BetterHash: Decentralizing Bitcoin Mining With New Hashing Protocols

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

BetterHash: Decentralizing Bitcoin Mining With New Hashing Protocols

An Overview Of Mining Pool Exploits That BetterHash Disables

By StopAndDecrypt

Posted July 14, 2019

Intro

BetterHash is the working name for alternative mining protocols currently in development. When it’s completed there will need to be enough miners willing to switch to a new mining pool using these protocols, or an existing pool that is willing to service both the old and new protocols while miners gradually ready themselves to switch over. In either circumstance the initial switch will need to be supported by enough miners to make doing so profitable, else profit volatility would be too high. Ultimately miners will need to understand why they should switch, and there will need to be forward thinking pool operators who don’t want the control current pools have. This can only happen if the problems and risks with the current system are properly understood and conveyed.

Disclaimer: This is not a fork, or a consensus rule change.

So what exactly is wrong with Bitcoin mining now?

Bitcoin mining has a representation problem. Bitcoin mining pools are not Bitcoin miners, yet pools unduly signal for them. Pools run the node, construct the block, select the transactions, and can choose what fork all of their miner’s hashpower is used for. This creates a handful of incentive issues and enables some pretty undesirable political leverage. BetterHash aims to address this by giving those responsibilities back to the individual miners, and stripping the mining pools of their influence for the greater good of the network. With BetterHash miners would control their own hashpower, and pools would just coordinate them and distribute the rewards.

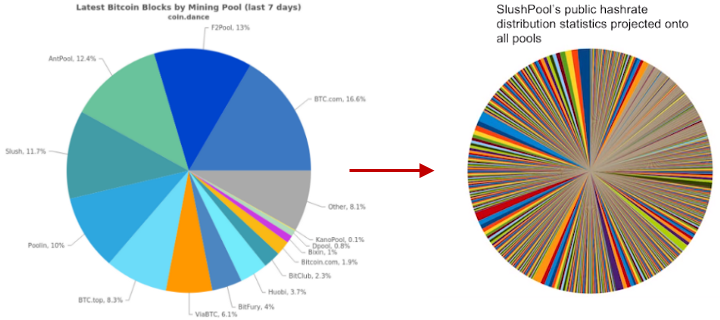

Mining pool hashpower distribution, versus Slush Pool’s miner distribution projected onto every pool.

Mining pool hashpower distribution, versus Slush Pool’s miner distribution projected onto every pool.

This article aims to highlight the kinds of exploitation pools can conduct under the current mining environment — of which would not be possible if BetterHash-like protocols were adopted — at the expense of what may be the miner’s best interests. Pools can also be hacked and then used by the attacker to engage in this behavior. Before we get to that let’s briefly go over the structural differences between what exists now and what BetterHash protocols would change about it.

Currently, many miners don’t even run nodes and simply connect their ASICs to a mining pool using protocols like Stratum. The pool runs the node, selects the transactions, creates a block they would like mined, and then sends that block out to all of the miners using their pool and the miners begin hashing it. Once a miner successfully mines a block, it gets sent back to the pool and out to the Bitcoin network.

With BetterHash, miners will individually run their own nodes, select the transactions, create a block, and then mine it. The block would be configured to pay the pool, and just like with the Stratum protocol, those unsuccessful blocks (called “shares”) would be used by the miners to prove they’ve been mining for that pool the whole time.

By just changing who creates the block template to be mined to the individual miners, instead of the pool owner, and then building a new protocol around that concept, BetterHash circumvents all the issues we’re going to cover.

For a more technical overview on the BetterHash protocols currently in development, this presentation by Matt Corallo should suffice, but is not necessary to understand the exploits this article discusses because conceptually BetterHash is objectively better, and a fully codified implementation doesn’t need to exist in order to grasp how important this is.

It should be noted that the name “BetterHash” is not definitive, as mentioned in the video.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0lGO5I74qJM

The Status Quo

To understand why switching to BetterHash is so important, let’s unpack all the problems associated with the way things are now for miners that wouldn’t exist if they were using BetterHash.

