How to scale Bitcoin (without changing a thing)

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

How to scale Bitcoin (without changing a thing)

Why Bitcoin banks need to prove their solvency

By Nic Carter

Posted April 14, 2019

Almost from inception, the “scaling debate” in Bitcoin, and cryptocurrency more generally, has been framed in what could be called Hegelian terms.

- Thesis: peer-to-peer cryptocurrencies are useful for online commerce

- Antithesis: online commerce requires millions of transactions a day

- Synthesis: to succeed, cryptocurrencies must scale

This has been the default backdrop for discourse in the industry and the onlooker press for the better part of the last decade. In this piece I’ll posit that this obsession, which has driven discourse in Bitcoin land for the better part of a decade, misses the point, and I’ll suggest an alternative framing. I believe that institutional scaling presents an under-appreciated scaling vector, and it is quite possible to employ it without significantly compromising Bitcoin’s assurances.

By this I mean the Finneyan view of Bitcoin in which Bitcoin banks emerge and issue notes against deposited Bitcoin. If you look carefully, a proto version of this system is in place today. However, for cherished assurances like scarcity to be upheld, exchanges and custodians need to start making routine attestations that their reserves match their liabilities.

Before we start, a tiny literature review (optional):

- Spencer Bogart on Bitcoin’s strong assurances

- Hasu on how Bitcoin supports non-state property rights

- Yours truly on the quality of Bitcoin’s touted assurances

- Jameson Lopp on the exact technical guarantees and near-guarantees that PoW gives you

- Davidson, De Filippi, and Potts on how public blockchains are a new type of institutional technology

- Saifedean Ammous on how Bitcoin could function solely as a settlement network

Prescience on the mailing list

The very first public comment on Satoshi’s white paper, coming as a response on the cryptography mailing list five hours after publication, was this astute observation from James A. Donald:

If hundreds of millions of people are doing transactions, that is a lot of bandwidth — each must know all, or a substantial part thereof.

What James understood is something that has escaped many who scampered down terabyte-block rabbit holes: Bitcoin only works because anyone can retain a copy of the ledger and stay in sync. If you make syncing with the current state of the ledger too expensive, only a privileged few can stay up to date, effectively adding a hierarchy to a system which must be flat to function.

Satoshi’s answer to this question, interestingly, involved SPV proofs, which, bathed in a present-day epistemic light, appears somewhat naive. SPV proofs ostensibly allow a non-full node to know that a transaction has been included in Bitcoin without downloading the whole chain. Casually invoking SPV proofs as the solution to scaling is a bit like the scientists behind the Apollo program remarking: “Oh, a trip to Alpha Centauri? Just the simple matter of faster than light travel.”

Suffice to say, SPV proofs have been virtually abandoned as a viable scaling method today. Under a variety of scenarios, they tend to collapse into users having to validate the entire chain anyway.

James was spot on. He immediately understood that Bitcoin was a single ledger which all of the nodes in the network had to continuously reaffirm at 10 minute intervals. Since everyone had to see everything, hundreds of millions of transactors would simply overwhelm the system.

But what if this teleological premise — Bitcoin is for global, online, peer-to-peer commerce at the individual level — was flawed? Enter Hal Finney.

Stairway atop Diana’s Peak, St Helena

Stairway atop Diana’s Peak, St Helena

Hal’s vision

In 2010, digital cash pioneer Hal Finney famously made the case for what could be called the institutional approach to scaling Bitcoin.

Actually there is a very good reason for Bitcoin-backed banks to exist, issuing their own digital cash currency, redeemable for bitcoins. Bitcoin itself cannot scale to have every single financial transaction in the world be broadcast to everyone and included in the block chain. There needs to be a secondary level of payment systems which is lighter weight and more efficient. Likewise, the time needed for Bitcoin transactions to finalize will be impractical for medium to large value purchases. Bitcoin backed banks will solve these problems. They can work like banks did before nationalization of currency. Different banks can have different policies, some more aggressive, some more conservative. Some would be fractional reserve while others may be 100% Bitcoin backed. Interest rates may vary. Cash from some banks may trade at a discount to that from others.

In a brilliant stroke of foresight, Hal understood that base layer Bitcoin would never scale to the desired level in its current format. (Unfortunately, many Bitcoin evangelists failed to understand this, and their misapprehensions led to the bitter blocksize wars of 2015–17.) In Hal’s view, Bitcoin would be a high-powered money mediating large settlements between financial institutions, rather than a payment token used for the online equivalent of petty cash payments. He realized that Bitcoin’s rather slow settlement times (compared to physical cash or credit cards) combined with the inefficiency of the chain itself meant that directing Bitcoin to the brick-and-mortar payments use case was a square peg in a round hole.

What Hal envisioned was a system where banks could be auditable, transparent in their capital ratios, and accountable. A free market for reserve/capital ratios could even develop, as depositors would be able to select banks with varying levels of reserves to suit their risk preference.

Undercapitalized banks might fail — but this would be a healthy market signal, a culling of weaker entities to render the herd stronger overall. Compare this to the system that became unraveled in 2008/09: financial institutions heaping on leverage, knowing that they would be bailed out if something went wrong. Since the government made it clear that it would not allow banks to fail, the market was robbed of that valuable feedback mechanism and risk became increasingly abstracted, obscure, and hidden.

In the words of Elaine Ou:

Financial institutions make people feel safe by hiding risk behind layers of complexity. Crypto brings risk front and center and brags about it on the internet.

In finance, risk never truly disappears, even if hidden — and suppressing it often has the nasty effect of unleashing it in a more dramatic fashion later on.

