Five Fundamental Effects in Bitcoin

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

Five Fundamental Effects in Bitcoin

Cobweb Supply, Reservation Demand & the Foundations for Understanding Bitcoin’s Price

By Prateek Goorha

Posted May 19, 2019

Bitcoin. An actual diagram.

Bitcoin. An actual diagram.

Bitcoin’s value has little to do with its quotidian price histrionics. Yes, exuberant speculation routinely outplays rationality. And, of course, there are complex interactions from extant and expected financial market innovations, growing or abating regulatory risks, and the insidious exertions of misinformation.

But price is important. To say you are interested in Bitcoin, but far too cerebral to care about its price is as daft as saying that you are interested in gold, but only as an element on the periodic table.

That said, I fear that you learn nothing of value about Bitcoin from looking at charts and following the mood swings of ‘traders’ on Twitter (especially about its price!). What you need to understand price is a deeper understanding of the effects that are unique to Bitcoin and how they come together in a market in interesting ways.

Therefore, in this piece I wish to give you a simple demand and supply model that has helped my thinking about Bitcoin, and it continually helps me absorb the insights of others. And, to make the model real for Bitcoin, I will also enumerate five of the most basic effects that are important to Bitcoin’s price.

Together, the model and the Five Effects, will, I sincerely hope, help you appreciate the splendor of the forest rather than be distracted by its weirdest trees.

Supply and Demand Redux

Let’s start with the demand and supply model. The Five Effects we will examine below are each part and parcel of an overarching market dynamic that the model helps bring together.

Simply put, the model shows how Bitcoin’s market price emerges from the ideas of a cobweb supply and a reservation demand.

The cobweb model, developed in the 1930s, favors the supply-side in its construction. Essentially, it relies on decisions made by firms on production volumes reacting to extant market prices with a lag between current market supply and future market supply. Suppliers produce based on extant resource costs and permit the ramifications of these ex ante provisioning decisions to play out in the market with a delay, ex post.

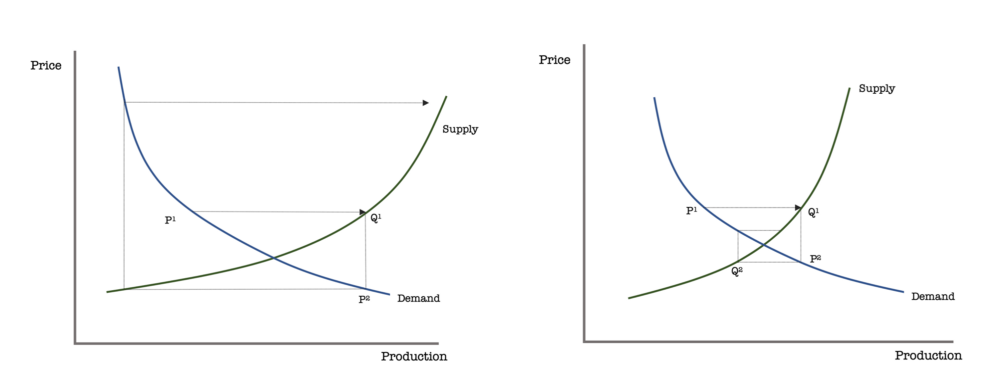

At a given price, say P1, suppliers plan production at a level of Q1 in advance. Later, when the produce is sold, the price may be pushed down to P2 by virtue of a market glut. This lower price then inspires a lower level of planned production among suppliers. This time the market pushes the price upwards by virtue of a shortage.

This feedback loop of lagged responses creates a ‘cobweb effect’ on the demand and supply diagram, as shown in the figure below. Two cobweb patterns are possible: Depending on the relative elasticities of supply and demand the spiral can lead to an explosive price dynamic further and further away from an equilibrium price, or it may cause the market to converge toward the equilibrium price.

Cobweb Supply. The left panel shows a divergent price dynamic: When supply is more elastic than demand, market price is pulled farther away from an equilibrium (a divergent cobweb). The right panel shows a convergent price dynamic: When supply is less elastic than demand, market equilibrium becomes more attractive (a convergent cobweb).