To be brief, mining on your own has returns that are most likely too volatile, which is why pools have existed since as early as 2010. Critics will point at pool distributions to claim Bitcoin mining is centralized, and while counterarguments assert miners can just switch the pool they use, it’s not always that simple. If you’re a miner your options are limited to a handful of mining pools, each with their own terms of service that you may or may not agree with. Pools are too large to provide a diverse set of options to pick from.

At the end of the day you have no choice but to choose the pool best suited to you, and if most or all of the pools decide that some practice you don’t like or agree with is going to be the norm, then you have no real alternative but to deal with that, since starting your own pool probably won’t produce a steady enough income stream. Pools that already exist are relatively large, and by having many miners under each of their umbrellas, pools have the power over their miner’s hashpower to do a number of questionable things that we’ll go over one by one.

Pools can:

- Determine what transactions do or don’t go into a block

- Be bribed to reorganize the blockchain under the right conditions

- Backlog transaction mempools to inflate the fee rate

- Direct hashpower without consent & mine competitive forks

- Dishonestly mine, should they have ulterior motives for doing so

- Signal support for a proposal using a miner’s hashpower

All of these issues are essentially the direct result of pools building the Bitcoin blocks instead of the miners, as mentioned earlier. Along with pool exploitation comes third-party exploitation of the pools. Pools can be hacked and then the hackers can potentially conduct these exploits, or pools can be attacked from a network level and then miners are left scrambling to figure things out or switch to another pool. With BetterHash a pool hack wouldn’t be able to control a miner’s hashpower, and network level attacks targeting a pool wouldn’t have a direct effect on the miners using that pool.

Network level attacks are just as concerning if not more than pools exploiting their miner’s hashpower. An attacker can bring down a large chunk of the hashpower or redirect it as they please. BGP attacks are easy to do and the time & resources required to recover from them is concerning, to say the least. To convey how trivially an attacker can steal a pool’s hashrate and conduct any of the exploits written in this article, watch 3 minutes of this presentation below:

https://youtu.be/k_z-FBAil6k?t=353— Network level attacks discussed at the 5:52 mark, ends at 9:00.

There’s no doubting the benefits of a protocol that defends against these kinds of issues, but solutions to often unheard of potentialities don’t always do a great job on their own conveying their necessity. I’d like to bring to light some hypothetical scenarios as well as some that have already occurred in some fashion, so that necessity is more readily understood. So let’s take a closer look at what each of them are. (Please note that some of these are hypothetical and unlikely to actually occur, and some require very specific circumstances, while others have occurred in one form or another already.)

1: Pools determine what transactions go into a block

Often an issue raised when discussing the possibility of 51% attacks, if enough pools can be convinced to blacklist a transaction type or an address, even temporarily , then it doesn’t matter if you — a miner — personally don’t care and would have included it. The motivation for this could be coercion or just a financial incentive to do so, whether the pool’s own, or a external one paid to the pool.

Scenario #1: Censoring a service’s hot-wallet

Imagine an exchange’s hot wallet being blacklisted by 40% of the pools, paid for by a competing exchange? It wouldn’t bar that wallet from transacting indefinitely, but it would noticeably slow down their transaction processing. As a miner, maybe you don’t think that behavior is healthy for the ecosystem, but maybe you just have no other choice since you have no say in what your pool does in secret.

Scenario #2: Censoring confidential transaction types

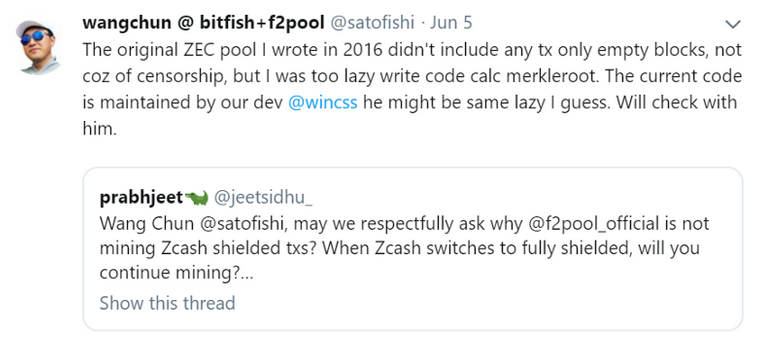

“Maybe the developer was the same kind of lazy”, resulting in code that ignored shielded transactions.

