A Fossil Fuel Future for Bitcoin Mining

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |

A Fossil Fuel Future for Bitcoin Mining

By Maximilian Fiege

Posted October 22, 2019

This is an adaptation of a report originally written for clients of Signum Global Advisors alongside Angela Dalton, Managing Partner for Technology.

The launch of Application-Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs) for Bitcoin mining 2013 set off a modern day gold rush. In the six years since, miners have scoured the globe in search of cheap electricity to power the commercial-scale operations made possible by such special purpose hardware. Their scramble has raised eyebrows along the way, with headlines decrying Proof-of-Work as some deal with the devil in the age of climate consciousness. This past year, however, miners found their work vindicated by research indicating that three-fourths of all mining draws on marginal renewable electricity at little expense to surrounding communities. This should bring an end to the energy debate once and for all, no?

Not quite. Because while we had the good fortune of Bitcoin emerging during a peculiar period of energy abundance, we are not likely to see these conditions continue on in perpetuity. And rather than assume that certain supply gluts will remain, we should instead take a proactive approach in forecasting how growing demand for renewable energy, and tumbling fossil fuel asset prices, will create new ones.

The Subsidization of Proof-of-Work

Consider the following thought experiment: what if the Oil Shock of 2007 had precipitated a near-decade of economic malaise like the OPEC crisis of 1973 had done? As you suspend your disbelief, you might ponder how the emergence of ASIC mining in 2013 would have played out. A perfect storm of high energy costs and utilities’ conservation policies would impact miner willingness to contribute computing power. The constrained hashrate affords weaker network security, and low government tolerance for consumption would also attract greater scrutiny. It remains unclear to what degree a Proof-of-Work network could scale in a period of energy scarcity.

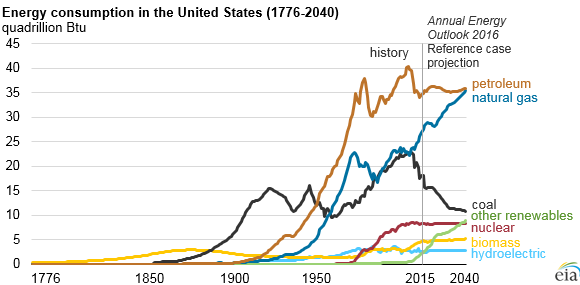

Now let us return to the real world, in which Satoshi released the Bitcoin source code on the eve of an energy sector expansion unlike anything seen since the Oil Boom a century prior. In particular, 2009 marked the intersection of three trends that have defined the energy market of the past decade:

- The culmination of a two decades-long buildout of Chinese hydropower

- The middle of America’s transformation into a net exporter of natural gas

- The beginning of solar power carving out product-market fit worldwide

The ramifications of these trends are myriad, but of relevance to Bitcoin mining is the glacial pace at which grid operators have responded to this changing power generation landscape. The challenges posed by integrating the intermittent energy produced by renewable sources has left them scrambling to scale up energy balancing, transmission, and storage capabilities accordingly. This phenomenon is reflected in curtailment rates, which express how much of total generation capacity had to be shut off or grounded to avoid frying the grid. The result: regional supply gluts ripe for Bitcoin miners to draw from, all without ruffling the feathers of what should be one of their natural predators, the government-sanctioned utility.

The difference between how our counterfactual and reality played out suggests that our understanding of Bitcoin is too forward-facing. We often picture Bitcoin as locked in an existential struggle with central banks, but the network managed to achieve unicorn status with little sovereign resistance. In understanding how Bitcoin passed a twelve-figure market capitalization, it makes more sense to think of central banks as the proverbial final boss, and to recognize that utilities have had far more opportunity to strangle this grand experiment in its cradle. We can see this empirically: governments worldwide have intervened against miners, whereas running a node or holding a wallet is only “outlawed” in a motley crew of jurisdictions (e.g. Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Nepal).