Just as risk crept up on us, unheralded, and financial institutions failed one after the next in a cascade of toxic balance sheets in 2009, so too will the long-suppressed forces of systemic risk unleash themselves when our present monetary experiment finally unwinds.

Can Bitcoin mollify this? Perhaps not. But its very structure facilitates the creation of an alternative financial system which is far more transparent and open about risk than the present one. This is the Finneyan view of Bitcoin: Bitcoin as a virtual commodity sitting in provable reserves in financial institutions. No one’s liability, a provable virtual commodity which a bank can rely on to attest to its viability.

Winding road through Glencoe, Scotland.

Winding road through Glencoe, Scotland.

Scaling assurances

Let’s briefly revisit what we mean by scaling, anyway. It’s clear by now that simply opening up the block space throttle doesn’t work. This is because Bitcoin is designed to be auditable, and auditing the blockchain requires the full, unabridged ledger.

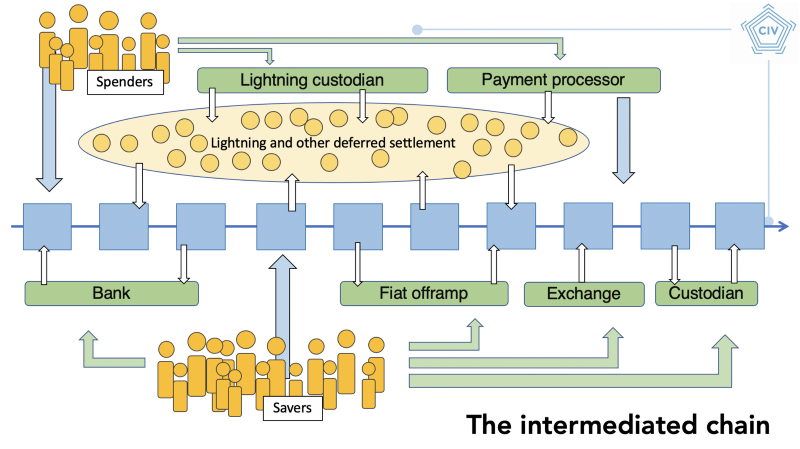

Fundamentally, Bitcoin relies on everyone being aware of every transaction. Can this be scaled without compromising this core feature? Let’s see how the major classes of scaling innovation fare under this lens:

- Deferred settlement/reconciliation(chiefly lightning). What lightning and other defer-reconcile models of transacting do is grant users the ability to create relationships which are then settled at a later date. The chain’s assurances are still present and available, they just aren’t employed for each transfer. These models do however trade off by (temporarily) weakening assurances — final settlement is no longer instant and you have to be online to receive a payment, for instance.

- Database model (massive base layer scaling). As mentioned, simply increasing the ledger size compromises the assurances of the blockchain — not everyone is able to maintain the ledger. There may be a way to do this in a trust-minimized way with SPV and fraud proofs, but we haven’t found it yet.

- Extending assurances to other chains (sidechain, security inheritance, merged mining). This model blesses other block space with Bitcoin’s security or extends Bitcoin’s own block space. Merged mined coins like Namecoin, proof-of-proof approaches like Veriblock, and sidechains like Rootstock are all roughly in the same family of approaches to the problem. These represent a compelling potential avenue to scaling, as they extend Bitcoin’s settlement guarantees to a potentially unbounded block space, but it is still under explored. However, assurance impairment is possible — risks remain that miners might censor sidechain closures or otherwise interfere with the sidechain. The productized implementations that we’ve seen like Liquid have used consortia rather than relying on PoW.

- Trust-minimized institutions. This approach takes the assurances of Bitcoin — natively auditable, scarce digital cash — and applies them in the context of a depository institution. In short, rather than individual users being the clients of Bitcoin, institutions like exchanges, banks, and custodians adopt the end user role, with their own users indirectly benefiting from Bitcoin’s assurances. Trade offs remain, and some features of Bitcoin don’t apply in a custodial context, but if protocols like Proof of Solvency are implemented, some of Bitcoin’s guarantees can shine through, even if filtered through an intermediary.

What should Bitcoin banks look like?

Is Hal’s vision of a world of banks backed by Bitcoin plausible? In one sense, it’s the world we have today, as many users only touch Bitcoin indirectly, through custodians and intermediaries. While most exchanges are presumed to be full-reserve, and indeed generally claim to be, in practice this isn’t universally the case. It’s becoming clear, for instance, that QuadrigaCX was running a fractional reserve for most of its existence. I don’t need to recap the sordid history of malfeasance and negligence at cryptocurrency exchanges.

Something as simple as a Proof of Solvency protocol would have made the Quadriga situation evident long before it folded. Rather, what would have happened in practice (imagine a world where solvency attestations were universal among exchanges) is that Quadriga would have refused to prove their reserves, and would have rightly come under suspicion, pre-emptively saving users a lot of heartache and lost coins.

Scaling the base layer. Rockport MA.

Scaling the base layer. Rockport MA.

An ideal Bitcoin bank would employ schemas like Proofs of Solvency to pass through Bitcoin’s assurances to depositors. Of course, these aren’t faultless, and can be cheated, but it’s a high bar to clear. You can lie to your auditors if you’re a publicly traded company, but you’ll likely be found out at some point, and now you’ve broken the law. Any serious Bitcoin bank engaging in an audit would likely only do so if they felt that they were going to pass it. As mentioned above, if this became popular, it would segment the Bitcoin depository industry into reputable, trusted banks which routinely proved reserves, and untrusted banks held in suspicion due to their unwillingness to provide these audits.

