — when the ledger costliness variable is consistently applied, the results are occasionally comical. QTUM, for instance, if held to the same standard as Bitcoin, would need 67,000 confirmations, equivalent to a wait of 115 days. (QTUM may well have some alternative settlement mode I’m not familiar with: I computed the numbers simply based on the payouts it makes to validators).

Of course, this is a very naive implementation of the model. A more sophisticated version would include higher security demands for non-monopolist chains, GPU-mined coins, large inbound transactions, and so on. I would encourage exchanges like Kraken to consider a systematic ruleset for inbound transactions, if they don’t already. Whatever the particular formula chosen, it would likely suggest fewer confirmations for Bitcoin and more for smaller chains.

Some takeaways

What’s the practical significance of all this? Well as we continue to await the formalization of these variables into a model that makes sense and is directly applicable to everyday usage of cryptocurrency, here are a few takeaways:

I. Block time is arbitrary, and changes little

The only thing that a lower blocktime alters is reducing variance in the time to the initial confirmation. If you are impatient, you probably prefer a blockchain with a 2.5-minute blocktime, but this doesn’t mean that settlement is any “faster”. Ledger costliness still accrues at the same rate, being a function of issuance and unit value per coin.

Indeed, Bitcoin could reduce its block size by 25% and switch to a 2.5 minute blocktime and virtually no one would notice the difference. The system would be functionally identical — the six block rule of thumb would become a 24 block rule of thumb. Satoshi opted for 10 minute blocks because he did not know how well the system would be able to come to convergence. Latency and large blocks interfere with validation, and make convergence among nodes more difficult. A healthy 10-minute blocktime gives the system plenty of breathing room — and also gives us an indication of what kind of a system Satoshi was envisioning (hint: not suited for in-person, petty cash payments).

It’s true that the first confirmation matters some small amount, since your transaction cannot start to be buried under the weight of subsequent blocks until it is included in a mined block. Additionally, a lower blocktime reduces variance in variables like daily issuance. However, aside from that, blocktime is completely arbitrary. The security spend per unit of time, in addition to the quality of that ledger costliness, is what matters for settlement. A lower blocktime just means that you’re chopping up that security flow into smaller bits. It doesn’t make final settlement any faster.

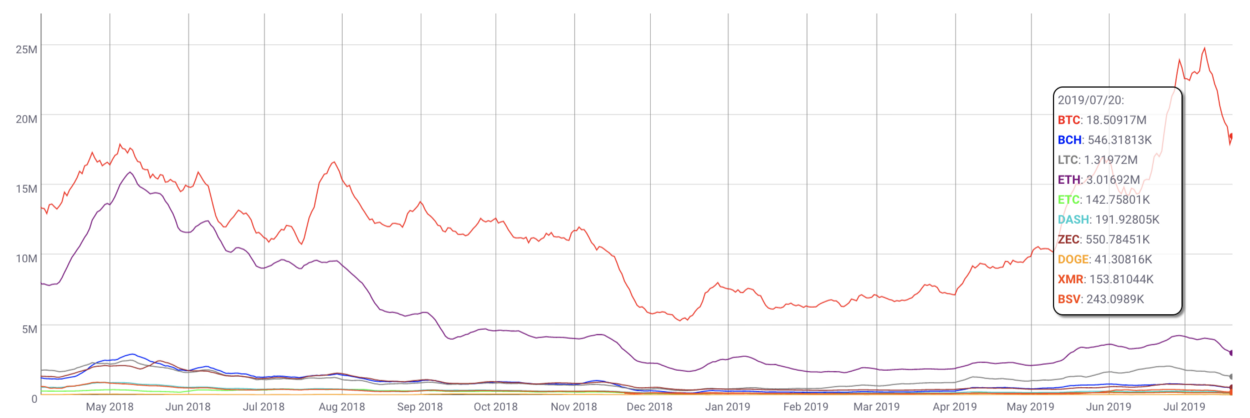

II. Bitcoin is either providing massive security overkill, or other blockchains are critically at risk

This is the clearest takeaway from the various benchmarking exercises I did for this article. If you measure blockchains purely based on the salary paid to transaction selectors (miners and validators) per unit of time, for the most part, they look devastatingly weak compared to Bitcoin. Just have a look at this chart. Aside from Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Litecoin, virtually nothing is visible on the chart, because their security spend is so minimal.

Daily USD miner revenue, smoothed (7dma). Coinmetrics.io

Daily USD miner revenue, smoothed (7dma). Coinmetrics.io

This isn’t necessarily fatal. It could be the case that Bitcoin is way overpaying for security, for instance, and that proof of work is ‘better’ than we think. This is actually my current view — that due to the current subsidy conjoined with the high unit value of Bitcoin, Bitcoin is probably spending “too much” on security. But it does wrap the protocol in a warm blanket which gives it a good degree of protection as it enters its teenage years.

So this data is not necessarily apocalyptic for smaller blockchains. After all, even though Satoshi ordained the six-block rule of thumb, it could be the case that for most transactions 1 or 2 blocks are sufficient. This would lessen the heavy load placed on other blockchains trying to match Bitcoin’s security spend.