We are forced to accept the conclusion that the availability of cheap energy has played a role in the success of Bitcoin to date. The design of the network allowed for certain regions with excess energy to subsidize a global settlement platform without ever attracting the ire of any entity capable of torpedoing the whole experiment. As bureaucratic inefficiencies allowed miners to exploit these supply gluts in peace, network hashrate has grown to a point where now a peeved utility or government agency would struggle to marshal the resources necessary to attack the network. Indeed, network hashrate has grown ~100x since September 2013 and a multi-day 51% attack would now cost some billions of dollars. But what happens when these gluts are gluts no longer?

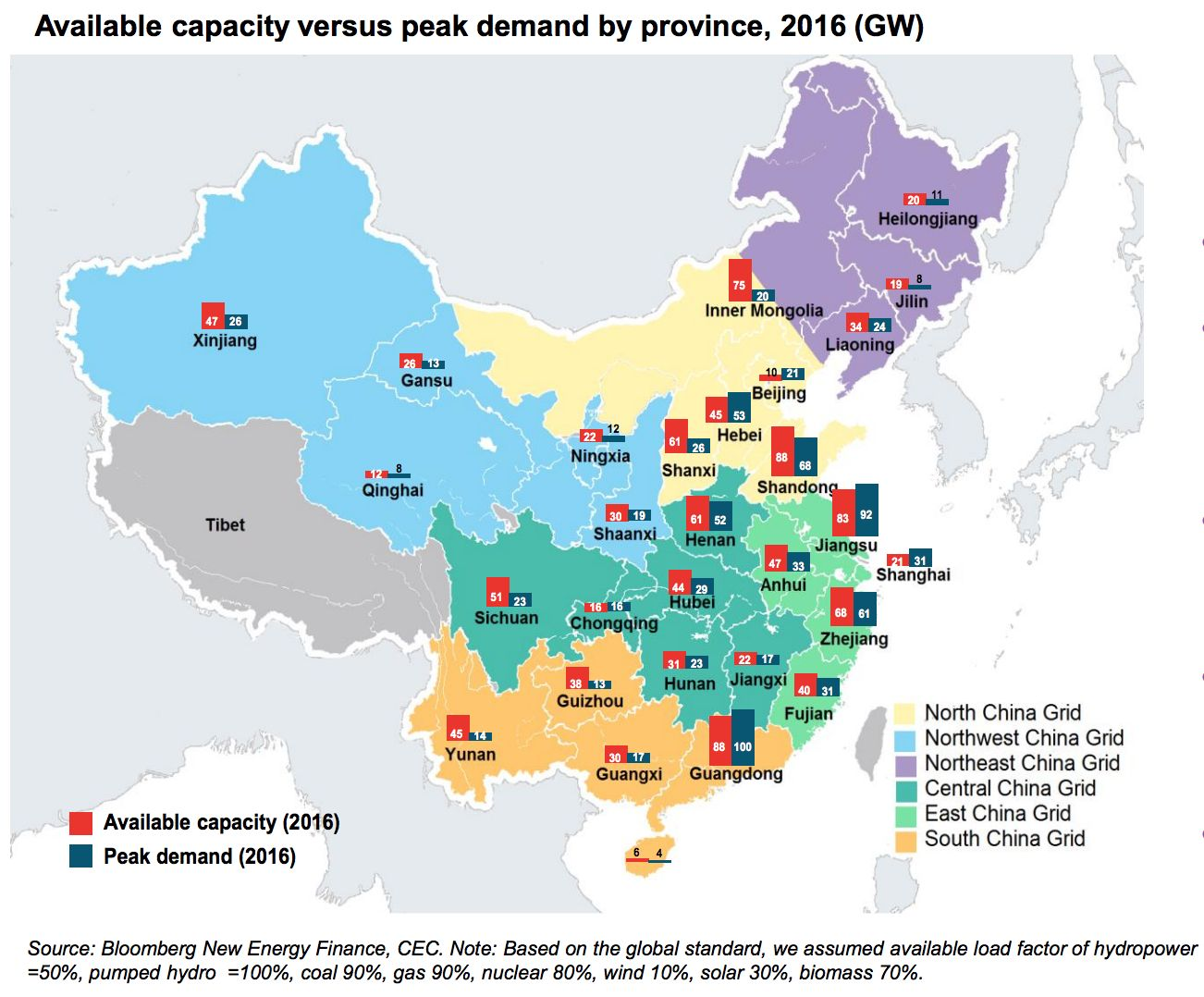

Curbing Curtailment

Renewable energy curtailment has served as the key tailwind behind the rise of Bitcoin. It occurs when an asset like a wind farm or a dam produces an excess amount of energy relative to demand at a given time, forcing the grid operator to reduce or divert output in order to preserve the integrity of the power system. In the regions that have attracted miners, we can chalk this excess up to geographic remoteness — areas like Sichuan, Inner Mongolia, and Alberta have low population densities relative to the sheer amount of power being generated. As a result, local energy prices remained depressed relative to the rest of country and miners can operate with little worry for utility throttling. Leading Bitcoin researchers harp on this phenomenon to argue that the future of mining will remain with “stranded” renewable energy assets, even more so than it has in the past:

- “Bitcoin miners are highly mobile and can therefore serve as cornerstone demand for low-cost stranded renewables.”

- “It’s the stressor that will force our archaic carbon-based energy system to adapt.”

- “Bitcoin will spur innovation in the development of renewable energy technology & resources.”