To be clear: I am not denying that IOUs circulating within and among banks generally fail to instantiate the properties of Bitcoin. What I am suggesting is a way to make those IOUs more Bitcoin-like, by providing depositors with certain assurances.

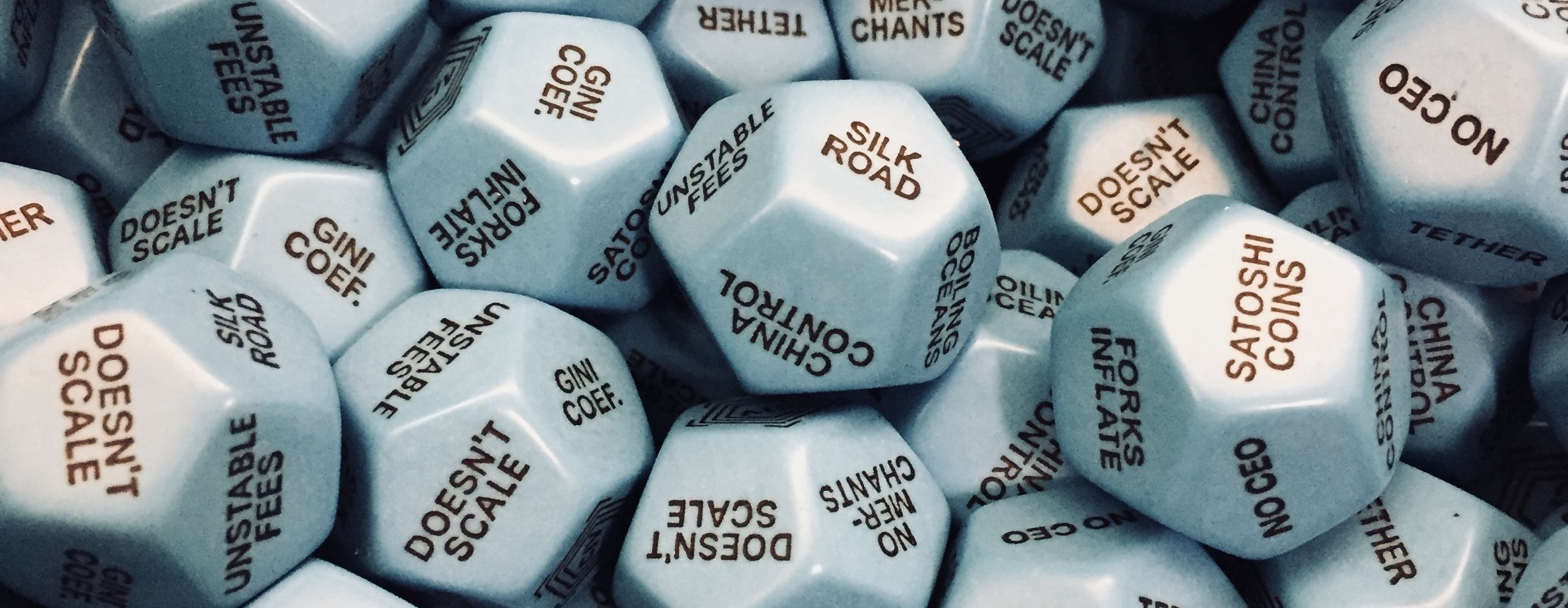

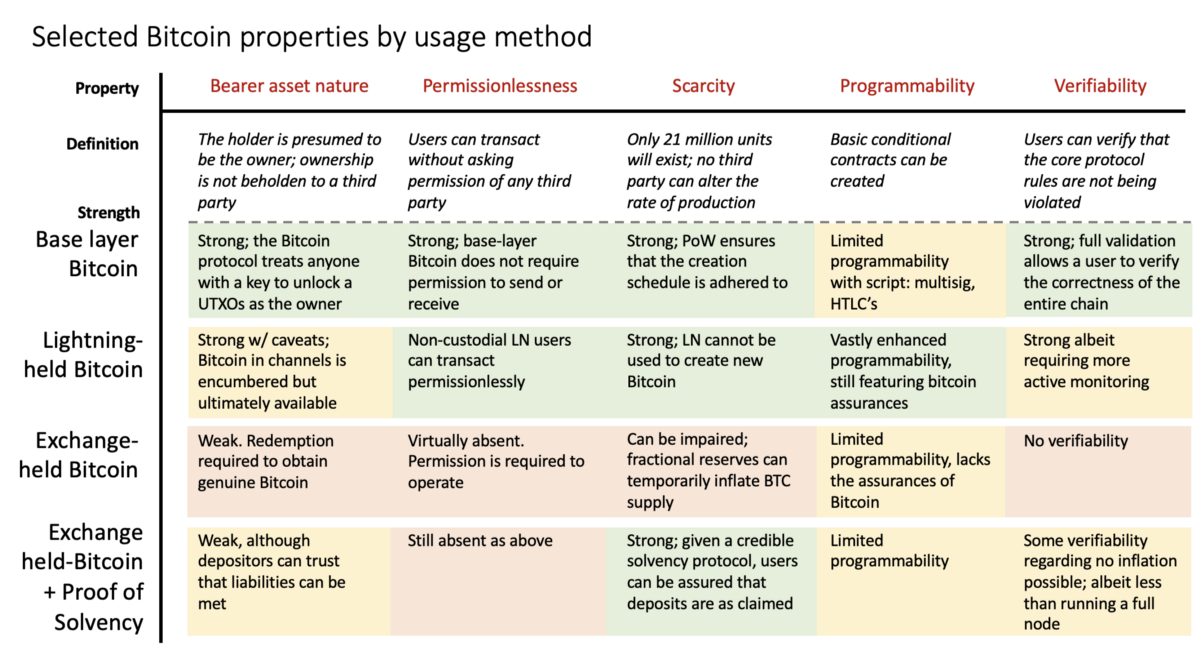

This table demonstrates that, while Lightning and other on- or near-chain layered approaches expand Bitcoin’s assurances to other domains, exchanges with proofs of solvency can chip in as well. Sidechains (if they ever get figured out) and Lightning are not mutually exclusive with the proposed institutional model: I envision them as parallel and complimentary approaches to scaling Bitcoin. The important thing to note is how little an IOU at a non-proof-of-reserve exchange means. It is very remote from base-layer Bitcoin.

Something else which is worth calling out: Lightning and other L2 approaches may well become mainstream approaches to scaling, but they do so under a different set of assurances. The assumptions that hold in Bitcoin are different in Lightning! There is nothing inherently wrong with this — and Lightning enthusiasts and developers will admit this — but they aren’t quite as ironclad as the settlement assurances that vanilla Bitcoin gives you. So the precedent that Bitcoin scales under various alternate tradeoffs is well-established, and should be generalized to institutions as well.

Credit creation on Bitcoin

Many Bitcoiners will recoil in horror at the words “fractional reserve,” even though they were uttered by Satoshi’s first disciple himself, Hal Finney. However, I believe that the risk of fractional reserves can be managed, if they are accountable to the free marketand if the banks are transparent about their actual reserves.

The problem with exchanges running fractional reserves is not, I’d argue, that they fail to operate at full reserve, but that they misrepresent their risk to depositors. While this is a heated debate among Austrian economists, I personally support a free market for user deposits, with exchanges running at various reserve or capital ratios.

The important thing is that they are transparent about it, so that users can adequately assess the risk of insolvency. As we well know, full reserves are not required for a bank to operate in practice, as users do not typically redeem all of their deposits at once. In the US, for instance, larger depository institutions must maintain a reserve equal to at least 10% of reservable liabilities. For a history of reserve requirements in the US, see this article by the Fed. I don’t know what the right number is in Bitcoinland, but I believe in the market’s ability to find that number. It’s evident by the popularity of lending facilities like BlockFi that some users will prefer interest-bearing accounts, and as such will tolerate some more risk at their bank.

