Blockchain Is a Semantic Wasteland

Blockchain Is a Semantic Wasteland

Why haven’t we abandoned it?

By Nic Carter

Posted October 5, 2018

Credit: Bigmouse108/iStock/Getty Images Plus

“Blockchain” this, “blockchain” that. It’s a concept so momentous that it has even managed to shed its article. Proponents don’t speak of “the” blockchain or “a” blockchain. Instead, they reverently preach Blockchain: the solution to all enterprise needs (in particular, supply chain management). The brute, unassailable, self-evident concept has disrupted not only the rules of commerce but those of grammar. Question it and you’ll be exposed as a hopeless rube and a Luddite. Use it sincerely and you’ll be lumped in with the hype men and techno-utopians.

It’s impossible to avoid. Ads for IBM blare promises about revolutionizing tomato-tracking with blockchain. The U.K. finance minister recently asserted that blockchain may be a solution to Britain’s Brexit woes. At a recent conference held by Ripple, former U.S. President Bill Clinton said of blockchain, “the permutations and possibilities are staggeringly great.”

The word “blockchain” is satire-resistant. It’s such an obvious target that it’s no longer funny, and blockchain proponents are almost totally immune to ridicule. Nothing can check their indefatigable enthusiasm: There are press releases to be written, conferences to attend, and corporate R&D dollars to waste. Blockchain represents both the glittering future and the dismal present — almost all touted use cases are obvious nonsense.

The ICO mania of 2015–2017 that is now unwinding was premised, in large part, on the ability of blockchains to disrupt markets. In simpler terms, the idea was to Uber-ize every conceivable service and replace the intermediary with a magic database detailing who is doing favors for whom. Some of those pitches invoked trillion-dollar (yes, trillion with a T) total addressable markets.

Today’s soulless corporate blockchains and opportunistic, ICO-based blockchains have both endured scorn and ridicule. Yet the term persists, an empty semantic husk, kept alive by a thousand press releases, conveying as little meaning as possible. The term is used to refer simultaneously to projects, structures, and databases that have virtually nothing in common. As a consequence, attempts to define it are usually hopeless failures.

Here, I’ll try to explain the origin of “blockchain” and what we should do about it.

Where did “blockchain” come from, anyway?

Most histories of the term “blockchain” will mention that Satoshi Nakamoto created the first one. Except, that’s not accurate. Nakamoto never referred to bitcoin as a blockchain, calling it instead a “chain of hash-based proof-of-work,” a “chain of blocks,” and even a “timechain” (in an early comment within the original codebase). Imagine: We were so close to living in a world of “enterprise timechains” and “strawberries-on-the-timechain.”

Nakamoto was careful to emphasize that the chain was a set of proofs of work, each linked to the hash of its parent. (See for yourself!) The proof of work is absolutely essential to the concept. It is proof that anyone proposing a block has, well, worked for it. It enables the system to achieve Sybil resistance and to come to convergence (the longest chain — under the same ruleset — is the correct history, by definition) without any single arbitrator.

This data structure, with its inclusion of hashes of previous blocks, ensures that the past is preserved and the database is consistent. Replicating the database to every node in the network ensures that it can’t be shut down or altered unilaterally.

The reason “blockchain” is such seductive marketing… is the subtle implication that the data structure alone — absent proof of work or open validation — could convey the same benefits as bitcoin.

The entire system was built with an adversarial context in mind. Hostile governments had shut down all previous attempts at e-cash. They certainly would have shut down bitcoin if they could have. Thus, it was built for a purpose. To clarify: Nakamoto may have created the first popular, widely used linked-list structure — not the first of its kind — but the innovation was in merging that linked list with the computational hardness of adding new entries to the chain.

Does this sound like what any of the enterprise blockchains are trying to accomplish? Of course not. There is no shadowy organization dedicated to forging strawberry provenance records that might seek to interfere with IBM’s supply-chain blockchain. Thus, IBM’s blockchain does not need to be built to the same standard as bitcoin. The kinds of records preserved on enterprise blockchains do not need the kinds of protections that Nakamoto consensus ensures. They do not need or want open validator sets. Some trusted organization could just vouch for the database, or a consortium of interested parties could share records between them.

