Breaking Down the Bitcoin Lightning Network: eltoo

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

Breaking Down the Bitcoin Lightning Network: eltoo

By Brandon Arvanaghi

Posted July 25, 2019

The Lightning Network is a Layer 2 solution that allows you to create micropayment channels with other Bitcoiners. It allows instant and trustless peer-to-peer transacting while limiting the amount of data needed on-chain.

In this post, I break down exactly how it works, as well as a newly proposed update protocol within it called eltoo (named after L2).

Unidirectional Channels

Unidirectional payment channels are the simplest to implement in the Lightning Network because money only flows in one direction. The most common use case is streaming money; for example, a micropayment for each minute of a video you watch.

Say you want to start such a channel with Netflix. First, you create a funding transaction, which is you locking up a certain amount of your money that you are willing to pay to Netflix (but have not yet paid them).

Say you fund this transaction with 10 Bitcoin and publish it on the Bitcoin blockchain. After being mined, this funding transaction can be spent by a 2-of-2 multisig consisting of your’s and Netflix’s keys.

As Netflix starts streaming you bytes of video, you start streaming them money — say .000001 Bitcoin per minute of video — via partially signed transactions that spend this funding transaction.

Using the funding transaction as input, you create two new outputs: one sending .000001 to Netflix, and the other 9.999999 to you. You sign this transaction and share it with Netflix off-chain (that is, without attempting to publish it to the Bitcoin blockchain). This transaction is considered “partially signed” because it only contains one of the two signatures necessary to spend.

When Netflix receives this partially-signed transaction, they are in control. Netflix can choose to claim that .000001 Bitcoin immediately, and in the process send the remaining 9.999999 Bitcoin back to you, by adding their signature to the partially signed transaction and publishing it. This is considered closing the channel or a settlement.

Instead, Netflix will continue streaming you video so long as you keep providing larger partially signed transactions every minute. After another minute, you send Netflix another partially signed transaction using the same funding transaction as the input. This new partially signed transaction would send .000002 Bitcoin to Netflix (to reflect the two minutes of watch time), and 9.999998 Bitcoin to you. You keep doing this every minute.

With unidirectional payment channels, there’s no possibility of cheating. If you stop sending Netflix partially signed transactions every minute for higher amounts each time, Netflix will stop streaming you video. They will sign the most recent partially signed transaction you sent them (which entitles them to the most Bitcoin), publish it, and thus close the channel.

Furthermore, there’s no risk of anyone publishing an “outdated” transaction. Netflix is the only one capable of spending any of the partially signed transactions (since Netflix has your signatures, but you don’t have any of theirs), and every newer partially signed transaction you send Netflix is strictly better for them than any older one. Netflix can only cheat itself by publishing an earlier transaction.

When money flows in both directions, this gets trickier. Both parties can publish transactions, so incentives exist to publish an outdated transaction.

The Problem with Bidirectional Channels

Say Alice and Bob open up a payment channel and each lock up .5 Bitcoin in the funding transaction. Now, Alice agrees to pay Bob .1 BTC for a carwash. She sends Bob a partially signed transaction that uses the funding transaction as its input with two outputs: one that sends .4 BTC to her, and one that sends .6 BTC for Bob.

By not publishing this transaction, Bob keeps their channel open. He later agrees to pay Alice .3 BTC for a painting.

If Bob sends Alice a partially signed transaction that uses the funding transaction as its input, they will each be in possession of a different, yet valid, spend of the same funding transaction. Transactions have no expiration date in Bitcoin, so their transactions will be valid forever.

It doesn’t matter if they keep sending partially signed transactions back and forth for other goods and services. Either of them can act maliciously by publishing any earlier transaction that entitled them to more Bitcoin, thereby closing the channel, and making all other signed transactions invalid.

Bidirectional channels need a way to invalidate outdated transactions so that only the most recent signed transaction can be used to close the channel. That’s where eltoo comes in.

eltoo

Bidirectional payment channels in the Lightning Network work out-of-the-box today because the whitepaper created a working protocol to invalidate outdated transactions. This protocol, named LN-Penalty, penalizes participants who try to publish outdated transactions by allowing the other party to steal the cheating party’s Bitcoin.