“Maybe the developer was the same kind of lazy”, resulting in code that ignored shielded transactions.

The tweet above ended up proving — if we trust his word — this example to be non-malicious, but it’s still important to consider scenarios in which something like this was done intentionally. Bitcoin doesn’t have confidential transactions at the moment — and may never have them — but it does have different transaction types. If a pool had a reason for doing so, then they could theoretically ignore them so a backlog of specific kinds of transactions exacerbates, raising fees and potentially slowing down any service that makes use of those specific of transactions.

2: Pools can be bribed to reorganize the blockchain

Similar to the examples above, pools can decide they don’t want a specific version of a transaction to be included in the ledger, and then try and act on this decision. Such a scenario would be next to impossible to coordinate spontaneously, or in hindsight, but if pools were so inclined then just a few of them could build software in preparation for a bribe, and then act on it immediately without miners having any say in the matter.

Miners might believe this is in their best interest if the bribe was shared with them, but pools have less of an incentive to do this the higher a share they give to the miners. Additionally, in a hacking scenario the hacker could counter the bribe to the pool, muddying the waters even more.

This was a suggestion after the exchange Binance was hacked — although the pools weren’t prepared for it — and many used this to make arguments about Bitcoin mining being centralized, when in reality it’s just the pools that have too much leverage over miners that this could even be potentially abused. For more nuance on this subject, give the podcast below a listen and make note that none of the things being discussed in it would matter if BetterHash was being used, because this would have been impossible to even consider if miners built the blocks instead of pools.

3: Pools can backlog transactions to inflate the fee rate

Not only can pools bar specific transactions, they can choose to ignore all transactions below a specific fee rate, raising the costs for everyone trying to transact. Some consider this a trivial issue because smaller pools will take the opportunity to include those transactions since the reward for them is greater, rewarding the underdogs in the long-term. I don’t think it’s as trivial as this, since we’ve seen how the effects of this behavior can steer arguments in the political arena over rising fees in the short-term.

Sooner or later a fee market is going to exist, but throttling the network below its consensus enforced limitations shouldn’t be a tool granted to a handful of people running pools. While competition may exist at the pool level to counter this behavior, we continue to see empty blocks mined by select pools because the financial incentives are aligned, along with instances in the past where a few specific pools only had transactions that were above 5 satoshis/byte, even when there was room for the remainder of the transactions in the backlog. It might require some coordination among pools to have an effect, but if the incentives align then that coordination isn’t difficult or even necessary, and now a small group of pool operators would have a valuable tool at their disposal that nobody else has.

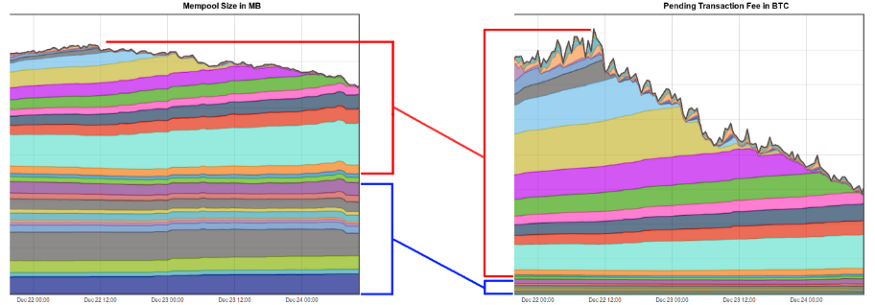

Pools can also do this covertly. Instead of creating “non-full” blocks, they can fill them with what looks like legitimate but unannounced transactions that they then collect back to themselves, to throw off people, businesses, and fee estimators by leading them to believe the new “going fee rate” is real. Once the market starts paying the higher price then pools could just adjust their malicious transactions up again. At the time of the image below, the bottom 50% of the TX backlog in sizeaccounted for only ~ 7% of the reward miners collected in fees. The reward grew non-linearly with the median fee rate in the transaction backlog, making this a lucrative endeavor for any large enough pool wanting to try this out.