Robust to external shocks: Bova’s bakery. Boston, MA.

Robust to external shocks: Bova’s bakery. Boston, MA.

What do proofs of solvency actually prove?

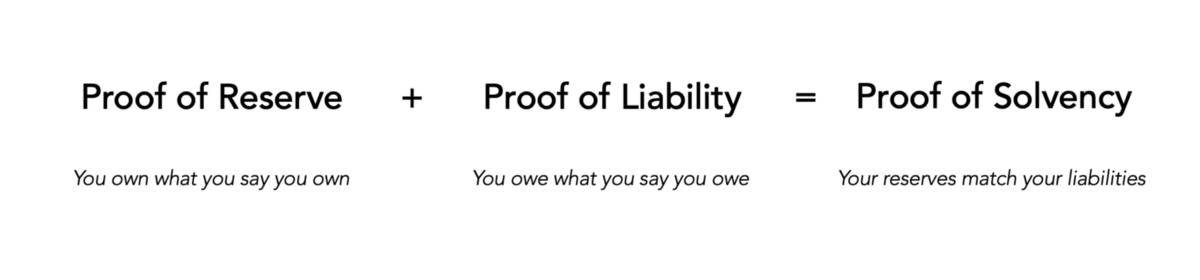

So far I’ve been treating proofs of solvency/reserve as largely homogenous, which does them a disservice. In fact, I should be more precise about the nomenclature. A proof of reserve involves proving what you actually own,and it is generally meaningless without a corresponding proof of liability, which is a proof of what you claim you owe. Together, if executed correctly, they can serve as a conditional proof of solvency.

The first method to prove solvency was formalized Greg Maxwell and Peter Todd, which we’ll call the Merkle approach.Presented at length here by Zak Wilcox, the Merkle approach allows users of the exchange to verify that their balance is included in the list of all customer balances that the exchange publishes in their attestation. There are two parts to the process, proving what you owe, and demonstrating what you own. As described by Greg Maxwell:

<@gmaxwell> First you show how much funds you have via signmessage for actual coins on the chain. Thats easy enough.

Then you need to prove how much you should have. This is a little tricker. You could just publish EVERYONE's balances e.g. by account ID but thats undesirable for privacy and commercial reasons.

Proving reserves is actually the easy part — the exchange signs a transaction with all of their UTXOs. Everyone can now see that the exchange owns x BTC. Of course, the exchange can borrow Bitcoins for this. This is why the attestation only works on an ongoing basis, and should be paired with an analysis of cash flows (imagine an exchange that habitually borrowed 10,000 BTC every quarter, the week before their solvency attestation, and paid it back the next day!)

The challenging part is proving what you owe — that is, what your liabilities are to depositors. This is where the Merkle tree comes in — it allows users to verify that their accounts and balances are included in the final hash without leaking the details of everyone’s balances and account information. Like herd immunity, users can have relatively strong assurances that the exchange is not lying if a sufficient number of them verify their balance.