This sentiment, however, underestimates the technological progress being made on transmission and storage methods in response to the evolving demand profile for these renewable assets. It is an error to assume that curtailment is inherent to renewable energy; that governments and financiers would simply accept terawatt hours-worth of wasted renewable energy when climate change is their most pressing political issue. Indeed, for political and technical reasons, the availability of marginal renewable energy for mining will decrease over time, challenging the current model of private mining operations.

Parallel Political Pressures

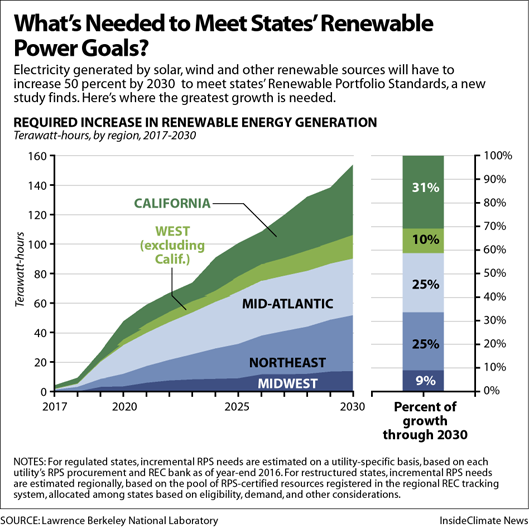

Developed economies are staring down the double barrel of their millennial constituencies’ chief demand: decarbonize and electrify as much energy consumption as possible. Whereas government intervention to date has focused on propping up renewable energy via subsidies and federal R&D, the next stage will require diminishing demand for fossil fuels. And while solar and wind are already out-competing carbon incumbents under certain conditions, outright bans or onerous taxation schemes on the latter will lead to massive increases in demand for the former. Take California, for instance: alone to have a 100% renewable energy-powered EV fleet by 2045 would require a 500% increase in current renewable generation capacity.

Whether driven by the Green New Deal in the US or the 13th Five Year Plan in China, the political zeitgeist of the coming decade is going to result in a scramble for renewable energy. In the immediate future, that will require tactical deployment of existing renewable assets — we’re starting to see crackdowns on inefficient use already. And don’t forget that current outlays for renewable energy R&D are not on par with prior decades’, raising doubts about the feasibility of deep decarbonization past 2030. These realities are already setting in for traditional businesses: Daimler is discontinuing further internal combustion engine development, Stripe has committed to negative emissions, and so on. As more and more of the physical economy piles into renewable energy assets, miners looking to continue their curtailment arbitrage can expect to find themselves labeled as persona non grata sooner rather than later.