Cobweb Supply. The left panel shows a divergent price dynamic: When supply is more elastic than demand, market price is pulled farther away from an equilibrium (a divergent cobweb). The right panel shows a convergent price dynamic: When supply is less elastic than demand, market equilibrium becomes more attractive (a convergent cobweb).

There are several important aspects of the cobweb model that can be challenged, and the most critical among these is that of learning by producers. Indeed, it seems reasonable to argue that, when producers adapt their expectations of future market prices, the oscillations in the cobweb supply ought to be more muted. While this may have been the reason for the model falling out of favor in economics, the cobweb model is full of insight for the case of Bitcoin for very sound reasons.

When a particular market price is expected, miners in Bitcoin have the option to increase their stocks in order to dampen the effect of a divergent cobweb. For miners this ability directly depends on the block rewards progressively contracting at each halving event and the average costs of production progressively rising. The effect of both these aspects is that supply elasticity progressively diminishes, albeit conditioned by the stock that miners, large retailers and ‘HODLers’ with a long-term commitment to Bitcoin can maintain. As Bitcoin matures, the fluctuations become less pronounced between a divergent and a convergent cobweb.

Key to the above is understanding the role of demand. More than just the relative elasticity of demand, what also matters are the shifts in demand. Adverse impacts to demand (that cause it to shift leftwards) exacerbate the divergent cobweb’s explosive nature, and place an even greater burden on the ability of suppliers to hold stock as inventory.

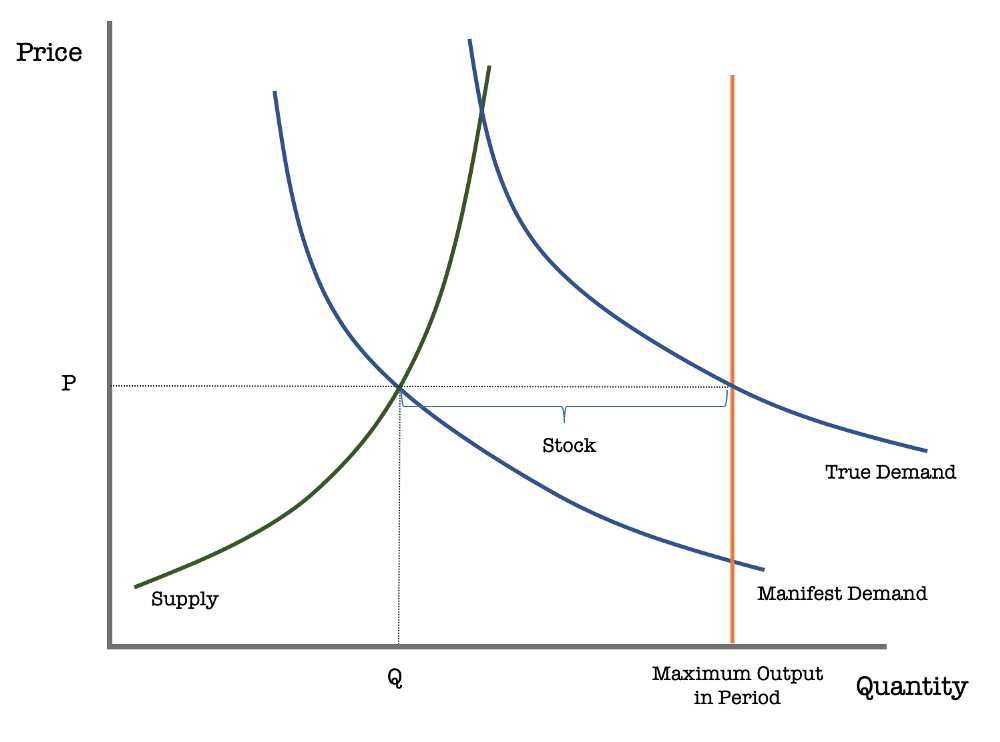

The demand-supply diagram we have drawn above depicts the usual ‘Marshallian’ market that is familiar to any student who has studied elementary economics. However, demand curves like these tend to gloss over the assumption that they are aggregating over different kinds of consumers; specifically, firms who have a reservation demand for their own good so that they may add to their stock.