Though LN-Penalty works today, it has problems. Besides its complexity, edge cases exist where it risks accidentally penalizing an honest user. eltoo is not yet usable because it relies on a proposed signature scheme SIGHASH_NOINPUT which has yet to be adopted, but because it is not penalty-based, there’s no risk of losing your funds.

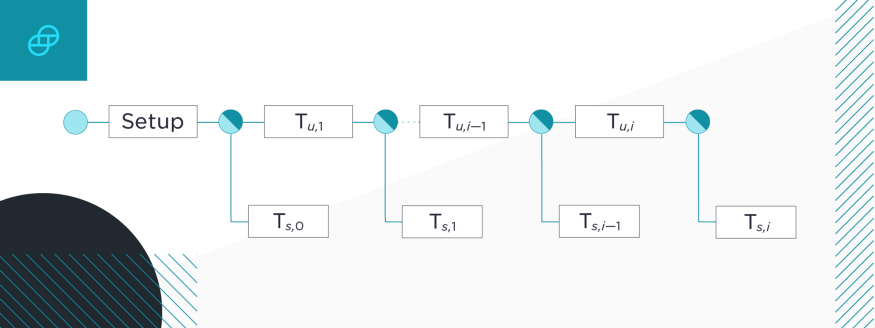

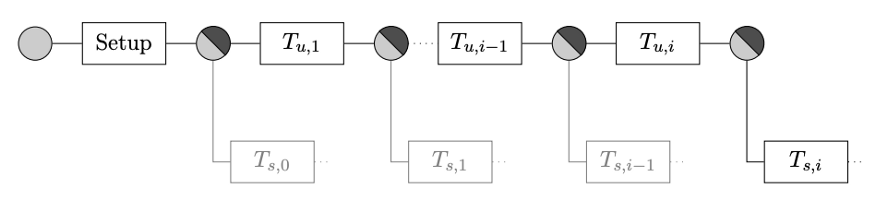

In eltoo, the two parties create the funding transaction denoted by Setup in the diagram below. The funding transaction could contain Bitcoin from both parties, because we anticipate money flowing in both directions.

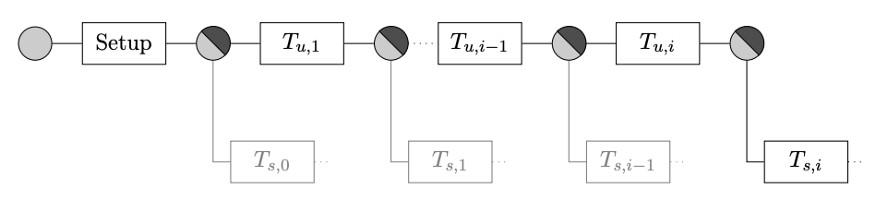

Each circle represents a transaction output. Diagram from the eltoo whitepaper.

Each circle represents a transaction output. Diagram from the eltoo whitepaper.

Before signing the funding transaction, Alice and Bob first sign a settlement transaction(Ts,0 in the above diagram) which refunds the Bitcoin in the funding transaction to each appropriate party. In eltoo, the term “settlement transaction” describes any transaction that distributes funds back to the participants, rather than to a multisig output that they both control.