For more on the failures of private blockchains, I recommend this post from a reformed private blockchain consultant.

Why is the term so popular?

From what I can tell, people witnessed the success of bitcoin — which relies in part on an ersatz, expensive database — and wanted to generalize it to other uses. Even early bitcoin developer Hal Finney mused about disaggregating the data structure from the monetary system.

It also might be possible to refactor and restructure Bitcoin to separate out the key new idea, a decentralized, global, irreversible transaction database. Such a functionality might be useful for other purposes. Once it exists, using it to record monetary transfers would be a sort of side effet and might be harder to shut down. — Hal Finney in his January 24, 2009 Cryptography Mailing list

However, to the best of our knowledge, these systems only really work if the reward is internal — that is, if well-behaved validation is rewarded with the “native” token. If bitcoin miners were paid in U.S. dollars, they wouldn’t necessarily have any incentive to mine on top of the longest chain. The value of their hardware depends on the continuing existence and flourishing of the chain they’re building on top of. But private, permissioned, or enterprise blockchains do not have native currencies nor do they issue monetary units to validators, as the validator set is permissioned and thus has Sybil resistance and good behavior built in by design.

“Blockchain” is such seductive marketing, I believe, because the data structure alone — absent proof of work or open validation — could convey the same benefits as bitcoin without the token or costly anti-Sybil protection.

Patri Friedman put it well in a tweet:

Bitcoin is a monolith that colors the way investors and corporate R&D offices think about similar projects. Would Ripple have been as popular without bitcoin having been invented? What about Corda and Hyperledger? Litecoin? ICOs generally? Ethereum? It is hard to even imagine the alternate history, but I suspect the answer is no in all cases. Bitcoin is a juggernaut that carried with it a set of assumptions that were ported over to projects with a passing resemblance, rightly or wrongly.

Consequently, I would be suspicious of anyone who routinely uses “blockchain,” especially if they are trying to sell you something. Overuse of the term, especially in a general context and without qualifiers, most likely reveals one of three things about a person:

- They are well-meaning but forced by convention to use subpar linguistic tools.

- They are a bit muddled and trying to mask their ignorance with technobabble.

- They are trying to posture as an expert in an industry which realistically has no experts.

I firmly believe the misuse of the term traces back to a desire to create (or market) systems that are intended to be bitcoin-like without the unsavory bits. That, however, misses the point: Bitcoin’s blockchain is just a part of it, not its essence.

Bitcoin and its blockchain

Referring to bitcoin as a blockchain is like referring to a car as a transmission. A transmission is a key element of the system, but it doesn’t represent it in totality. Blockchain is a metonymy — a part used to refer to the whole. There’s nothing wrong with that, intrinsically. The conceptual tangle comes when one decides that the blockchain is bitcoin’s essence and is owed credit for its success.

Bitcoin relies on a linked list, indeed. But it also relies on a peer-to-peer (P2P) network, an open source and leaderless project, a replicated database, a self-supporting incentive system, a heaviest chain consensus rule, and a proof-of-work scheme that gives block proposals unforgeable costliness. (Unforgeable costliness in simple terms: It’s impossible to fake a block submission; you would have to have allocated a good chunk of computing power, or energy, to the task. It is therefore hard to create new bitcoins but easy for anyone to verify that you worked hard at it.)