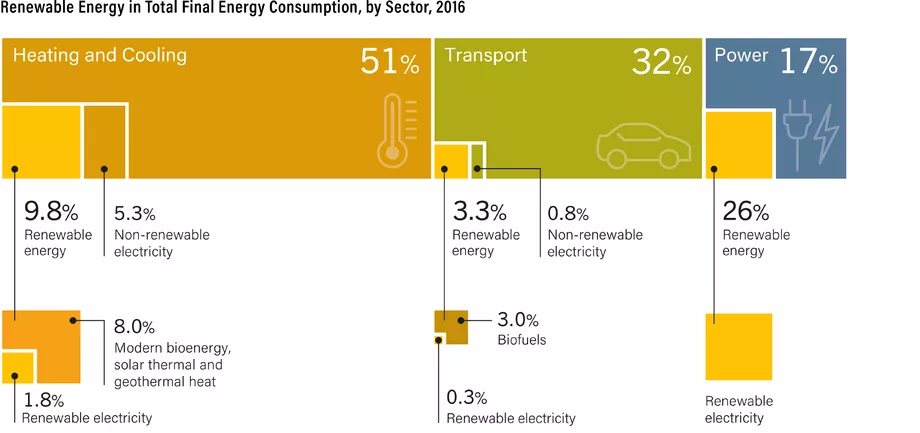

David Roberts, “The global transition to clean energy, explained in 12 charts”, Vox

David Roberts, “The global transition to clean energy, explained in 12 charts”, Vox