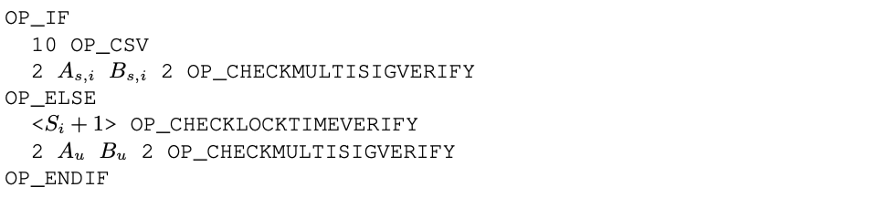

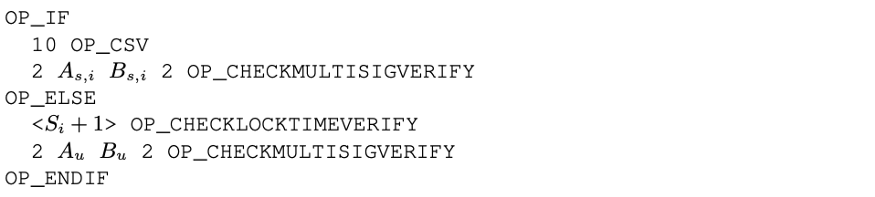

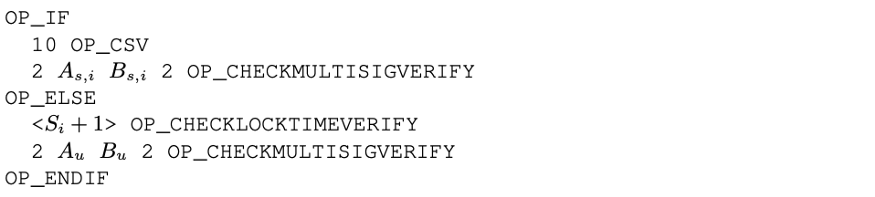

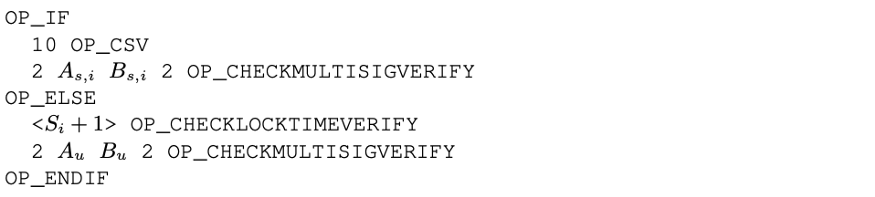

After they sign the first settlement transaction, the parties can safely sign the funding transaction. The locking script for the funding transaction looks as follows:

Locking script for the funding transaction, and any other update transaction. Image from the eltoo whitepaper.

Locking script for the funding transaction, and any other update transaction. Image from the eltoo whitepaper.

There are two ways to spend the funding transaction: one in the IF branch, and one in the ELSE branch. These two branches rely on two separate sets of keys: the IF_branch requires _settlement keys, and the ELSE branch requires update keys. The two parties, Alice and Bob, each control one key from both sets of keys.

You’ll notice that the settlement branch of this locking script contains 10 OP_CSV (short for OP_CHECKSEQUENCEVERIFY) as its first instruction. Any transaction attempting to spend this funding transaction by unlocking the IF branch can only do so if 10 blocks have passed from when the funding transaction entered the blockchain. If Alice and Bob exchanged signatures for the settlement transaction, then published the funding transaction to the Bitcoin blockchain, then published that settlement transaction, it would take 10 blocks before their settlement transaction could be mined to give them control of their respective funds.

Instead of publishing the settlement transaction, Alice and Bob keep the channel open. Say Alice wants to send 1 Bitcoin to Bob, so their new balances are 4 Bitcoin for Alice, and 6 Bitcoin for Bob.

The first thing Alice and Bob do is exchange signatures for a new settlement transaction. This new settlement transaction will pay 4 Bitcoin to an address only Alice controls, and 6 Bitcoin to an address only Bob controls.

Here’s the key point of eltoo: this new settlement transaction does not spend from the same funding transaction. Instead, it spends the output of a transaction Alice and Bob have yet to make: an update transaction.

An update transaction’s purpose is effectively to double-spend the funding transaction, so that the original settlement transaction (that Alice and Bob both signed, which had a block delay of 10 blocks), becomes unusable.