A malicious exchange can of course cheat by publishing 0 balances for dormant accounts that they expect not to perform the check; but they run a big risk in doing this — if even one of the zeroed accounts makes the check, the exchange is exposed.

As Zak says, the Merkle approach

[…] gives you the means to check your own belief of the exchange’s liability/obligation to you is included in their publicly declared one, and to let you make an informed decision about whether to continue doing business with them if those numbers differ.

Steven Roose of Blockstream has formalized the proof of reserve portion of the process with a BIP and a Github implementation. This should be paired either with the proof of liabilities (as described above) or a credible auditor.

The problem with the Merkle approach is that it makes public the exchange’s liability, which many exchanges may not want to do. Thus in 2015 Dagher, Bunz, Bonneau, Clark and Boneh published Provisions: Privacy-preserving proofs of solvency for Bitcoin exchanges . Addressing the shortcomings in the Merkle approach, Dagher et al set out in Provisions to:

[E]nable an exchange E to publicly prove that it owns enough bitcoin to cover all its customers’ balances such that (1) all customer accounts remain fully confidential, (2) no account contains a negative balance, (3) the exchange does not reveal its total liabilities or total assets, and (4) the exchange does not reveal its Bitcoin addresses.

Provisions consists of three protocols:

- Proof of assets (/reserves): the exchange uses some ZKP trickery to prove that it owns a certain number of BTC, without revealing that number (read the paper for more detail)

- Proof of liability: the exchange commits to the total sum of user balances, also allowing depositors to privately verify that the exchange is committing to the right balance

- Proof of solvency: the exchange proves in zero knowledge that the proof of assets and liability sum to 0

This is an improvement over the Merkle + signmessage approach, as it doesn’t leak the exchange’s balance, instead outputting a simple 1 or 0 — the exchange is solvent or not.

Other work on the topic that I wont summarize includes:

- Decker, Guthrie, Seidel, Wattenhofer (2015),Making Bitcoin Exchanges Transparent

- Mohan and Devi (2017),Privacy Preserving Non-interactive Proof of Assets for Bitcoin Exchanges

- Narula, Vasquez, Virza (2018),zkLedger: Privacy-Preserving Auditing for Distributed Ledgers

In short, between the Merkle approach, and the various ZKP approaches that have been proposed, copious tools exist to enable Bitcoin banks to prove their solvency. Today, they have little reason not to.

Where are the Bitcoin banks?

So if Finney’s Bitcoin banks can help scale Bitcoin, where are they? The large exchanges and custodians (I’m using exchanges, custodians, and other depository institutions that take Bitcoins interchangeably with ‘banks’ here) are just another set of trusted third parties. As the gatekeepers to Bitcoin, they often do more harm than good, impairing open access and free exit.

Ok, so the title was a slight exaggeration. Coinbase-BTC-IOUs and Bitfinex-BTC-IOUs and Xapo-BTC-IOUs don’t grant users the same transactional assurances as raw, commodity Bitcoin, but they still represent an under-appreciated scaling vector. Those who have professed their belief in institutional scaling include Xapo CEO, Wences Casares:

We have a lot of transactions that happen within Xapo. Because the Xapo to Xapo transactions don’t need to go through the blockchain so they don’t. They can happen in real time and for free. So today we see about 20 Xapo to Xapo transactions for every transaction that we run through the blockchain.

It’s easy to see how a bitcoin bank could issue actual notes against deposits, serving as the pegs in a sidechain. For it to be credible though, you need redeemability. This is the same issue that Tether faced — for a time, no one believed that they could actually redeem USDT. Ongoing attestations to reserves would help with this.

As stated, a proof of reserve audit allows a depository institution to prove that they hold a certain amount in reserve, which would then — with the help of a trusted auditor — be used to demonstrate that their liabilities matched their reserves.

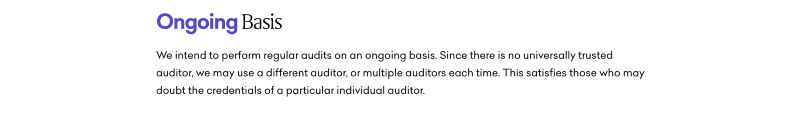

Alternatively, you can let users determine that internal balances exist to match their own deposits; if enough users do this, you can have reasonably strong assurances that the exchange is solvent. It should be noted that proofs of reserves are by no means a silver bullet. Coindesk’s Danny Bradbury notes that both Bitcoin reserves and fiat operations should be proven, and that snapshots are far inferior to an ongoing reserve proof.

Historically, many exchanges have conducted proofs of reserves. These appear to have mostly been catalyzed by the Mt Gox insolvency. Interestingly, the history of proofs of reserves is mostly one of broken promises. Several exchanges have deleted any trace of their previous proof of reserves attestations and others have backtracked on promises to perform proofs of reserves on an ongoing basis.

- June 2011: Mark Karpeles constructs a crude proof of solvency with the famous 424,242 BTC transaction

- February 2014: Coinkite posts a now-deleted proof of reserve audit

- February 2014: in the wake of the Gox insolvency, executives at Coinbase, Kraken, Bitstamp, BTC China, Blockchain.info, and Circle publish a joint statement promising audits and more transparency. Only Kraken and Bitstamp prove reserves, and none on an ongoing basis

- February 2014: Coinbase summons Andreas Antonopoulos to review their storage practices, although he does not conduct a formal review. He subsequently deletes his blog about it

- March 2014: Bitstamp publishes an outside attestation as to their solvency, in the process creating the largest transaction in history (at the time)

- March 2014: Kraken proves reserves using the merkle approach,claiming that they “intend to perform regular audits on an ongoing basis.” They do not.