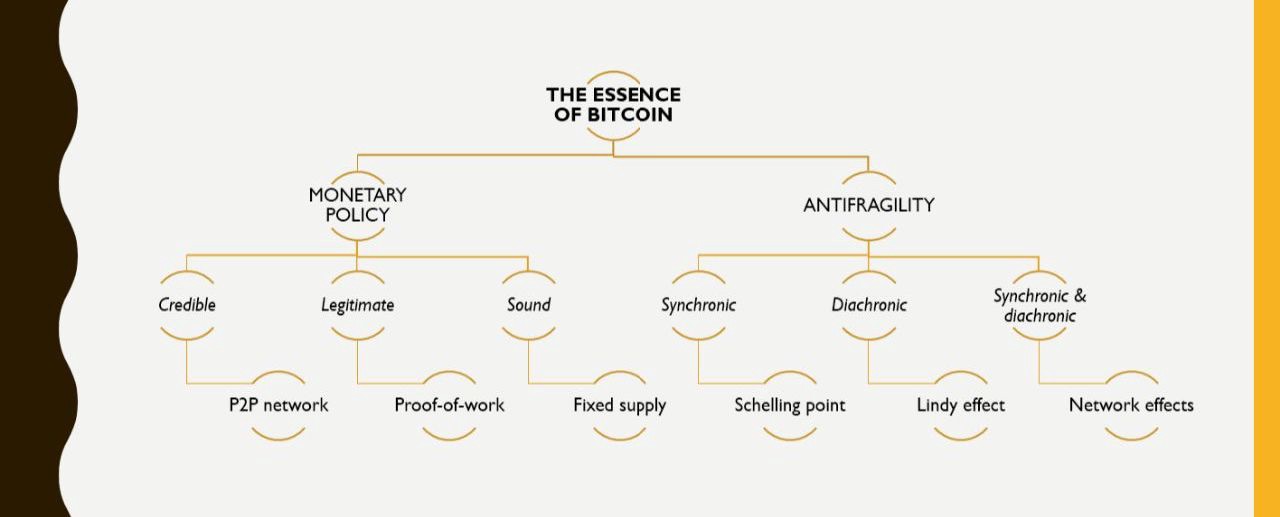

These inputs combine nicely to create a system that has certain qualities: provable scarcity, an ability to be audited, tamper-resistance, fair-ish distribution, almost perfect supply inelasticity (rising the price does not — cannot — cause production to accelerate), free participation (no one can stop you from broadcasting a bitcoin transaction), and so on. These qualities make bitcoin a unique relative to, say, Paypal or Visa. They are its differentiators. Without the P2P nature, the open-source collaboration, the voluntarist developers, and, crucially, the proof of work block proposal method, bitcoin would not exist. The below chart, created by David Puell based on ideas from Pierre Rochard, is an attempt to capture bitcoin’s essence. Notice that the chain of blocks, while necessary to make the system work, is not sufficient on its own. Bitcoin relies on more.

David Puell’s laudable attempt to characterize bitcoin’s essence in one chart.

David Puell’s laudable attempt to characterize bitcoin’s essence in one chart.

I can’t tell you exactly what the essence of bitcoin is, but to limit it to a chain of blocks is reductionist in the extreme. The soul of bitcoin is not the blockchain. But if you pull the blockchain out of bitcoin, you get something rather empty.

Why rail against “blockchain”?

I believe better conceptual frameworks will lead to better outcomes. Author George Orwell believed that the words we use directly affect the way we see the world. He even intimated that scrubbing words from popular usage could eliminate their referents, the very concepts they sought to represent:

The purpose of Newspeak was not only to provide a medium of expression for the world-view and mental habits proper to the devotees of IngSoc, but to make all other modes of thought impossible. It was intended that when Newspeak had been adopted once and for all and Oldspeak forgotten, a heretical thought — that is, a thought diverging from the principles of IngSoc — should be literally unthinkable, at least so far as thought is dependent on words.

Eliminate the word “freedom” from popular use and you’ll eliminate the desire for freedom entirely, so the theory goes. Additionally, Orwell strongly felt that sloppy language was indicative of muddled thought and used as a way to sneak indefensible assertions past an unwitting reader.

My point here is that in elevating the linked list to the exalted status of “blockchain,” we overrate it. In insinuating that bitcoin is just a blockchain or simply the origin of the more interesting underlying technology, we do bitcoin a disservice. By constructing the blockchain artifice in popular consciousness, we enable sloppiness of thought and do away with rigor. “Blockchain” dilutes the importance of a tremendously important and valuable innovation — a trust-minimized monetary system — and abases it by putting it to work to generate efficiencies, real or imagined, in enterprise supply chain management.