The rationale for why firms can have a reservation demand for their own produce is partially already clear from the cobweb supply model. Suppliers often face contextually strong production conditions that can force them to plan production levels well in advance of sales and then require them to maintain a stock of their output.

Expected increases in resource costs or uncertain regulatory changes; the threat of technological breakthroughs; periodicity in market interest, and a host of other factors can motivate a distinct reservation demand for producers that is different to the demand for the good that its consumers may have.

To such contextual conditions, Bitcoin also adds structural parameters in the form of a difficulty that adjusts to coordinate the competitive efforts and resource commitments that miners must undertake. And, of course, the prospect of halving events that force the supply curve to become increasingly inelastic.

Reservation Demand. True demand represents the manifest consumer demand plus the reservation demand from suppliers for the stock that is produced for the period, which is capped in advance.

Reservation Demand. True demand represents the manifest consumer demand plus the reservation demand from suppliers for the stock that is produced for the period, which is capped in advance.

So, the above is a quick sketch of the demand-supply model that I think is useful to have in mind when understanding how the latest news story or development will impact the demand and supply. Now, to fill in the details for this model with some hard data from Bitcoin let us examine the five key factors.

The Five Effects

The five foundational aspects for Bitcoin are:

- The Limited Supply Effect

- The Market Vibrancy Effect

- The Competitive Effort Effect

- The Resource Constraint Effect

- The Structure Parameterizing Effect

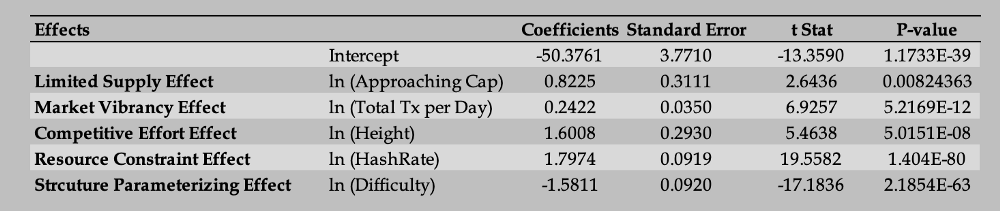

We shall now consider each effect, in turn, by considering a proxy variable that we can use to develop an overall statistical model. The results of this regression analysis are presented in the final section.

It is important to understand that the effects all matter to Bitcoin, and so any bivariate model that only picks any one of the effects and examined its effect on Bitcoin’s is likely incomplete. With this in mind, I have stated the partial influence that each of the five effects exert on Bitcoin’s price in the sections that follow.

The data are drawn daily, covering the period July 17, 2010 to May 14, 2019, constituting 3224 observations for the overall regression model.