No Renewable Left Behind

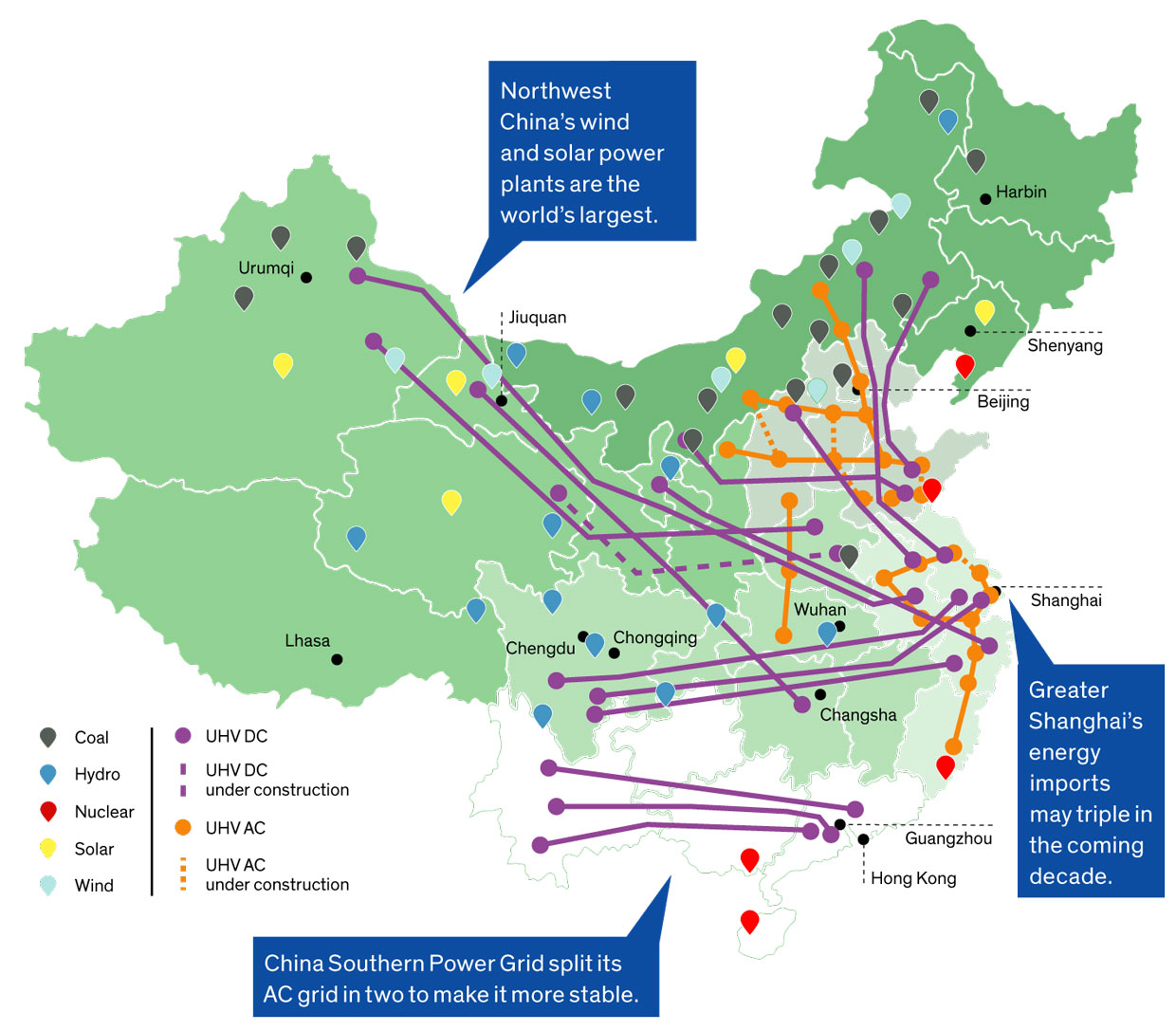

But are these political promises backed by actual solutions? The aforementioned Bitcoin analyses stress that geographically-stranded renewable assets, like the majority of the dams that power mining today, are beyond the reach of a realistic grid integration strategy. That may have been the case earlier in the decade, but the tide is turning. Technological progress on grid-level storage and ultra high voltage DC transmission, as well as organizational improvements on inter-regional coordination, promise to reduce curtailment rates and smooth out electricity costs. Most relevant to the miner status quo are:

-

Ultra-High Voltage Transmission: China has laid over 30,000 kilometers-worth of high voltage transmission lines, which allow for minimal energy loss over long distances, to date. The State Grid Corporation’s deployment of a 1,100-kv (ultra-high voltage) line stretching over 3,000 km between Xinjiang and the greater Shanghai region in January of this year helped drop the region’s wind curtailment over 15% year-on-year. While the State Grid has struggled to make full use of its world-leading transmission infrastructure in the past, top brass in Beijing is making it clear that regional grid squabbles will not sideline national goals. Given that China represents 60% of Bitcoin hashrate, projects like the Wudongde DC line between Yunnan and Hong Kong indicate how these efforts will raise electricity costs in key Bitcoin mining hubs.

Erik Vrielink, “China’s Ambitious Plan to Build the World’s Largest Supergrid”, _IEEE Spectrum_

Erik Vrielink, “China’s Ambitious Plan to Build the World’s Largest Supergrid”, _IEEE Spectrum_ -