https://www.reddit.com/r/Bitcoin/comments/7lwajx/spamming_the_network_unfortunately_doesnt_result/

https://www.reddit.com/r/Bitcoin/comments/7lwajx/spamming_the_network_unfortunately_doesnt_result/

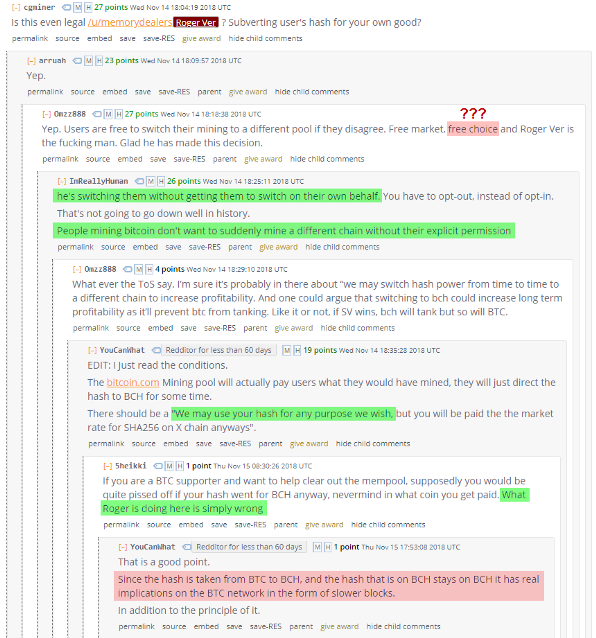

4: Pools can direct hashpower without consent

In more ways than one, pools choose what chain to extend. Pools feed the miners a block and effectively just say “mine this block”, the miners mine that block until it’s found by someone, then pools feed them the next block. Miners aren’t tracking different branches themselves, and miners generally assume that the pool is being honest and mining the coin/fork you expect them to mine. Many miners aren’t running nodes, so they aren’t validating the consensus rules. This has caused problems in the past when pools decided that they were also not going to validate blocks, but instead “SPV mine” on top of invalid blocks. As a miner you should want to know that your time and money isn’t being wasted by the pool you’re using.

A scenario:

You’re a miner, and you’re part of Pool_A. You receive a steady stream of payments for the amount of hashpower you provide to the pool. You’ve done the math, it checks out, and that never changes.

The operator of Pool_A decides they are going to use your hashpower to provide “life support” for another chain that’s at risk. One that you don’t care about and possibly dislike or consider to be competition. The pool continues to pay you “the market rate” for your SHA256 rigs, but your hashpower isn’t actually being used on the chain you think you’re mining.

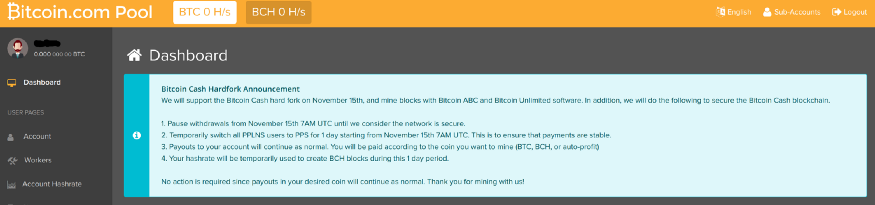

Since there’s now an entire pool mining a different chain, the network’s block production rate slows down — decreasing rewards — and the market is potentially fooled into thinking there’s more support than there actually is for another chain — decreasing the potential value of your chain. As a miner, this is probably a scenario you would want to avoid. Unfortunately, this scenario has already happened in real life:

https://www.reddit.com/r/btc/comments/9y5qpj/roger_ver_calvin_if_you_happen_to_watch_this/e9yj4fy/?context=10000 https://www.reddit.com/r/btc/comments/9x2ekv/all_poolbitcoincom_hashrate_to_mine_abc_chain_for/e9ozqes/