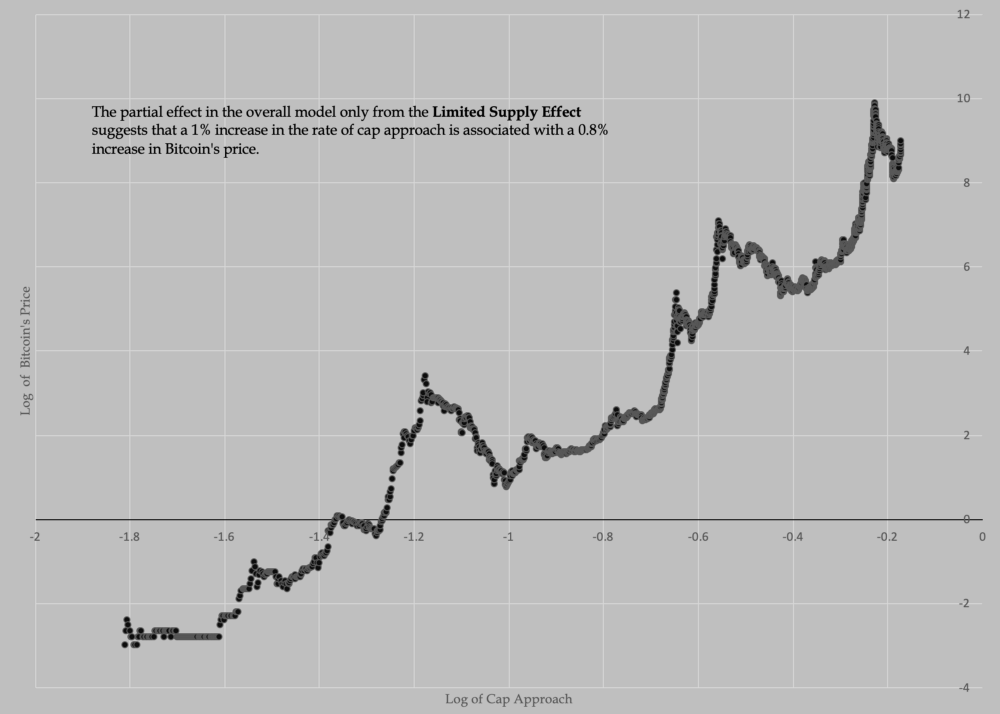

1. The Limited Supply Effect

Limited supply is the bedrock of Bitcoin. It is also crucial to seeing why cobweb supply and reservation demand are the right tools to understanding Bitcoin as an economic market.

Here, I have proxied the limited supply effect with a variable I have called cap approach. The idea is that an approaching cap on the amount of production exerts itself on the production plans for miners. A strongly convex supply curve is common knowledge among miners and the cap approach rate makes it increasingly vivid to market participants over time.

The figure below plots price against the cap approach to give a sense of how they relate. The inset text shows the size of the effect from Limited Supply Effect in the context of the broader model conditioned by all five effects simultaneously.

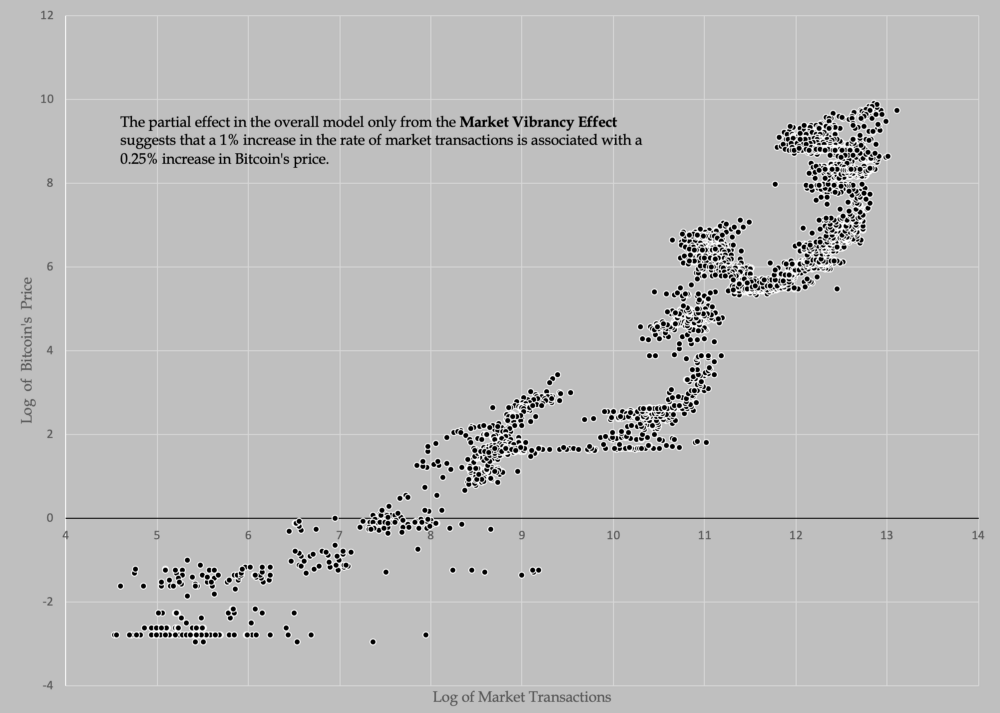

2. The Market Vibrancy Effect

Any market model’s usefulness is mediated by the vibrancy of the market. The cobweb supply and reservation demand model is no different; without a robust level of transactions in the market the relative position of manifest demand compared to true demand becomes much harder to establish. This, in turn, makes gyrations in the cobweb model between convergence and divergence more unpredictable.