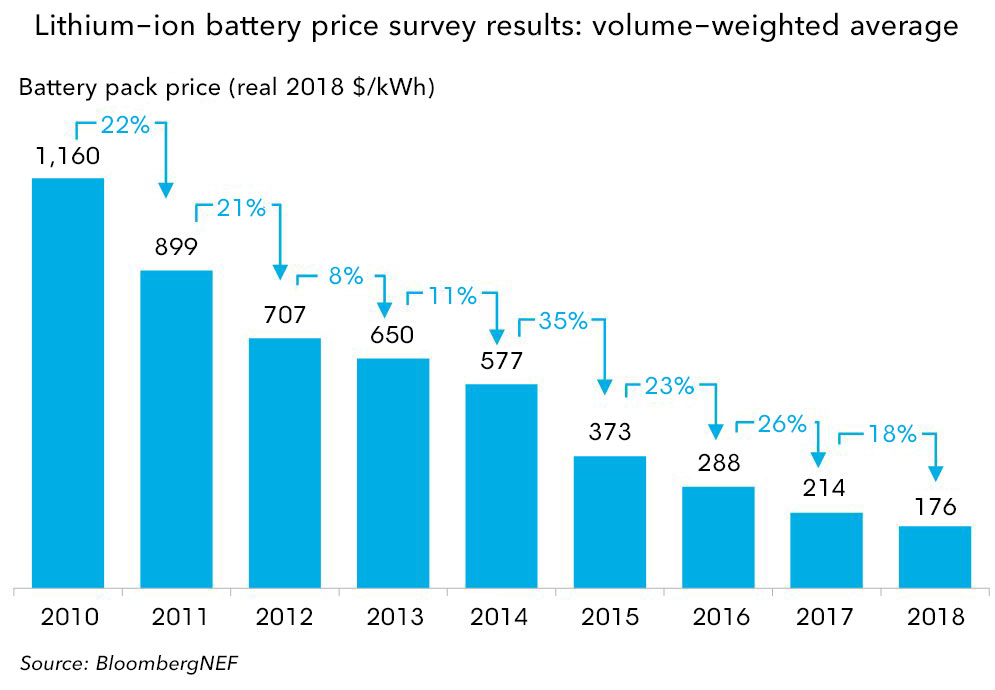

Grid-Level Storage: We find ourselves on the precipice of a golden age for, well, big batteries. The per-kWh cost for lithium-ion has dropped seven-fold since 2010 and is closing in on the $150/kWh target necessary for wind and solar to be competitive in 95% of US grid applications. With eight 100 MW-capacity storage projects going live by 2021 in the US alone, utilities appear intent on storage serving as their primary curtailment solution. And let us not forget alternative storage solutions: China has earmarked over 18 gigawatts-worth of new pumped storage hydropower by 2023, and long-term sulfur aqueous flow batteries could hit the market by 2025. Current grid storage solutions can already reduce curtailment by up to 38% and we should expect extensive deployment and further progression along the learning curve to result in even greater reduction rates.

Bitcoin miners have relied on the geographic arbitrage of renewable energy assets to power their operations. Because a watt of power generated among remote rapids was priced relative to local villagers’ demand for it (i.e. non-existent), miners benefited from cheap rates and indifferent utilities. Miners will see this strategy fall to the wayside as long-distance transmission and short-term storage reprice remote renewable electricity in terms of the utility it offers to metropolitan areas in need of clean power. That is to say, grid operators’ newfound ability to maximize the system-wide economic welfare of their respective networks will result in price normalization at the expense of higher-than-equilibrium rates in these formerly glutted areas. With less marginal electricity available, and it coming at a higher price, miners will need to find new competitive advantages to stay afloat.

Bitcoin Does Not Incentivize Renewable Energy

Before addressing the logical alternative energy strategy miners will pursue, let us dismiss the one they will not: building out renewable energy assets themselves.

The issue undermining this argument is the lack of common ground between the three relevant stakeholders involved: municipalities, financiers, and the miners themselves. Because miners are effectively energy nomads, or “buyers of last resort,” their preferred time horizon and tolerance for volatility fails to align with those of the former. They will pack up their things the moment local energy rates fail to provide a competitive edge, nor can they promise a predictable cash flow. For the multi-decade considerations of communities and infrastructure investors, these caveats reduce the idea of subsidizing new energy generation with mining to a nonstarter. Given miners’ need for flexibility, any strategy that saddles them with the long-term obligations of greenfield development should be roundly discarded.

And in the case of existing renewable energy assets, cost-benefit analyses will tend to favor better grid integration over leasing mining equipment as a curtailment reduction strategy. Moreover, the second order effects of rerouting that renewable energy to denser regions present a compelling ROI on building out transmission and storage infrastructure instead. Evidence from the US points to every kilowatt-hour of coal replaced saving $0.0436 in public health costs, as well as renewable energy infrastructure proving more resilient and creating more jobs relative to fossil fuel operations. For a grid operator tasked with promoting greater economic welfare within its region (read: all of them), the marginal return on integration far outweighs the benefits of any mining scheme.

To recap: countries are making it a priority to shift their energy consumption to renewable sources. Their voracious demand will result in a no-tolerance policy toward energy curtailment, and they will place an emphasis on grid-wide price levelization. This erases the electricity cost arbitrage miners have traditionally relied on for three-quarters of the Bitcoin hashrate, especially in Chinese hydropower hubs. This combination of relatively elevated prices and low tolerance for non-essential consumption amounts to politically-manufactured energy scarcity that will force miners away from their traditional haunts. Not wanting to anchor themselves with illiquid capital outlays, they will need to find existing energy sources they can repurpose at low cost and with minimal risk of utility intervention.