Recall the locking script of the funding transaction:

The locking script from the funding transaction

The locking script from the funding transaction

While the settlement branch has a 10 block delay, the update branch does not. If Alice and Bob ever exchanged signatures from their respective update keys, they could spend the funding transaction by unlocking its update branch well before the settlement transaction they signed ever could.

After Alice and Bob sign the new settlement transaction that sends 4 Bitcoin to Alice and 6 to Bob with their settlement keys, they exchange signatures from their update keys to create the update transaction. With that, the old settlement transaction that refunded their initial balances becomes irrelevant, and the new settlement transaction — which spends the update transaction — is the only one that can issue payouts.

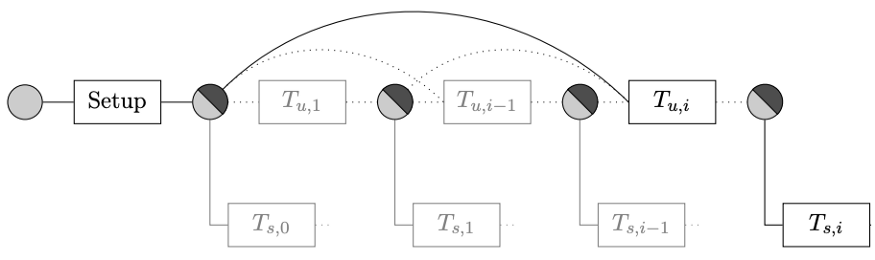

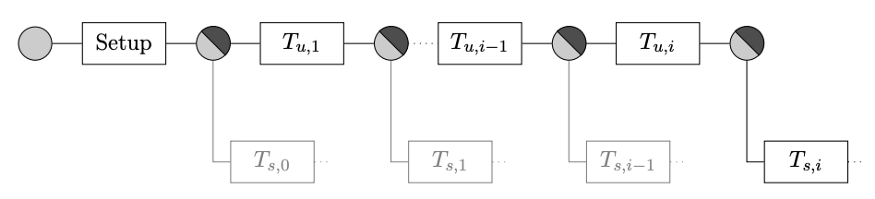

This process of creating update transactions and settlement transactions can continue like this indefinitely, as the image from earlier showed. The most recent settlement transaction Ts,iis the only one that matters, because Alice and Bob have signed a chain of immediately-publishable update transactions that guarantee none of the earlier settlement transactions could take effect.

Each circle represents a transaction output. Diagram from the eltoo whitepaper.

Each circle represents a transaction output. Diagram from the eltoo whitepaper.

You’ll notice that while this proposed model works, it requires every intermediary update transaction to be published on-chain. This defeats the purpose of the Lightning Network, which transacts off-chain to keep on-chain data light.

That’s where SIGHASH_NOINPUT comes in. Instead of having to publish the entire sequence of update transactions all the way to your most recent settlement transaction, SIGHASH_NOINPUT allows you to skip over all update transactions until the one you need.

SIGHASH_NOINPUT allows “binding” to any earlier transaction.

SIGHASH_NOINPUT allows “binding” to any earlier transaction.

Though an output’s locking script can dictate that a specific set of keys must provide a signature to spend it, it does not dictate what that signature must contain. Usually, you sign every input and output in your transaction, and inform Bitcoin nodes that you have done this by appending the SIGHASH_ALL flag next to your signature. This means that you are announcing to every Bitcoin node that your transaction should only be considered valid if the specific combination of inputs and outputs contained in your signature are present in your transaction. If any other combination — a different input, an output with a slightly different value, etc. — appeared than what you signed, you are telling Bitcoin nodes to consider your transaction invalid.

With SIGHASH_NOINPUT, you can instead create a “free floating” transaction. You are announcing to Bitcoin nodes examining your transaction that you don’t care what the input to your transaction is — you only care about the output. That means that your signature will be valid on any unspent output that required those specific keys to spend. You don’t care which unspent output you’re spending — you’re OK with spending any of them.