- April 2014: British exchange Coinfloor issues their first provable solvency report. Unlike every other Bitcoin exchange in existence, they follow it up with another report the following next month. And again. And again. Last month, they published their 60th report, far more than every other exchange combined.

- August 2014: Stefan Thomas announces that he has completed a successful proof of reserve audit for OKCoin. However, in a now-deleted reddit post, the outgoing OKCoin CTO subsequently claims that OKCoin misled Thomas and partially faked the audit. A CCN article entitled “OKCoin passes proof of reserve audit” is also later deleted

I can confirm OKCoin removed a number of accounts (used by OKCoin bots) to pass the Proof-of-Reserve audit in Aug 2014. In essence, these bots trade on fractional (or fictional) reserves. Stephan Thomas was lied to during the audit. This is an unfortunate limitation of the proof-of-reserves method.

- August 2014: Huobi releases a proof of reserve audit administered by Stefan Thomas

- June 2015: Bitfinex issues a press release stating that, using Bitgo’s multisig software, they will rid themselves of their omnibus model and store user coins in segregated accounts, so that depositors could verify their holdings on-chain in real time. In August 2016, Bitfinex is hacked to the tune of of 119k BTC and they abandon the segregated multisig method. Bitfinex subsequently publishes BTC, EOS, and ETH coldwallet addresses for public scrutiny

- November 2018: Tether issues a quasi-proof of reserves; their banking partner Deltec Bank and Trust Limited attests to their cash balance. This matches the amount of Tethers in circulation, although skeptics aren’t quite satisfied

Waiting for exchanges to follow up on initial proofs of reserves

Waiting for exchanges to follow up on initial proofs of reserves

One commonality emerges: exchanges and depository institutions tend only to issue attestations or proofs of reserve under extreme duress. The flurry of activity in 2014 was precipitated by the Gox insolvency. Despite claims that proofs of reserves would become enduring and routine processes at these exchanges, not one has honored that promise aside from Coinfloor.

Perhaps things are changing. New depository institutions like Fidelity Digital Assets, Square Crypto, Bakkt, and ErisX are entering the market, several of which have announced their intention to be more accountable to Bitcoin users. As regulators become more sophisticated, it doesn’t seem inconceivable that they might one day expect cryptographic audits from Bitcoin banks. Now that QuadrigaCX is being exposed as not an accidental key loss but an actual insolvency and potential fraud, 2019 might be an opportune time for some of these exchanges to revisit their proof of reserve protocols. If they don’t, the new breed may well eat their lunch.

Conclusion

Bitcoin is an institutional technology, a nation state without an army. Perhaps instead of trying to force it into a mold that ill-suits it, we should instead try to reckon with its present reality. Yes, a messy patchwork of custodians and banks has emerged, many of them taking a devil-may-care attitude to user deposits. Over a billion dollars have been stolen or misappropriated from these honeypots.

How, realistically, can this state of affairs be amended to suit Bitcoin’s nature? Despite a refrain of “not your keys, not your coins,” the Bitcoin banks are here to stay: the convenience tradeoff is simply too compelling. What if we acknowledge that they will persist as long as they perform a useful service, and focus instead of bringing Bitcoin’s assurances to them?

Ten years on, Bitcoin has entered its adolescence. Perhaps by seeing it for what it is — a peculiar beast, suitable for a narrow set of things — it can become more comfortable in its own skin. By adding institutions to the set of entities accountable to Bitcoin’s innate transparency, we can radically improve the state of affairs in Bitcoin’s depository industry today.

Objections

Bitcoin Banks are inherently incompatible with Bitcoin

There is a somewhat nihilistic view present in Bitcoinland which starkly denies the importance of exchanges and custodians, as if they didn’t exist. This is often born, in my opinion, of a nostalgia for the 2010–12 era when the network was genuinely quite flat and non-hierarchical. Of course, you can’t inhibit free enterprise and commerce, and smart entrepreneurs decided to create useful services of exchange, custody, and banking for bitcoiners.

Far from being a dark irony, as most pundits maintain, I think this is a perfectly natural evolution. Banks are now a meaningful portion of our network, and we have to live with that. Yes, running a node to verify incoming payments matters, but factually, some nodes matter more than others. In particular, exchange nodes, the nodes powering block explorers, blockchain API companies, merchant services, and one day, big lightning hubs. There’s nothing wrong with this, and it doesn’t compromise Bitcoin.

It is fashionable to declare not your keys, not your bitcoin, and while absolutely true, this also misses the point. What do we do about the people that have decided to surrender their keys in exchange for IOUs at a bank? Do we smugly deride them for being unwilling to self-custody (still not intuitive for most normal people)? Or do we empathize with them, and try and ameliorate their situation by holding exchanges accountable? I strongly suggest we do the latter .

Why would anyone start proving reserves now, given that it’s so out of favor?

There is a perverse feature of the cryptocurrency industry that could be referred to as the paradox of transparency. Put simply, the more transparent you are, the more attack surface you open up, and the more opportunity your critics have to undermine you. As a consequence, being open and transparent is disincentivized. Since this industry has been lightly regulated so far, most successful projects are highly obscure in their operation. There is no equivalent of a 10-K for established projects or an S1 for new token launches.

The same goes for Bitcoin depository institutions: they are regulated under a vague patchwork of regimes with no domain-specific regulation in place (in the US at least). Against this backdrop, it is often advantageous to them to disclose as little as possible about their operations. Additionally, proofs of reserves are costly; and in the lasts three years exchanges have not sought to differentiate themselves on credibility but rather liquidity and number of listings.