5: Pools can dishonestly mine using miner’s hashpower

Consider the scenario above to be the best case example of how this would play out: The pool is being honest with the miners about their intentions, and they are at least attempting to remedy what they think will be the financial burden. They’re giving the miners a heads up, and telling them if they don’t like it then leave — which is not always simple. But what if they were dishonest?

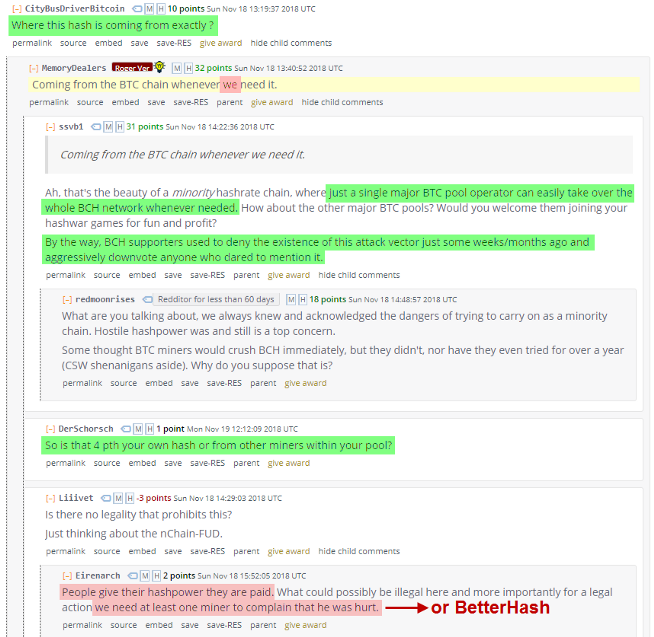

Allocated Hashpower is what a pool signals to the world, but not necessarily what miners intended to mine.

Allocated Hashpower is what a pool signals to the world, but not necessarily what miners intended to mine.

If a pool showed_they were mining two chains, Yellow & Green at 80% & 20% respectively, and you were mining the Green chain through them, how would you know they were being honest that only 20% of their miners supported that chain? They could individually tell each miner that _they are the 20% and they’re the only ones supporting it, when they really aren’t. Miners would have to coordinate on side channels and add up their hashpower to figure out if they’re being deceived. The main issue with that is many miners are private, and many want to remain private, will remain private, and should remain private. Coordinating like this is an impractical workaround to avoid being deceived and manipulated.

Not only would this sort of lie allow complete exploitation of all of the miner’s combined hashpower, but the disinformation could influence the market’s valuation of each chain. Anyone who values the long-term health of the Bitcoin network would want to avoid these kind of scenarios.