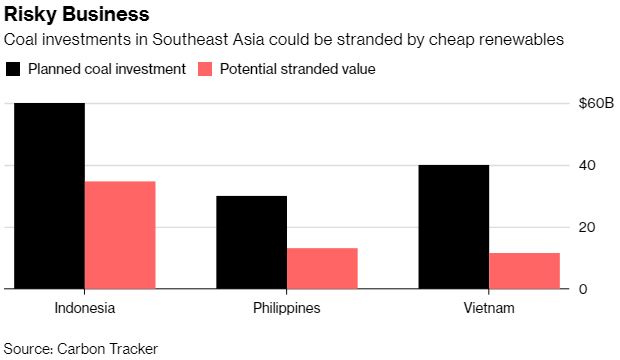

A Moment, Minsky?

For these reasons, Bitcoin miners will have strong incentives to align their operations with fossil fuels. As more and more fossil fuel assets become stranded due to declining profitability upstream and a lack of demand downstream, miners will emerge as buyers of last resort in the impending fire sale. Their primary draw will lie in unfettered access to wholesale energy prices that fall outside of the purview of utilities. Compared to the free lunch that has been billions of dollars-worth of cheap hydropower, the $5 trillion in potentially stranded fossil fuel assets represents a veritable 10-course meal, on the house.

Three key verticals offer the most compelling opportunities for miners:

- Coal in General: Current estimates peg global coal plant capacity peaking in 2021, due largely in part to cratering capacity factors and vanishing investment. The power plants and mines left behind provide little utility, and repurposing efforts require hundreds of millions in new investment that few countries can afford. In regions where market forces shuttered the coal industry, miners stand to purchase their own power generation, complete with transportation infrastructure, for cents on the dollar.

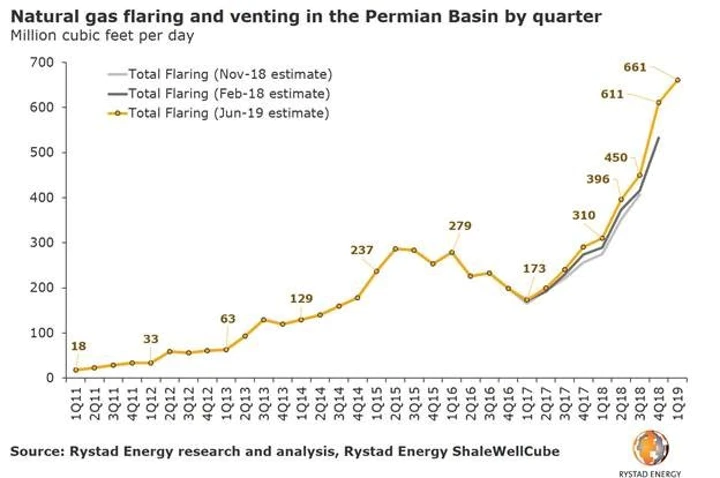

- Natural Gas in the US: American natural gas production has been on tear since 2005, growing total annual production by 50% since then and having turned the country into a net exporter in 2018. With close to eight decades-worth of recoverable resources left, the boom appears far from over. Plus, as continued tensions in the Middle East drive demand for American petroleum, the practice of natural gas flaring represents a curtailment-style opportunity for miners — the equivalent of 190 GWh was flared daily in Q1 2019 in the Permian Basin alone. Unsurprisingly, natural gas has sold at below-zero prices often in the past year.

- Sanctioned Countries’ Reserves: Coinshares attributed the ~3% drop in the exposure of Bitcoin hashrate to renewable energy between its November ’18 and June ’19 mining reports in part to Chinese miners moving to Iran. Couple that with the recent news that the Venezuelan central bank is considering to hold Bitcoin as a reserve asset, it is becoming apparent that mining offers a valid strategy for state actors looking to subvert American sanctions. With the value proposition of Bitcoin sitting at the intersection of finance and energy, it provides a silver bullet solution for countries that find themselves banned from exporting fossil fuels or trading in dollars.