The figure below uses the number of market transactions as a proxy variable for the Market Vibrancy Effect.

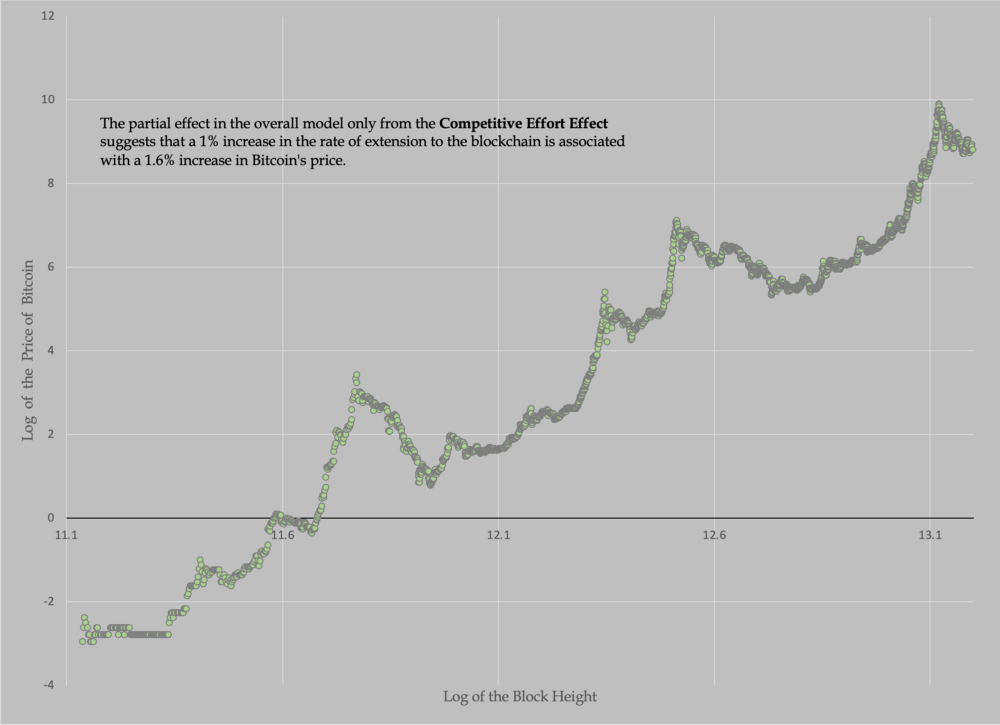

3. The Competitive Effort Effect

The incentive to increase reservation demand depends on the manifest market demand, but it also has a direct relation to the competitive efforts of rival producers. In Bitcoin, miners can gauge the level of such competitive efforts through multiple publicly visible variables. Block height is perhaps not the only proxy variable that one might use for this purpose, but it does make a great deal of sense to do so. Block height is sufficiently separated from price and the rate at which it alters is far more closely linked with the competitive efforts expended across all miners.

The figure below presents the results and states the partial effect of the competitive effort effect on Bitcoin’s price.