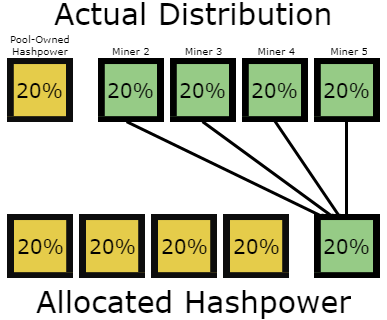

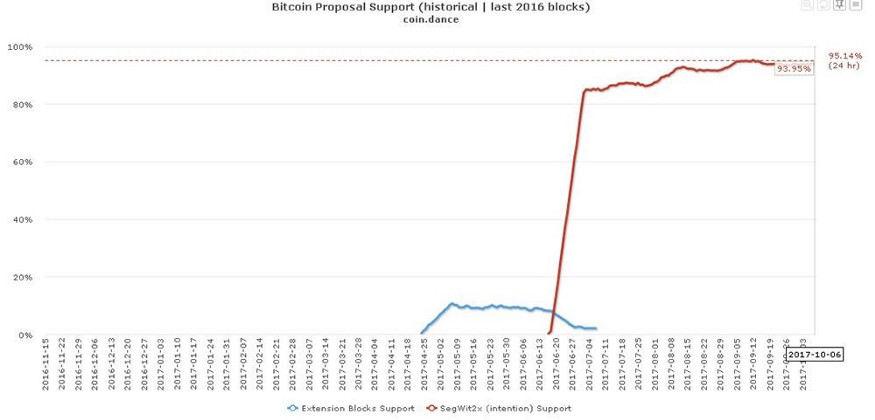

6: Pools can signal for a proposal using your hashpower

There doesn’t even need to be an actual chain-split for this kind of manipulation to take place. Since the pool gets to signal for all the hashpower under their umbrella prior to an actual fork, a situation like the one below would give the appearance that 80% of the hashpower is signaling for or against some proposal or fork. Given that signaling isn’t a financial commitment, there’s little risk involved in doing so. You would only need to persuade the few individuals running these pools to temporarily signal support if you wanted to try and move the market in your desired direction. If it fails — like we witnessed with NO2X — then it’s at no loss to the mining pools. Everyone’s hashpower still works regardless of the result.

Each column represents a pool. The top section of each column represents hashpower owned by that pool, while the bottom section is meant to represent the variety of other miners that use the pool.

Each column represents a pool. The top section of each column represents hashpower owned by that pool, while the bottom section is meant to represent the variety of other miners that use the pool.

No one knows exactly what percentage of hashpower all of the pools actually own versus how much belong to other miners using a pool, but the extra transparency is without a doubt a bonus for the — effectively — silent majority of the hashpower without a voice. Nobody wants another NO2X scenario, nor should a handful of pools be able to “decide” that the majority support something when they really don’t. Perhaps the NO2X movement wouldn’t have been necessary if BetterHash existed a few years ago.

Miners didn’t signal for Segwit2X, mining pools did.

Miners didn’t signal for Segwit2X, mining pools did.

Conclusion: Perspective Matters

I anticipate there being two different common reactions from people upon reading this, both of which I’ve already received from a handful of people reviewing it. I think it’s important to highlight this for the reader — you — and address it.

- “I didn’t know mining pools have so much power.”

- “This can give the appearance that pools have more control than they really do.”

Now for the “meta-considerations”, at first glance one might think:

“The first person probably didn’t know much about mining or Bitcoin in general, and the second person has been around the block and understands the nuances enough to measure these scenarios more appropriately.”

Another way one might view this would be:

“The first person is providing a fresh and real perspective on learning about the balances of power in this system, while the second person has been around for a while and has gotten too comfortable and desensitized to the way things are and the potential threats.”

Both of those initial reactions are valid. Both of these meta-considerations are valid. If pools had no potential to abuse the system the way it’s currently set up than there would be no drive to develop better protocols, and you wouldn’t be reading this. Conversely, if pools were such a significant threat to Bitcoin than they would have abused their power in irreparably damaging ways by now (see BCash ).

Alternatively to these polarizing perspectives, this is what I’d like your takeaway to be instead:

BetterHash needs to be implemented, because BetterHash is objectively better than what we have now. Pool abuse and network attacks shouldn’t be possible, and we can alleviate these concerns by simply getting miners to run their own nodes so they can create their own blocks, and using a better pooling protocol structured around that simple but fundamental change. There’s always the potential that something could go seriously wrong if we don’t get ahead of a problem that we know how to fix, so let’s fix it.

Additional Resources

Bob McElrath: Decentralized Mining Pools for Bitcoin

Off Chain with Jimmy Song : How Mining Pools Work with Matt Corallo

What Bitcoin Did: Matt Corallo on How Bitcoin Works