I believe that there are several catalysts for exchanges to start proving reserves:

- The growth of SROs. Absent any new legislation or more activist regulators, self-regulatory organizations may come to play a larger role in the US and other developed nations. Japan leads the way already. SROs will need to advocate to their national governments that they are imposing standards on exchanges, and asking member organizations to prove solvency is an easy (and not overly onerous) carrot.

- The extended fallout from QuadrigaCX. The full details from the scandal have not yet been revealed, but it is increasingly likely that it was not a case of misplaced keys. Forensic evidence is pointing to a deliberate, years-long fractional reserve. This kind of deception is unprecedented in Bitcoin; in Gox, the exchange was hacked rather than deliberately stealing funds from depositors.

- A bifurcation into grey/black market and compliant exchanges. A split is coming where a set of sophisticated, regulator-friendly exchanges emerge make a clean break from the underclass of unregulated exchanges.This new cohort will seek to differentiate themselves, not on the basis of the number of tokens traded, but in terms of credibility and security. Introducing audits which include proofs of reserve will be a natural source of differentiation.

Fractional reserves at banks permanently destroy the value proposition of Bitcoin

There is a common misconception that a Bitcoin bank running a fractional reserve permanently impairs Bitcoin’s assurances. For sure, a fractional reserve at a bank inflates the supply of credit (loosely, money) for the period that it persists. QuadrigaCX did exactly this: they didn’t have sufficient reserves, and they covertly increased the supply of Bitcoin, if you include Bitcoin IOUs in your assessment of Bitcoin’s supply.

However, covert fractional reserves are unsustainable — they typically get found out, as happened with Gox, and Quadriga, etc. When this happens, the Bitcoin credit supply shrinks as the fraud is uncovered and those IOUs lose their convertability. Fractional reserves are leveraging, and their discovery is a deleveraging. So the covert inflation of the money supply only occurs while that covert fractional reserve is running. The largest banks — Coinbase, Bitfinex, etc — have a strong incentive not to misrepresent their solvency, because they have reputations to uphold, and executives face jail time if they do. And as this industry matures and more regulated banks come to account for a larger fraction of the market, most funds under custody will settle with the most responsible banks.

Fractional reserves are inherently bad/evil

This is more of a philosophical position than one that can be settled empirically. I happen to believe that non-full-reserve banking on Bitcoin is inevitable, and since it is inevitable, we might as well advocate for it to be as responsible and transparent as possible. I believe that the reason fractional reserves at Bitcoin banks are bad is not due to any inherent problem with fractional reserves themselves because they misrepresent the solvency of an exchange. Full reserve exchanges can always redeem deposits; fractional reserve exchanges occasionally default on that obligation.

If I lend my friend Bitcoin for a month, I have created credit. Genesis, BlockFi, and Unchained Capital all do this, but on a bigger scale. Institutional prime brokerage — the same concept, but on a much larger scale — is just around the corner. When a bank runs a fractional reserve, they are doing the same thing. They create credit by lending out a portion of user deposits and they make money by charging a higher rate on those loans than the interest that they pay depositors. So for fractional reserve skeptics to be consistent, they have to be against all lending activity relating to Bitcoin. I have actually seen this view expressed, but it seems extremely draconian — and unrealistic to boot. There is a clear demand to borrow and lend Bitcoin.

I take a similar attitude to fractional reserves as I do to the existence of custodians: they are inevitable, so we might as well make them as transparent as possible. I propose exposing Bitcoin banks to the same forces that gave rise to Bitcoin itself: the free market. Right now we have a market for custody which everyone naively believes is fair, and is periodically beset by shocks as fraud is exposed. Why not a market for custody where the varying reserve ratios on offer are made transparent?

It’s impossible to effectively audit a Bitcoin bank

One of the harshest critics of the reserve currency model of Bitcoin is Eric Voskuil. In a post on his Libbitcoin wiki, Eric pushes back at the Ammousian view of Bitcoin as a sound reserve to be used by commercial or central banks, similar to the way our monetary system used to operate with gold. (Eric also gave an interesting talk on the topic at Baltic Honeybadger 2018).

Eric dismisses the notion that paper certificates against depository Bitcoin are credible, stating:

The ratio of issued [Bitcoin IOUs] to BTC in reserve cannot ever be effectively audited.

It seems that Eric’s critique relies on a few beliefs:

- That commercial banks would be coopted by the State — indeed, that banks are mere extensions of the State

- That proofs of reserves can never provide adequate guarantees to depositors

- That reserve ratios must be upheld by trust and hence would fail to be enforced

- That the entire bitcoin market would be consolidated within these depository institutions would would settle IOUs against each other

I don’t have the space to give them a full treatment here; I would defer to Juice’s excellent point-by-point rebuttal. To be frank, I just flat out disagree with Eric on a few key areas here. I think that proofs of reserves, if done correctly and with a reputable auditor, can provide depositors assurances of solvency in spades. I also don’t believe that the government would immediately come to control the entire money supply in a bitcoin depository setting; commercial banks are independent, and in a non fascist state, would remain so.