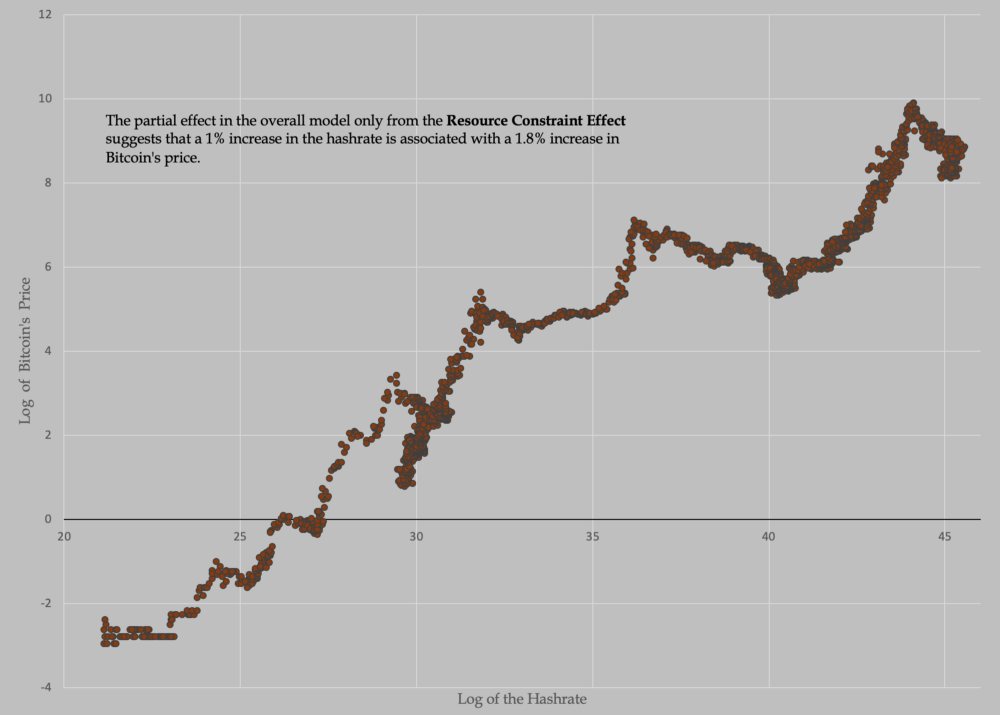

4. The Resource Constraint Effect

Resource constraints are essential to the idea of what inspires producers to provision supply ahead of realized demand. The stronger the influence of the opportunity costs of resources deployed for production, the more likely it becomes for producers to plan production, hold stocks and impact market price through the rate at which they sell their stocks. The hashrate stands as a strong candidate for a proxy variable for this effect. The figure below presents the result and states the partial effect of hashrates on Bitcoin’s price within the overall model.

5. The Structure Parameterizing Effect

The final effect is my firm favorite for the simple reason that it forces us to contend with a rude fact: The rules of the game for Bitcoin are fundamentally different from the other economic markets we have learned to caricaturize with the aid of demand and supply diagrams taught at school.

The structure for the overall Bitcoin market is represented with an algorithmic mechanism that governs its functioning. The word ‘govern’ is anathema to why I admire Bitcoin, but it is also the right word in this context. If market participants can adjust their strategies in such a manner that the market can be subverted into operating differently from its idealized conception, it isn’t parameterized in any meaningful way. Bitcoin is parameterized, and there is arguably no better proxy variable for this than the difficulty adjustment variable. It is because of the difficulty adjustments that miners alter their production plans; because of it that the feedback loop of a cobweb model does not spiral out of bounds with invidiously explosive overproduction or throttling underproduction.

The overall regression model, with all Five Effects, is presented below. That the coefficients are all highly significant and that the overall model specification is also highly significant with an R-Squared that exceeds 97% is less relevant. There are a host of statistical issues that need resolving, but which are beyond the scope of this informal piece. However, it does make the message clear:

Bitcoin’s value comes from an understanding of demand and supply that is uncomfortably new to most (especially to most economists!). And, much of this intrinsic value rests on the firm foundations provided by just five effects.

Further reading

- Holland, Thomas E. “Marshall, Walras and the Cobweb Theorem.” The American Economist 21, no. 2 (1977): 23–29.

- Ezekiel, Mordecai. “The Cobweb Theorem.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 52, no. 2 (1938): 255–80.

- Coase, R. H., and R. F. Fowler. “The Pig-Cycle: A Rejoinder.” Economica, New Series, 2, no. 8 (1935): 423–2