The path forward requires honesty

To the permissioned or enterprise blockchainers:Be honest about what you’re building. If you’re building a database controlled by a consortium of pre-permissioned entities, don’t claim or imply it will have similar reliability characteristics to systems designed to live in far more adversarial environments. Imagine how you would market your system had bitcoin not been invented.

Let public blockchains be. You aren’t competing with them. Your systems have totally different goals. If you do want to persist with the blockchain moniker, I encourage you to very carefully define what you mean by “blockchain,” and be sure to distinguish your system from open, public blockchains. Lastly, for god’s sake, give “blockchain” back its article (refer to “a” or “the” blockchain, please).

To the computer scientists:Stop mocking nontechnical people for using “blockchain.” You’re missing the point. They aren’t really referring to the data structure, so it’s beside the point to say, “Just use MySQL.” “Blockchain,” for better or for worse (definitely for worse) has become a term of art that is typically used to refer to the whole system — economic and social — rather than just the data structure.

To regulators:Please do not try to define “blockchain” or create blockchain regulation. You will fail, not due to your lack of astuteness but because the term “blockchain” is so semantically dispersed as to be undefinable. Definitions need to be specific and useful and also general enough to encompass all of the members of the set. However, these tensions tear “blockchain” apart. It is used too generally to be useful.

@prestonjbyrne Florida proposed my favorite definition of “blockchain”, which may or may not be pretty much everything or nothing. — -@zackvoell](https://twitter.com/zackvoell/)

Instead, disaggregate. Recognize that legislation covering cryptocurrency probably cannot cover security tokens, “utility tokens,” and permissioned blockchains too. Private or enterprise blockchains aren’t just “bitcoin in a suit” — they’re totally different. The two really have nothing in common.

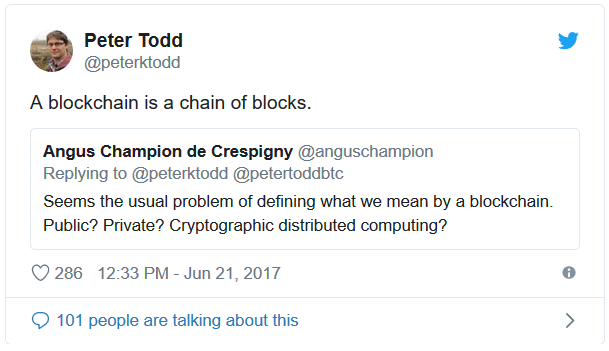

To everyone else:Please join me in spurning the use of “blockchain” at every opportunity. Let’s try and devise new terms that are specific enough to be useful and do justice to their referents. I currently use “public blockchain” to describe permissionless, open networks like bitcoin and Ethereum, but I would love to use a different term that doesn’t rely on the b-word. If you do insist on using it, I like Peter Todd’s definition best: “A blockchain is a chain of blocks.”

Using it in a minimalist, direct way removes some of its conceptual weight. This eliminates its ability to implicitly promise amazing consistency, reliability, and uptime. The more honest your definition of “blockchain,” the less it lends itself to exciting press releases. The blockchain, in Todd’s definition, is really just a way to arrange data. And that is supremely unsatisfying given how it’s used today.

If you want to read more about disaggregating these systems, I recommend Distributed Ledger Technology Systems: A Conceptual Framework, published by an interdisciplinary set of practitioners and academics under the aegis of the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance.

I believe that in five or 10 years, we will look back at the popularity of “blockchain” and be slightly embarrassed.

Canny readers will notice that I co-founded a firm that invests in blockchain startups. This is true. I am humiliated. But our use of the term is a matter of practical reality. The term has proliferated widely enough to become a Schelling point — an easy meeting place where technologists and allocators can communicate. Out of convenience, and so that we are understood, we use the term. But we’d love to abandon it. It encompasses many distinct concepts, some of which we love and some of which we hold in contempt.

I believe that in five or 10 years, we will look back at the popularity of “blockchain” and be slightly embarrassed. The term will seem as archaic as “surfing the world wide web” or using the “information superhighway.” Consider this an open solicitation for replacements to the term. Let’s move on.