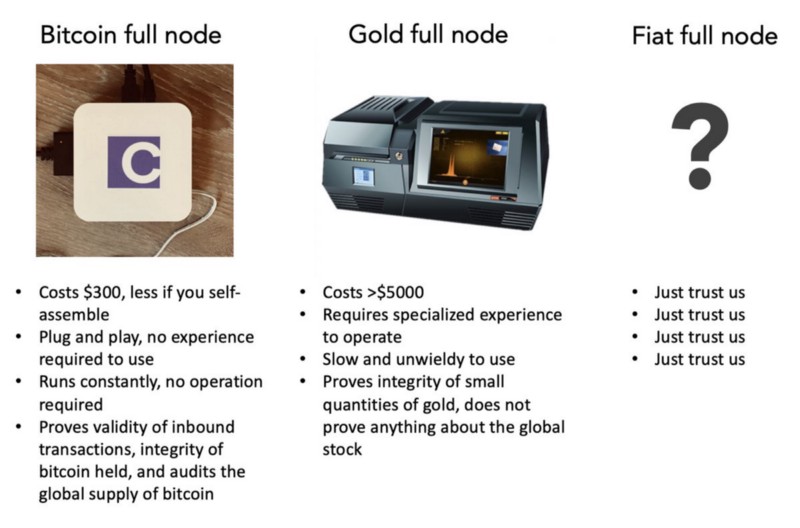

Let’s rewind a bit. To believe that a Bitcoin banking system can escape the problems that doomed the gold-based system, you have to believe that there are advantages that Bitcoin has relative to gold as a reserve asset. I would venture that it is the case. In particular:

- Bitcoin is auditable by design. What an individual does when they run a full node is that not only do they continuously audit the supply and make sure that the rules are being followed, but they audit the entire sequence of historical transactions to make sure every single one was legitimate and within the rules

- Auditing Bitcoin’s M1 is cheap. It costs a few dollars a month to run a node. Gold nodes, by contrast, are expensive. XRF Spectrometers are pricey and tricky to operate. A fully trusted gold supply chain is so expensive that there only a handful in the world, with London being by far the biggest. In practice, in the private gold market, the cost of verifying any given lump of gold is so high that entire trusted supply chains have been created, so that gold circulates within a walled garden and doesn’t have to be reverified at every step. If you are curious, read the LBMA’s good delivery rules. $300b worth of gold is currently held in London within this framework. Alternatively, central banks just custody large quantities of gold themselves and never move it.

- Assessing the amount of Bitcoin credit outstanding is at least plausible, whereas for gold it’s impossible. If exchanges issue IOUs redeemable for Bitcoin deposits, as they do today, we have the tools to verify that they aren’t lying to us

In short, Bitcoin provides auditability guarantees that are incomparably better than those provided by gold, doing away with the need for a trusted supply chain, costly overhead for storage, or costly inbound verification. The cryptographic nature of Bitcoin, which can be extended through simple proof of reserve attestations, is exactly what makes it so amenable to trust-minimized custodianship.

Why are you settling for intermediation? Why not push for a world where Bitcoin is used directly by all?

I’m aware that my approach could be perceived as settling. However, I think the opportunity to live in a world where non-intermediated Bitcoin is the sole mode of usage has long passed us by. Normal people have a voracious demand for custodians and banks — and that makes sense. We don’t self-custody our stock certificates either. These things are a challenge to custody ourselves, and the additional benefits of banks — earning interest, providing peace of mind, and so on — have made them extremely popular.

According to Coinshares, about 2.9m BTC are currently held in the custody of entities like Coinbase, Xapo, the Greyscale Bitcoin trust, Binance, and so on. Coin Metrics tells us that about 14 million Bitcoin have been active in the last 5 years (total issued supply is 17.6m, but significant portions of supply are lost or inert), so that leaves us with 20 percent of the effective bitcoin supplyin the hands of third parties!

Slide from my presentation at BH2018

Slide from my presentation at BH2018

I don’t happen to believe that we will all collectively wake up one day and decide to self-custody. I see this industry going two directions: one where custodians continue to breach our trust and lose user deposits, or one where we hold them accountable to a high standard. For the latter to occur we need to acknowledge that they are an important part of the Bitcoin economy, for better or for worse. If the existence of intermediation implies that Bitcoin has failed, then the dogmatists should abandon the project.

And, to be frank, even if you don’t like the idea of Bitcoin banks, you have nothing to lose from demanding that they prove their reserves. Normal financial institutions deal with stringent regulations because the consequences for failure are so severe. In lieu of a regulatory regime covering institutions which take Bitcoin deposits, we might as well lobby exchanges to audit themselves.

What if [bad thing] happens to Bitcoin? Is this generalizable?

The framework I’m proposing applies to any auditable digital bearer asset. That’s the distinction between gold and virtual currencies/commodities: they are natively auditable, whereas gold is extremely cumbersome to audit and verify. Privacycoins are more challenging but there are ways to audit them with viewkeys or selective disclosure.

Lending by Bitcoin banks effectively inflates the supply of BTC

Canny readers will remember their Econ 101 classes where it was demonstrated that the cascade of deposits and lending at banks with low reserve ratios leads to the effective creation of new money — far more money than existed in deposits.

This would be the case if a vibrant industry of non-full-reserve Bitcoin banks were to appear. In fact, if you squint a bit, this reality is the case today. Nominal volumes on the Bitcoin derivatives exchange Bitmex eclipse those at spot exchanges. Far more Bitcoins trade there than exist in deposits at the exchange, precisely because Bitmex extends loans to users in the form of margin. That’s credit creation.

I don’t think there is anything inherently wrong with the creation of credit, as it is the most basic component to finance. If credit is being created in a transparent way, on top of a reserve asset that is no one else’s liability, that’s a significant improvement over our current system. And I think it’s something worth pursuing.

Thanks to Hasu , Matt Walsh, and Warren Togami for their feedback and assistance with this article.