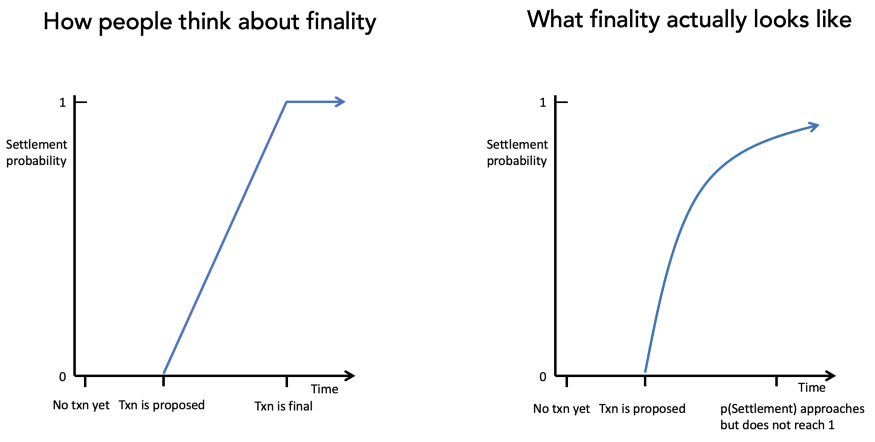

III. Settlement is always probabilistic

I will admit that I chafe a little bit when new blockchains tout their ‘absolute finality’. The only way to truly have finality is to have an organization vouch for transactions, effectively endorsing them. But when this happens, authorities that might have an interest in reversing transactions (say if they suspect they are related to criminal activity) will typically ask that entity to facilitate the rollback, poking a hole in the perceived finality.

Take the example of EOS. EOS has a concept called the Last Irreversible Block which, according to EOS Canada,

[M]eans that you can trust with 100% confidence that that transaction is final, fully confirmed, and immutable. If the block number of a block is lower than the Last Irreversible Block, that means it is considered final.

According to EOS Network Monitor, the current Last Irreversible Block is trailing the chaintip by 330 blocks, equivalent to about 2 minutes and 40 seconds. All together, this makes EOS’ claimed time to finality very short.

Except there’s a catch. EOS has (had?) a bureaucratic process through which individuals could appeal to the ‘EOS Core Arbitration Forum’ and ask for funds from suspected thefts to be frozen and returned to the victims, effectively reversing long-settled transactions. One batch of these reversals took place in June 2018. This was possible because there were only 21 entities (the block producers) tasked with processing transactions, and all were known to the leadership and hence accountable.

While many onlookers cheered the return of stolen funds, from a settlement perspective this undoes the qualities that transactors seek when they use a blockchain. In practice, any mechanism which can reverse settlement can be abused. The reason credit cards embed a fee into transactions is because chargeback fraud is rampant.

Imagine a sophisticated scam where someone sold EOS for fiat in a p2p transaction, and then appealed the transaction to the ECAF, and managed to get the EOS in the transaction returned to him under the guise of having been scammed. These are the kind of schemes that result from administrative exceptions to finality.

There are any number of examples I could give on this topic, but I’ll stick with one for now. In practice, many of the blockchains that claim to have full and effective finality also insert the capacity to create discretionary rollbacks and account freezes into their systems. You still have to consider the probability of a reversal, even if it’s not explicitly codified.

IV. By being open about its security model, Bitcoin’s PoW is usefully transparent

Echoing Elaine Ou once again, one of the most useful features of Bitcoin’s security model is how transparent and easily apprehensible it is. The precise guarantees are not easy to determine (“how many confs to settle $1b?”) but the resources being spent to backstop the system are. At any point, an onlooker can trivially determine how many hashes, and by rough extension, how much energy, it would take to overpower the system. For years now, it has been clear that no entity outside the most potent state actors could muster sufficient resources to outweigh the honest majority.

By contrast, other blockchains seek security through obscurity, security through complexity, or through untransparent institutional modes of finality. Verge, for instance, conjoined five different hash functions in its exotic proof of work model, and that was ultimately its downfall. An attacker realized they could perform a ‘time warp attack’ by targeting just one of the hash functions and lowering difficulty to 1. Far from providing extra security, the insertion of more complexity into the system introduced new attack vectors.

Summing up

If there’s anything I could have you take away from this piece, it’s the following. Instead of viewing settlement as a function of some preconceived number of confirmations, think of settling a transaction in a proof of work system as the process of wood petrifying slowly. It happens at a given rate and can’t be accelerated. The rate is determined by the variables enumerated above: chiefly, ledger costliness, transaction size, and the availability of addressable hardware. Once completed, the wood has been replaced by minerals and is rock solid, no longer soft and malleable. The features of the wood are forever frozen in time.

Similarly, as Nick Szabo has said, blockchains are computational amber. Amber starts life as tree sap, only later becoming hardened, in the process storing bits of information (insect DNA and so on) within it. The essential process of burying past changes to the ledger under unforgeable cost, provided by proof of cost incurred, provides the same slow-moving settlement assurances. As more blocks accumulate, the gravity of the blockchain exerts itself, and makes distant rewrites colossally expensive and unwieldy.

The bounty available to miners — and hence the cost incurred — is a function of issuance, unit price, and fees. None of these aside from issuance can be directly programmed. And a high issuance alone cannot guarantee security, as investors have to buy into the chain’s prospects and backstop its value. In this sense, strong settlement assurances in a proof of work system cannot be planned for, they can only emerge. Whether you find this to be a dismal conclusion or not is up to you.

In this article, I tried to enumerate the variables which I believe are most critical for evaluating the settlement assurances of blockchains, especially those built on proof of work. But you’ll notice I provide no formal model nor a recommended solution to the problem. Many of these variables cannot be easily quantified and there are likely some which I am leaving out. A more comprehensive — or implementation-focused — model I will leave to subsequent authors.

If we ignore these questions, they will be forced upon us through necessity. As short-side liquidity emerges for a larger share of the market, whole new classes of attacks will open up and exchanges will find themselves targeted more and more. Equally, as major custodians and clearinghouses start to take cryptocurrency deposits totaling hundreds of millions or billions, they will need to devise formal rules for what constitutes settlement. They would do well to think deeply about the security of the blockchains that they are reliant on.