As in the diagram above, using the SIGHASH_NOINPUT flag allows us to bind the last update transaction to the funding transaction. The last update transaction has already been signed, and though it initially pointed its input to spend the update transaction just before it, we can change which unspent output it spends without making the signature invalid because we explicitly state that the input is not part of or relevant to our signatures. All other intermediate update transactions can safely be skipped.

Thus, only three transactions must be published by the end of the channel: the funding transaction, the last update transaction, and the last settlement transaction which distributes the final balances to each party by spending that last update transaction.

Issue with Ordering

You might notice that free floating update transactions present an issue. If the last update transaction can bind to to any earlier update transaction (including the funding transaction), then the opposite is true: any of the earlier update transactions can bind to the last update transaction as well. This would nullify the last settlement transaction!

To address this, eltoo cleverly invokes the concept of state numbers in its locking scripts. This maintains an ordering between update transactions, such that update transactions can bind backwards_indiscriminately, but not _forwards. Again, the locking script on any of our update transactions looks as follows:

The locking script from the funding transaction

The locking script from the funding transaction

The ELSE branch is for update transactions, and the first instruction is:

<Si + 1> OP_CHECKLOCKTIMEVERIFY [OP_CLTV for short]

OP_CLTV_in an unspent output checks the nLockTime of the transaction that attempts to spend it. When you submit a transaction with an nLockTime of over 500,000,000, Bitcoin interprets it as a Unix timestamp. That is, the spending transaction won’t be mined until that timestamp is met. Any value less than that is treated as a minimum block height; that is, your transaction can’t be mined until the Bitcoin blockchain is _this tall.

But there’s a clever trick here! If you make nLockTime greater than 0, less than 500,000,000, and less than the Bitcoin blockchain’s height, then any transaction you publish can be mined immediately. This defeats the purpose of using nLockTime to delay transactions from being mined, but we can use that entire range of values to create an ordering between our update transactions without arbitrarily delaying them from being mined.

Say the funding transaction specified an OP_CLTV_of 1. This means that the first update transaction, denoted by Tu,1, would need an nLockTime of at least 1, so Alice and Bob make sure the next update transaction has an nLockTime of 1. The output produced by the first update transaction would then specify an _OP_CLTV of 2 in its locking script. The next would specify 3, and so on.

Now, if Alice and Bob tried to bind the first update transaction to a later output — say, the third output — the Bitcoin blockchain would reject it, because the first update transaction’s nLockTime is 1, while the third output has a locking script requiring an nLockTime of at least 3.

Although all of the update transactions are signed with SIGHASH_NOINPUT, no earlier update transactions could bind to a later update transaction, because the nLockTime would be below the required OP_CLTV in that output’s locking script. This protects the integrity of the last settlement transaction, denoted Ts,i.

Settlement transactions must also use SIGHASH_NOINPUT . In the event the output it spends changes its input to point to the funding transaction (because the channel is closing), that output’s transaction ID would change, because the input of a transaction is part of what makes up a transaction ID. Thus, any settlement transaction needs to be able to change its input to reflect the new transaction ID without making its existing signature invalid.

However, you’ll notice the settlement branch of the locking script does not contain any concept of state numbers like the update branch does.

The locking script from the funding transaction, and any subsequent update transaction.

The locking script from the funding transaction, and any subsequent update transaction.

At first glance, it would seem this would cause the same problem we described earlier: old settlement transactions could be applied to future update transactions, producing a race condition to see which settlement transaction would be mined on-chain.

Instead of using state numbers, the solution here is that each settlement transaction uses a different keypair that gets derived from the state number of the output it spends. Thus, while the settlement transaction maintains the flexibility of changing the transaction ID in its input without invalidating its signature by using SIGHASH_NOINPUT, it can still only spend that specific output_because the keypair from its signature _only unlocks that specific update transaction. Thus, settlement transactions maintain a unique binding to a specific output by having a specific keypair that only works with that output.

Wrapping Up

Bidirectional state channels can be complex, but eltoo provides a simple, innovative way to implement them. I hope you enjoyed this view into the Lightning Network — stay tuned for similar posts!