Savvy miners are already recognizing this trend. Big Horn Datapower Holdings closed on a 107 MW coal plant in Hardin, Montana in March of this year; Bitmain has gone back and forth with Rockdale, Texas over the purchase of a former coal-powered Alcoa plant. Further phone conversations with local officials revealed miner interest in the opportunities of off-grid mining via coal and natural gas across Texas and North Dakota. Companies like Crusoe Energy Systems and Upstream Data have recognized the impending demand for these services, just as Bitfury has with its partnerships in the coal-rich northern regions of Kazakhstan. The prospect of utility independence and wholesale rates make fossil fuels far more compelling than grid-restricted renewables, and varying policy stances on them will allow miners to continue their whack-a-mole game of geographic arbitrage.

But at what point should we expect to see this tipping point in the Bitcoin hashrate energy mix? For the penetration rate to drop further, from ~74% to <50%, would require ~1.25 GW of the current energy draw, or 10 TWh of annual consumption, to switch over to fossil fuels. To put that in perspective: 2 months of redirected flaring in the USA could accomplish that. Even something as banal as the imposition of renewable energy quotas across Chinese provinces next year could eventually tip the scales. So, Steve’s point below presents a compelling argument.

CEO of Upstream Data

CEO of Upstream Data

The speed at which these developments will occur depends on a number of factors ranging from domestic Chinese policy to global geopolitical trends. Regardless, the writing is on the wall. Miners have spent the past six years profiting off of energy market inefficiencies, and they will continue to do so as fossil fuel prices fall through the floor. Analysts sell a false vision when they forecast that miners will enjoy bountiful renewable energy given that a) there is not enough for society’s existing needs, b) miners have no incentive to invest long-term in new generation, and c) utilities represent a natural competitor.

Concluding Thoughts

The future of Bitcoin mining forces us to consider what tradeoffs we are willing to make for the continued growth of the network. Mining blocks in a world with mass Bitcoin adoption will require orders of magnitude more energy than present. There is nothing inherently immoral about that, but it does present a challenge in the pursuit of a multi-trillion dollar market capitalization. With societal demand for solar, wind, and hydropower pushing out miners, the remaining options — private operations running on fossil fuels or state-sponsored operations with colorful characters — all put geopolitics front and center.

Choose your adventure: register your addresses with the IRS and OFAC to avoid tainted coins from Belarusian, Venezuelan, or Iranian miners; or find a new exchange because EU politicians banned an asset powered by American natural gas and Kazakh coal. No matter your acceptance of climate change, sanctioned countries and fossil fuel actors extending their shelf lives with mining revenues will bring renewed scrutiny to the network.

Author of “The Bitcoin Standard”

Author of “The Bitcoin Standard”

Should the proverbial honey badger give a damn? We can look to the Blockstream Satellite for a helpful analogy. The satellite exists in recognition of the fact that the reliance of Bitcoin on the internet represents a political vulnerability when considering ISP censorship or sovereign digital autarky. Likewise, miners must take a more proactive approach in assessing not just the wholesale cost of the electricity they consume, but also the price of the political risk they take on when choosing an energy source. That might seem counterintuitive for those of us who have come to understand mining strategy purely through the lens of operating expenses. But with close to 90% of all bitcoins already mined, it would make sense for existing miners’ electricity price sensitivity to decrease over time as their focus shifts from accumulating to preserving their BTC-denominated wealth. And if that’s the case, these coming energy market trends could very well be what sets off a medium-term transition from private mining (where cheap energy comes from fossil fuels) to state-partnered mining (where sustainable energy comes from on-grid renewable assets).

Special thanks to Ryan Gentry, Francis Corvino, Justin Leroux, Brandon Quittem, Owen Gwilliam, and Teddy Ogilvie-Thompson for their motivation and feedback over the course of researching and writing this piece.

Editor’s Note: This article originally led by giving credit to Avalon specifically for launching the ASIC mining boom. This has since been revised to just refer to the boom itself, without crediting any specific ASIC manufacturer.

| Crypto Words has moved! The project has migrated to a new domain. All future development will be at WORDS. | Go to WORDS |